Update

The Black Belt Needs More Than $1,200 to Survive COVID-19

05. 28. 2020

People deserve big, lasting direct payments that recognize the hardships rural black Americans, have faced for decades.

This op-ed originally appeared in Spotlight on Poverty and Opportunity.

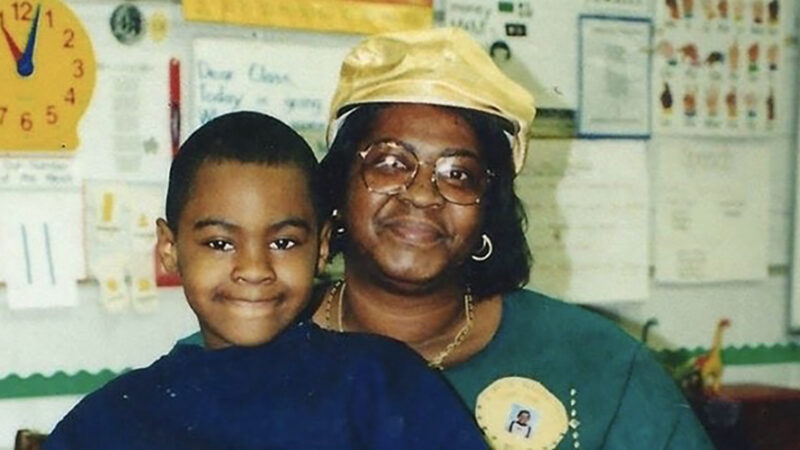

As coronavirus stimulus checks begin to reach Americans, I am well aware of the limitations of these one-time payments and the essential need for monthly $2,000 checks during the COVID-19 crisis. A lifelong resident of Barnwell, S.C., my grandma, the late Linda Joyce Hallingquest, spent her life trying to escape the entrenched poverty that plagues the nation’s Black Belt. After bouncing between local manufacturing plants because of layoffs, she lost her job at the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory in Aiken, S.C. after state budget cuts.

Years of working physically demanding jobs and being exposed to contamination from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) superfund site across the street from her home left my grandma with serious health needs. After spending 18 months fighting to get Social Security Disability Insurance, those $1,100 checks were barely enough to cover her monthly bills, especially once her health issues required more doctor visits and expensive medications. Often, my grandma had to rely on family or predatory payday loans to make ends meet. When she passed away in March 2016 at the age of 61, my grandma had less than $4,000 in total savings and owed more than $12,000 on her home.

Now, most residents of Barnwell have received or will be receiving a $1,200 check from the federal CARES Act. But like my late grandma, they also will continue to face economic hardship despite the one-time cash infusion. As with much of the rural South, Barnwell has grappled with an economic crisis that began well before the Great Recession. With the plant closures and state budget cuts of the early to mid-2000s, Barnwell lost the good-paying, family-sustaining jobs of the past, and unemployment jumped to record highs, peaking at 12.4% in December 2006. The closure of nearly every manufacturing plant has left Barnwell struggling with high rates of unemployment and poverty for nearly two decades, driving the city and county’s population decline as people are forced to leave in search of work.

Even amidst last year’s record-breaking stock values and low unemployment rates, Barnwell continued to struggle with high poverty rates, like much of the South’s Black Belt — the majority black counties that stretch from Louisiana up into southern Virginia. While the national poverty rate prior to the COVID-19 pandemic hovered close to 12%, poverty in Barnwell County was almost double at 22.4%. In a county of roughly 20,000 people, more than 5,000 people are Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients. The data shows black people are among the most affected, bearing the brunt of the economic instability plaguing this region of South Carolina. Black people face much higher poverty rates, with poverty among Barnwell’s black population at 36% compared to 17% for the white population.

For many in Barnwell, the $1,200 stimulus checks will never go far enough as COVID-19 continues to exacerbate long standing economic inequality. As with many across America, the check was spent before it was received, with many planning to use the money to catch up on bills and pay down debt. And for many, once the money is spent on necessities and outstanding bills, it’s gone. There is no money left to spend on the increased food expenses due to school and college closures or any additional medical costs. No money to ensure children have access to high-speed internet or other resources vital for remote learning. After spending their one-time check on bills, many in Barnwell and across the country will find themselves back at square one, with some facing even more dire circumstances as COVID-19 dries up Barnwell’s struggling economy.

While the CARES Act included important unemployment insurance expansions, South Carolina’s complicated and inefficient unemployment system will leave many in Barnwell without benefits, making them more reliant on their stimulus check. Since early March, more than 200,000 initial unemployment claims have been filed in South Carolina, straining the Department of Employment and Workforce, which lacks enough agents to handle the flood of applications and calls. Those who are able to draw unemployment are limited to a maximum state benefit of $326 — roughly $8 an hour to replace a 40-hour workweek. Some of these recipients will soon need to find a new form of relief as Gov. Henry McMasters’s efforts to reopen the economy will likely make them ineligible for continued unemployment benefits.

When debating the details of the next stimulus package, it is paramount that Congress keeps places like Barnwell in mind. People deserve big, lasting direct payments that recognize how COVID-19’s economic crisis only adds to the economic insecurity many, particularly rural black Americans, have faced for decades. Direct payments of $2,000 a month with automatic triggers tied to economic conditions, in combination with economic interventions like rent and mortgage suspension, will give Americans the necessary support for the current economic crisis while also setting the stage to improve millions of lives once the public health crisis is over.