The Affordability Framework

10. 21. 2025

The dual drivers of the affordability crisis explain the disconnect between strong macro economic indicators and the pain people feel.

This report introduces a two-part framework, identifying 1) broken markets and 2) broken incomes as dual drivers of the affordability crisis. This framework assesses the forces driving up costs for Americans and is intended to equip policymakers with a diagnostic tool to better understand these dynamics and inform future policy decisions.

Read the report summary

Visit link (opens in new tab):Read the fact sheet

Visit link (opens in new tab):| Broken Markets Three systemic failures make life unaffordable: | |

| Reason | What It Costs You |

| Gatekeepers Corporate power and weak governance constrain supply and increase prices. | Corporate concentration costs households $5,000 a year. Restrictive zoning slows economic growth, costing workers approximately $3,700 in lost income each year. |

| Fragmented Markets Market constraints prevent providers from scaling goods to the level needed to meet public demand. | Administrative bloat in the private health system wastes $528 billion a year. Rural hospital closures raise remaining nearby medical facilities’ prices by 3.6%. |

| Manipulated Signals Prices fail to reflect true costs and benefits because sellers obscure information, forcing others to pay more. | RealPage’s AI pricing algorithms increased impacted rents by $70/month. One estimate has future households paying an extra $70/month on their electricity bills to power AI data centers. |

| Broken Incomes Even when markets work, essentials remain unaffordable for three reasons: | |

| Reason | What It Costs You |

| Life‑cycle Mismatches Big costs arrive when earnings are low, in early career or when we are incapable of working. | A year of full-time child care for just one child ranges from $6,868 to $28,356. Without Social Security, 37% of seniors would be living in poverty. |

| Inequality Insufficient incomes and the high cost of being poor makes affordability worse. | Median wages have risen just 29% since 1979, while productivity rose 83%. Low-income families are forced to spend more hours navigating systems, paying a time tax. |

| Macroeconomic Trends Recessions have long-lasting consequences on people’s lives, and an inflation shock eats up wage gains. | New housing construction collapsed during the Great Recession, took eight years to only partially recover. Graduating into a recession decreases earnings for 10 to 15 years. |

Introduction

The affordability crisis is everywhere. People feel the pinch in grocery aisles, rental applications, daycare waitlists, medical costs, monthly broadband, and energy bills. Headlines announce strong economic growth, yet for millions of families, the essentials remain stubbornly out of reach.

Americans face skyrocketing prices in nearly every market they rely on for basic needs. In 2023, the median household income was $80,610. From 1967 to 2022, the cost of basic necessities—groceries, rent, health care, transportation, child care—increased 35% faster than everything else. Notably, the cost of groceries shot up by 23.6% from 2020 to 2024. The median home price has risen by an astounding 50% over the last five years alone—with the monthly mortgage cost increasing from $1,960 in 2023 to $2,035 in 2024. Rent is at an all-time high, with 50% of renters spending more than a third of their income on housing.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, the annual price for full-day child care for just one child ranges from $6,868 to $28,356, with huge variation depending on which state or city you are living in. For child care to be considered affordable based on a benchmark established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, it must not exceed 7% of a family’s household income. To afford full-day child care for just one child by this measure, households would need to make $98,114 to $405,085 annually, depending on where they live.

This year, Congress passed an enormous tax package, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), which will deepen this crisis and move families further away from baseline affordability and economic security. Health insurance premiums are set to skyrocket by as much as 500% or more in some states. Households will spend $170 more each year on energy costs by 2035. People taking on student debt to graduate from college will typically pay over $3,000 more per year.

“This Affordability Framework is a roadmap for understanding how policy failures and the decisions of public institutions have eroded pathways to upward mobility for millions of people”

The affordability crisis deepens existing faultlines in our economy based on geography, class, race, gender, disability, and immigration status. Some communities will bear the brunt of these rising costs more than others: the $1 trillion cuts to Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act, and Medicare will disproportionately leave low-income communities, people with disabilities, communities of color, rural communities, expecting parents, low wage earners, seniors, and refugees and asylees without access to health care. Slashing lifesaving social safety net programs like Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) will make it harder for many of these communities to afford the high cost of groceries. Reducing Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Social Services Block Grant (SSBG), and the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) programs will mean that close to 40,000 children across the country lose access to child care. These policy choices drive up costs for families and widen historic systemic divides entrenched in our economy.

The cost of living has gone so high, it kinda offsets everything I do to bring money in.

— Resident of Venice, IL

The persistently high cost of basic goods and services is not the only factor driving the affordability crisis. Decades of corporate consolidation and weak governance have given a handful of companies the power to rig markets to their benefit. As a result, consumers are left with fewer options, and suppliers are burdened by arbitrary constraints and emboldened to abuse pricing power. A rollback of government capacity and over-reliance on private markets to solve public problems has created incentives for providers to avoid scaling goods to the levels needed to meet public demand, contributing to limited options and rising costs for consumers, and worsening geographic inequality. This hits people the hardest when they are experiencing a shift in their financial situation, like moving to a new job, facing an unexpected medical crisis or juggling the new responsibility of caring for an aging relative or new child.

A Framework for an Affordable Future

This report introduces a two-part framework: broken markets and broken incomes, that identifies the dual core drivers of the modern affordability crisis. The goal of this framework is to thoroughly assess the forces driving up costs for Americans and equip policymakers with a diagnostic tool to better understand these dynamics and inform future policy solutions.

If you don't give people stability, how could you ever expect them to find upward mobility?

— Resident of San Jose, CA

There are key reasons markets remain broken, from gatekeepers that are incentivized to limit broader market access to those same actors manipulating supply and demand through predatory pricing strategies. But no matter how well markets function, income and opportunities must keep pace with the rising costs of essentials. If incomes stay stagnant or broken, essentials will remain out of reach, continuing to make life unaffordable for millions. Whether it’s widening inequality for impacted communities or the fact that most people’s paychecks simply do not line up with rising costs, fixing markets alone won’t be enough for Americans to thrive.

By examining the root causes of high prices and the rising cost-of-living, we can better understand the disconnect between macroeconomic indicators (like low unemployment, strong GDP, and cooling inflation) that point to a fundamentally strong economy, and the economic anxiety and pain that people feel today. Pessimism about the economy is at an all-time high, and the majority of Americans feel that the American dream no longer holds true. Public trust in government is near historic lows, with 78% of voters craving real change that improves Americans’ lives. This Affordability Framework is a roadmap for understanding how policy failures and the decisions of public institutions have eroded pathways to upward mobility for millions of people and stifled working families’ access to resources, opportunities, and power, keeping them trapped in economic precarity.

This initial framework deliberately does not issue policy recommendations specific to a market or industry, nor does it pinpoint just one cause of unaffordability. Instead, it broadly considers historical context, existing theories, and evidence, as well as people’s firsthand accounts of their own experiences, to animate why affordability has gotten further out of reach.

The second phase of this work will apply this framework to inform policy recommendations specific to the key markets contributing to the affordability crisis. These policy recommendations will build on the theory of the case laid out in this framework and incorporate perspectives and experiences from the people and families on the frontlines of the affordability crisis.

Our hope is this new framework is additive to the current political discourse. Much of the recent discussion of affordability tends to be sector-specific, offering analysis for why a singular sector, like housing or health care, has become expensive. Others analyze a specific tool or policy intervention that aims to address a broken system. This, too, is important and critical work, but when the analyses remain siloed by market sector or singular policy tools, it’s easy to overlook commonalities contributing to unaffordability across the board. This overarching framework aims to incorporate the best thinking, ideas, and learnings from experts across industries and sectors to better inform a set of downstream policy recommendations.

To give one such example, consider the recent interest in “Abundance,” the framework put forward by the writers Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson in their best-selling book. Abundance as an idea has roots in the Yes In My Back Yard (YIMBY) movement for more housing across the country; as one sympathetic commentator described it, Abundance is “a way to apply certain conceptual tools from the YIMBY movement to various non-housing policy domains.” It focuses on removing government-imposed bottlenecks and streamlining administrative processes to expand supply in the economy.

Abundance has important lessons for fixing the housing market specifically and land-use more generally. However, when applied to different sectors, Abundance has failed to account for important problems in federal rulemaking, as clearly exemplified in articulating the delays in rural broadband rollout. Indeed, some of the most important theorists of Abundance think this diagnosis can be too focused on federal capacity when in actuality this approach is most effective when applied at the state and local level. At the core, their analysis over indexes on government impediments to supply, failing to address structural market failures. By failing to include an analysis of how incomes become broken, Abundance as a framework cannot fully account for broken markets like child care and health care, and as such, will be limited in what it can explain and ultimately address. By contrast, this Affordability Framework includes the supply approach emphasized in Abundance while also incorporating that market failures, inequality, and lack of social insurance are equally compelling and important solutions to our affordability challenges.

Other academics are actively working on affordability that addresses both the markets and income sides of the issue. A recent report by economists Jared Bernstein and Neale Mahoney describes a “three-legged stool” approach to affordability: (1) enhancing supply, (2) providing direct subsidies, and (3) enacting competition policy. Like the Affordability Framework put forward here, they note that “taking down inefficient and friction-inducing barriers will not fully ease affordability constraints,” while also noting the nature of broken markets. As affordability arguments continue to evolve in different schools of thought, we expect to see an increasing number of economists and policymakers incorporate analyses of both broken incomes and markets as equal drivers of the cost-of-living crisis.

To tackle affordability, we must first unpack how economic structures break markets and disrupt families’ economic security. This is the Affordability Framework.

Why Are Things Unaffordable?

Broken MarketsDriver 1: Broken Markets

Too many Americans cannot access basic necessities because the markets that should deliver them are broken, unable or unwilling to produce enough to meet society’s needs. There are three key reasons for this: 1) private and public gatekeepers, 2) fragmented markets, and 3) manipulated signals.

GatekeepersReason 1: Gatekeepers

Both private and public actors act as gatekeepers across our economy, controlling the flow of goods and services families need to survive, thereby narrowing access to resources, power, and opportunities. By “gatekeeping,” we refer to not just the range of practices stemming from the dominance of a particular company or firm, but also how weak regulatory structures shape markets, constricting the supply of goods and services and increasing prices. This is not just the private sector. Wealthy homeowners and corporations can and do use the public sector to curtail investment and reduce supply below levels that most benefit society, especially when it comes to housing.

These dynamics amplify each other and significantly increase costs for consumers. Take housing, for example. Strict zoning laws limit the availability of housing, making too few homes that cost too much. At the same time, a significant increase in market power means powerful corporations have been able to raise prices far above their costs. The economist Thomas Philippon finds that, compared to the more competitive Europe, market concentration in the U.S. has led to higher markups and prices alongside weaker overall investment, costing American households on average an additional $5,000 annually across the economy. Economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimate that expanding housing supply to drive up availability in high-productivity metros of New York, San Francisco, and San Jose would increase national income by nearly $3,700.

Corporate Power

Corporations have gained significant market power in recent decades, which has allowed them to gatekeep. Through mergers and anticompetitive practices, as well as influencing the regulatory process, dominant firms with key ownership stakes use their outsized power to raise prices and constrain supply. For example, many pharmaceutical companies construct patent thickets to prevent other companies from delivering generic pharmaceutical drugs to market at competitive prices. Dominant corporations are not the only actors doing this. Gatekeeping happens on a smaller scale, too. Occupational licensing can mandate standards and training for professions where that is necessary. But its imposed requirements have expanded in recent decades, creating a barrier to entry for new businesses, like hairdressers and barbers, that benefits incumbents and already established players. This impacts both entrepreneurs and consumers.

“Dominant firms with key ownership stakes use their outsized power to raise prices and constrain supply.”

The impact of growing and historic corporate power on working people’s affordability crisis cannot be overstated. Some important examples include:

- Corporate power drives up health care costs. When hospitals buy up physician groups, those doctors end up raising prices 15% more than independent peers within two years. Market concentration leads to rising drug prices. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) that act as middlemen in the prescription drug industry significantly mark up prices by hundreds and thousands of percent for cancer and HIV treatments, and other critical drugs.

- Meat processors in the food industry gatekeep when they coordinate to raise prices and reduce supply, charging grocery stores higher prices for meat that are also passed on to American families.

- Tech companies that own digital platforms are also powerful gatekeepers. Amazon’s ubiquitous online store gives it visibility into popular products that it then copies to undercut competitors. Or Amazon can acquire successful outlets like Diapers.com, which the e-commerce platform purchased and later shut down, eliminating an affordable online option for diapers and baby care and pushing consumers to instead rely on Amazon in a dwindling field of competitors. Separately, to compensate for losses on underpricing its own products to acquire market share, Amazon has extorted third-party sellers by extracting as much as 45% of sellers’ revenue through predatory fees. These fees force sellers to raise their prices, and not only on Amazon. Because Amazon penalizes sellers that offer lower prices on other platforms, sellers absorb Amazon’s steep fees by raising prices across the board, making things more unaffordable for consumers.

- Corporate power also traps workers in underpaid wages and hostile working conditions because of their power over hiring and labor markets. Firms exercise monopsony power over low-wage workers, who are disproportionately workers of color, by driving wages lower.

- Monopolies deliver fewer options for low-income households. Economist James Schmitz found monopolies frequently follow a pattern of limiting or eliminating entirely product substitutes that low-income households would have otherwise chosen in housing, legal services, dental services, medical care, education, and other basic goods and services essential to their economic well-being.

In the 1970s, the U.S. government embraced an overly-permissive approach to regulating corporate power, leading to its rise as a central gatekeeper in our economy. The Chicago School, which included Richard Posner and Robert Bork, popularized the idea that efficiency should be the goal of antitrust enforcement through the consumer welfare standard. In adopting this short-sighted standard, antitrust enforcers and judges wave mergers through if they determine that the merged firm would not raise prices in the short term—without regard for the long-term effects on market structures and the power that grants corporations over workers, small businesses, and everyday people.

“The goal is to unlock innovation that creates more quality options for working people and safeguard competitive prices that do not gouge people’s budgets.”

We can make a different set of choices that embraces the government’s capacity to manage fair markets and rein in corporate power. Robust antitrust enforcement alongside policies that promote competition are key to eliminating corporate gatekeepers across our economy. The goal is to unlock innovation that creates more quality options for working people and safeguard competitive prices that do not gouge people’s budgets—instead of letting corporate power decide what Americans can afford.

Weak Governance

“A functioning government with strong state capacity can provide public goods, mobilize capital, and deliver basic services.”

Alongside a rise in market power has been a hollowing out of state capacity, which is the government’s ability to implement policies to deliver good outcomes for everyday people. A functioning government with strong state capacity can provide public goods, mobilize capital, and deliver basic services. But state capacity is significantly hamstrung by gatekeepers, both the private actors and special interest groups alike—including Chamber of Commerce and neighborhood Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) groups—that take advantage of government bureaucracies and administrative processes to restrict the supply of essentials working families desperately need. In essence, these groups become the loudest voices in the room. By dominating the democratic processes that are meant to bring the public into shared governance, these groups elevate their demands over the policy goals, hindering the deliverance of shared policy goals. This dynamic, in turn, has amplified the problem, as weak governance serves as a form of gatekeeping itself. The decline in state capacity excuses government inaction and reinforces the failure of government to actually deliver policies that result in tangible improvements and political resonance for everyday people.

One way to make things more affordable is, in the language of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance, is to address “bottlenecks” that prevent government from accomplishing its aims. At the same time, it is equally important to focus on gatekeepers, because many bottlenecks exist because a gatekeeper wants them to be there.

Special interest groups and incumbent firms exert political influence to create bottlenecks and curtail public investment, reducing supply to the detriment of the public and contributing to the affordability crisis facing Americans today. Forms of gatekeeping include:

“It is equally important to focus on gatekeepers, because many bottlenecks exist because a gatekeeper wants them to be there.”

- Gatekeepers can exploit the regulatory process to hamper affordability.

Despite Congress passing a bill in 2017 to require the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue regulations by 2020 that would make more affordable hearing aids available over the counter, the FDA continuously delayed rulemaking until 2022, in part due to the extensive public comment period that allowed dominant hearing aid manufacturers to lobby for weakening the proposed rule. - A court’s recent decision to vacate the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) “Click-to-Cancel” rule shows the same dynamic.

The presiding judge cited procedural issues, using a demand for even more impact studies as pretext to kill the rule that would have benefitted consumers—even as the FTC had already spent three years reviewing thousands of comments and given industry a chance to present at a hearing. - Restrictive zoning and land-use requirements play a central role in gatekeeping the housing market, especially to exclude Black people from primarily white neighborhoods historically.

With housing, the gatekeeper is often a peer, such as local boards and neighbors, who each hold a small veto. As law professor David Schleicher notes, that creates a classic collective action problem: the benefits of saying “no” are local and visible, while the costs, higher rents, longer commutes, fewer jobs, are spread across the whole community. - Empirically, when cities authorize more rental units, especially with by-right approvals and reduced parking mandates, new supply becomes available and nearby rents fall without spikes in displacement.

Studies of increased housing supply find a reduction in rents in the immediate and surrounding areas, with a decreased risk of displacement and an expansion of vacancies; at the national level, loosening supply constraints would meaningfully raise output and wages.

Our goal is to move our economy from defaulting to “no, unless” to “yes, if”, by using state capacity as a tool to break the bottlenecks imposed by gatekeepers. For housing, that involves setting some zoning rules at the state or regional level, creating real housing targets with enforcement, and making it easier to build housing by changing zoning codes and eliminating parking minimums. Embracing the government’s long-standing role in actively shaping markets to meet economic and political goals that are in America’s best interests opens up creative, strategic possibilities in rebuilding our public capacity to deliver policies that best serve communities and families. Through this, we can strengthen our democracy to ensure that markets work for all of us.

“Embracing the government’s long-standing role in actively shaping markets opens up creative, strategic possibilities in rebuilding our public capacity to deliver policies that best serve communities and families.”

Reason 2: Fragmented Markets

For many things, affordability turns on scale. Essential systems like child care, health care, and broadband require providers to take on large fixed costs and uncertain risks in delivering these services. When there are enough buyers and users in a given market, providers can spread those costs across more people, and the price each person pays falls. When there are not enough buyers in thin markets, providers struggle to cover overhead, financing becomes expensive, and firms will provide fewer options. These challenges are especially pertinent in rural markets. As a result, providers leave a gap and ultimately exclude entire rural communities from accessing these essential services. Public options—goods and services provided, authorized, or procured by the government—can address these challenges and play an essential role in filling the gaps to foster competitive markets that deliver the basic goods and services people need.

Lack of Scale Raises Prices

Thin or fragmented markets push costs up. Sellers face uneven overhead costs and pass these expenses on to buyers, increasing economic markups. In health care, many payers mean countless rules, networks, and billing systems. In child care, centers cannot spread staffing and facility costs if enrollment is low, so tuition climbs or slots vanish. In food retail, low-volume in lower-income neighborhoods means grocers often struggle to sustain operations and turn a profit after opening, because pricing matters just as much as proximity to consumers.

“Capital costs bite hardest at a small scale.”

This is also true when it comes to capital costs, which bite hardest at a small scale. Underwriting and servicing costs are mostly fixed, and lenders pass on these costs to borrowers taking out small loans that disproportionately carry higher rates and fees. Thin collateral and volatile cash flow add risk premia that private enterprises with profit motives are not willing to assume. These challenges hit rural communities hardest, where decades of public and private disinvestment have already stifled economic opportunity. Connecting rural residents to essential broadband and electric services requires providers to build out, maintain, and upgrade physical infrastructure over long routes with sparse connections. Private providers often cannot justify the investment since they are unlikely to recoup costs, and thereby underserve the very communities that need these essential services as a result. Rural hospitals face both thin volumes with fewer patients and costly capital, which pushes per-patient costs up and threatens service lines, even when the community’s need is high.

Moreover, administration itself is a significant driver of costs. When the ability to apply for programs or to administer the tax code is dispersed or privatized, costs increase as families cannot access the resources they need. More active administration at scale—like the IRS’s Direct File program that provided low-cost tax filing service to the public—can make a major difference.

Altogether, fragmented markets have serious costs for many Americans, including:

- Deepening the digital divide: 22.3% of residents in rural communities and 27.7% on Tribal lands lack access to fixed broadband, compared to just 1.5% of residents in urban areas. The sparse density in rural geographies means that without municipal and cooperative models or government subsidies for private providers like the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program that cover the up front investments in building out robust fiber or cable broadband infrastructure, these communities only have access to slower, less reliable satellite options for connectivity.

- Only about 61% of unemployed individuals who were eligible actually filed for unemployment insurance benefits. Roughly one-third of children in families eligible for the Child Tax Credit (CTC) did not receive it and each year, about 20% of eligible workers fail to claim the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). These shortfalls reflect infrastructural and administrative barriers in state systems.

- An estimated 18.8 million people, or 6.1% of the U.S. population, live in low-income, low-access areas located more than 1 or 10 miles (for urban and rural, respectively) from a supermarket. Small and independent grocers cannot compete with large chains that can leverage their market power for unfair discounts from suppliers—creating an antitrust issue that could be addressed by enforcing the Robinson-Patman Act. This price discrimination blocks the wholesalers that serve local grocers from realizing pricing that accords to their scale. As a result, price-sensitive families opt to travel farther to buy more affordable groceries at large chains, and these smaller and independent grocers struggle to keep shelves stocked because of unfair pricing and low customer spend.

- Nearly 7,000 hospitals and clinics in rural communities—the majority of rural health care providers today—were opened with federal funding made available from the Hill-Burton Act in 1946 and the Public Health Service Act in the 1970s. The economics of limited scale mean that these facilities often cannot afford to make capital investments that would upgrade their infrastructure, bringing them up to today’s safety and care standards. Instead, they often shutter, increasing prices by 3.6% at nearby hospitals that remain open and leaving rural communities without access to more convenient and affordable care. Health care cuts enacted in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act mean that nearly a thousand rural hospitals are at risk of closing.

“The government has a duty to ensure equal access to public goods that are deemed critical and essential to a flourishing democratic economy.”

Historically, our country has addressed similar problems before. Until the mid-2000s, Comcast had a monopoly on broadband in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Even with a private internet service provider, customers were unable to access faster broadband speeds at affordable prices. To bridge this gap, Chattanooga’s Electric Power Board (EPB), a municipally owned utility, began offering internet services to customers in 2009. They increased mid-tier consumer internet speeds from 5.5 to 100 Mbps in the first year, providing faster service than private providers at similar prices. In 2010, EPB introduced the first one-gigabit-per-second service in the United States. EPB’s fiber infrastructure investment in Chattanooga served as a catalyst for better services for residents and businesses, with better prices and improved quality, and unlocked $2.69 billion in economic value through business and job creation enabled by remote work.

Just like in Chattanooga, we can now deploy scale as necessary to address the problems at hand. Private enterprise may deem certain goods too expensive to build out and provide, no matter the social or economic importance to the communities left behind by these business decisions. But the government is not constrained by the same profit motive or limited scale as private business. The government has a duty to ensure equal access to public goods that are deemed critical and essential to a flourishing democratic economy. When it comes to social insurance, public options can increase access while decreasing costs.

Scale Lowers Costs

In the same way lack of scale makes things more expensive, when it comes to social insurance and key investments, scale can also make things more affordable. As risk pools scale, spending becomes more predictable and shocks cancel out. Size and uniformity reduce overhead, make outlays more predictable, and can get better terms.

Another area where scale lowers costs is income and retirement security. Social Security shows the power of universal coverage: by pooling nearly all workers and retirees together, it delivers benefits with low administrative costs. The long-term perspective the government can take and its ability to guarantee support across decades ensures a level of support for the elderly that an individual’s private account could not deliver. The scale of a broad public program not only lowers costs but ensures predictable, guaranteed income in a way fragmented private markets cannot.

There are many examples of how this works:

- In the current multi‑payer U.S. health system, administrative complexity costs roughly $528 billion annually (1.8% of GDP) due to excessive insurer and provider overhead that could be largely eliminated under public options or single‑payer models. This would both reduce premiums and reduce the federal deficit.

- The opposite is true: Fixed-scale support allows for more reach; Medicaid funding backstops many rural hospitals and health care access in those areas. Recently enacted cuts to Medicaid strip this fixed-scale support, meaning they will lose deeply needed revenue. With anticipated average losses of $630,000 per hospital, or roughly 56% of their net income, nearly a thousand rural hospitals are at risk of closing.

- Social Security demonstrates how scale can drive affordability. With administrative costs accounting for under 1% of benefits paid, it operates far more efficiently than private retirement accounts, where fees eat away at savings. The scale of Social Security delivers predictable benefits and lowers costs for households, especially low-income families who would otherwise face high fees in fragmented financial markets.

The scale of public social insurance is an important part of being able to solve these problems. When it comes to managing risks, the larger the risk pool and the longer the horizon, the better the outcomes will be. Sometimes firms pursue scale as a strategy to achieve market dominance, too, which not only requires solutions to break up gatekeeping, but underscores the real risks of relying on private enterprise to deliver public goods. The public itself, providing insurance against these risks, can take the lead.

Manipulated SignalsReason 3: Manipulated Signals

In a market economy, prices are a means to communicate information. They can help convey how scarce a good is, whether it is in high demand or low supply. But sometimes this information mechanism can break down. This is true even when there appears to be strong competition in a market without a single dominant seller because pricing opacity takes advantage of information asymmetries and undermines consumers’ ability to compare true prices, thereby reducing or even eliminating price competition.

These pricing strategies drive unaffordability in two ways. First, sellers manipulate pricing signals by building in hidden costs to deceive consumers, making it easier to extract rents by obscuring the real or total price they charge working people. Second, sellers price goods or services too high or too low if they account for, or fail to account for, positive and negative externalities. Both trends obscure the true costs of goods and services, which makes a real difference in people’s pocketbooks.

Bad Information

Instead of innovating to bring new, better products or otherwise adding value to justify higher prices, firms compete on obfuscation by manipulating the consumer experience. By leveraging pricing strategies that deceive consumers by charging more than what things cost, firms not only prey on consumers, but also gain an unfair advantage over competitors that offer transparent pricing.

Firms utilize partitioned pricing practices that show only a base price, tacking on separate mandatory fees that are revealed only when the consumer has already spent time evaluating options and nearly completed checking out their purchase. By making the total price less salient, sellers corner buyers into bait-and-switch situations. When people cannot see or make sense of the real price, they cannot choose a better option by comparing offers and walking away from bad ones.

Sometimes firms price goods and services based on specific, individualized data, instead of aggregate supply and demand. This practice is known as personalized pricing. In the digital age, firms that collect customers’ data can leverage it as a competitive advantage and charge different prices for different customers, even if the product or service is identical, padding their profits and making it harder for price-sensitive consumers to get what they need. Dynamic pricing exacerbates this problem by allowing sellers to change prices based on changing market conditions in real-time, enabling firms to maximize profits by ensuring that they are always charging the highest price that consumers are willing to pay.

The harms are meaningful. Consumers are forced to spend more time trying to make sense of their options, and ultimately spend more money than expected. Alternatively, they may give up, exasperated by the lack of transparency, and go with the option that appears most affordable based on the initial base price advertised, even if they would have rejected that option if the total price had been clear up front in their search. Competing firms that advertise transparent prices lose out to firms that utilize partitioned pricing. The burden falls most on those with less time, less cash, or less financial literacy with pressing, timely needs: the parent who needs baby formula or diapers, the patient who needs their prescription filled, and the worker who has bills to pay.

“Firms compete on obfuscation by manipulating the consumer experience.”

Various types of opaque pricing include:

- Surprise billing and opaque networks in health care services mean patients often learn the cost of an emergency room (ER) visit or a procedure only after they are already committed. On average, 18% of in-network emergency visits result in a surprise bill ranging from less than $500 to over $2,000.

- When firms charge junk fees—fees that are hidden, revealed late, or wrapped in complexity—the usual feedback loop that might compete them away fails. Headline prices stay low, profits move into add-ons, and pressure to compete on the true total price weakens. Hotels promote attractive nightly rates, then add resort or destination fees at checkout. Airlines charge for bags, seat selection, and changes. Ticket platforms layer on service charges. Banks rely on overdraft and nonsufficient funds (NSF) fees. In total, these hidden fees cost the average American family over $3,200 each year.

- Using personal data like location, demographics, credit history, and browsing history as real-time signals, firms can leverage surveillance pricing to set personalized prices for different customers buying the same product. Until they walked back this decision because of regulatory pressure, Delta was exploring using AI to set personalized prices for airfare. A class-action suit alleged that DoorDash charged iPhone users higher prices for food delivery than Android users.

- Companies can also automate personalized pricing through algorithms that take advantage of information asymmetries and changing market conditions in real-time. For example, in labor markets, rideshare drivers and nurses are paid different wages based on changing algorithms. The lack of transparency into how these surveillance pricing and pricing algorithms operate gives rise to the possibility of algorithmic collusion and price-fixing, even without competitive data exchanging hands directly. Corporate landlords, for example, were able to charge 4% higher prices, an average of $70 a month, in housing rental markets across the country using RealPage’s algorithm. Without robust guardrails in place, these trends risk becoming commonplace across the economy, driving up costs for basic essentials like groceries, health care, and more.

Companies should not be allowed to get away with these predatory pricing strategies. Policymakers and the public should demand that sellers show the full price up front. New regulations like banning junk fees would help standardize disclosures so that consumers can do easy comparisons. Transparency restores price discovery, shifts competition to the number that matters, and rewards genuine value rather than the ability to hide the ball.

“The burden falls most on those with less time, less cash, or less financial literacy with pressing, timely needs: the parent who needs baby formula or diapers, the patient who needs their prescription filled, and the worker who has bills to pay.”

Externalities

Externalities are spillover costs or benefits that fall on people outside a specific transaction. Those spillovers result in indirect costs that do not fall on the supplier or user, but instead on third parties or the broader public. When firms set prices that fail to capture those spillovers, they steer consumers into making non-optimal choices. When firms set prices that do capture those spillovers, they drive up costs and push goods and services outside the realm of affordability for families.

These are risks that families cannot individually manage or avoid. A family might try to budget carefully, but if the air is dirtier, the commute is longer, or the grid is less reliable because of decisions elsewhere, their costs rise all the same. Externalities shift expenses off the balance sheets of firms and on to the balance sheets of households, making affordability less about individual choice and more about how markets and policies handle these hidden spillovers.

Externalities directly affect consumers’ household bills in a number of ways across sectors:

- Pollution is the clean example. Energy producers charge posted prices that omit health and climate damage, so harmful goods like fossil fuels look cheap and attractive to consumers, and the pricing incentivizes fossil fuel consumption. Traffic congestion works the same way. Each trip slows others, yet the driver does not pay for the delay and the resulting pollution. A charge at crowded times corrects the signal and frees space.

- Negative externalities like rising climate risk increase insurance premiums, taxes for disaster response, and utility costs for grid hardening that are all directly passed on to consumers.

- As AI transforms our economy, data centers’ electricity use has tripled in the last decade, and is projected to double or triple by 2028. These substantial loads require utility grid expansions like new power plants and transmission lines that are subsidized by consumers, even if data centers use a disproportional share of the energy. Researchers are pointing to data center load growth as the primary reason for high electricity prices, resulting in $9.3 billion in increased revenue just last year alone. The Natural Resources Defense Council estimates that the average family serviced by grid operator PJM will pay approximately $70 more per month on their electricity bills because of forecasted data center growth.

- Positive spillovers can make things more affordable yet are underprovided. Education boosts not just the student but coworkers and future firms. Basic research seeds ideas others turn into cheaper goods and better services.

“Externalities shift expenses off the balance sheets of firms and on to the balance sheets of households, making affordability less about individual choice and more about how markets and policies handle these hidden spillovers.”

Policymakers can and should optimize prices to strategically account for these externalities. Policies can pair social costs and benefits with prices or clear standards to steer people toward different choices, or pair any charge with better alternatives so behavior can shift without losing access. We can also use the revenue to expand options that lower costs over time. Direct provisioning of public goods and services can bring down costs for services where externalities impose significant costs, making them more accessible and affordable for families. Transparency and aligned incentives between provider and consumer move the system toward value rather than hidden spillovers.

Broken IncomesDriver 2: Broken Incomes

Coupled with broken markets, broken incomes are a key reason why basic necessities feel perpetually out of reach for too many Americans: even when markets work well, people do not have the income they need. This stems from both a set of policy decisions over the past several decades that have contributed to widening inequality, and built into how a market economy functions. Despite external volatility and fluctuation, there is a simple misalignment between today’s costs and individual’s incomes, trapping people in economic precarity.

Life Cycle MismatchesReason 1: Life Cycle Mismatches

Even if markets are working well, key essentials of life can still be unaffordable, especially during two major earning crunches during a person’s life: early adulthood, when earnings trend low due to people starting their careers and working entry-level jobs, and retirement, when income is fixed and capped by what they were able to save up earlier in their lives. As a matter of theory, economists often just assume people can smooth their spending over their lives, and downplay these problems as a result. But the real world doesn’t work that way, and whether it’s uncertainty, risks, concerns about the future, or the sheer difficulty of smoothing income over long periods, the data point to the fact that people do not have the money when they most need it. When cash is tight as transitions and big needs arrive, the effective price of essentials becomes unaffordable, no matter how much supply there is.

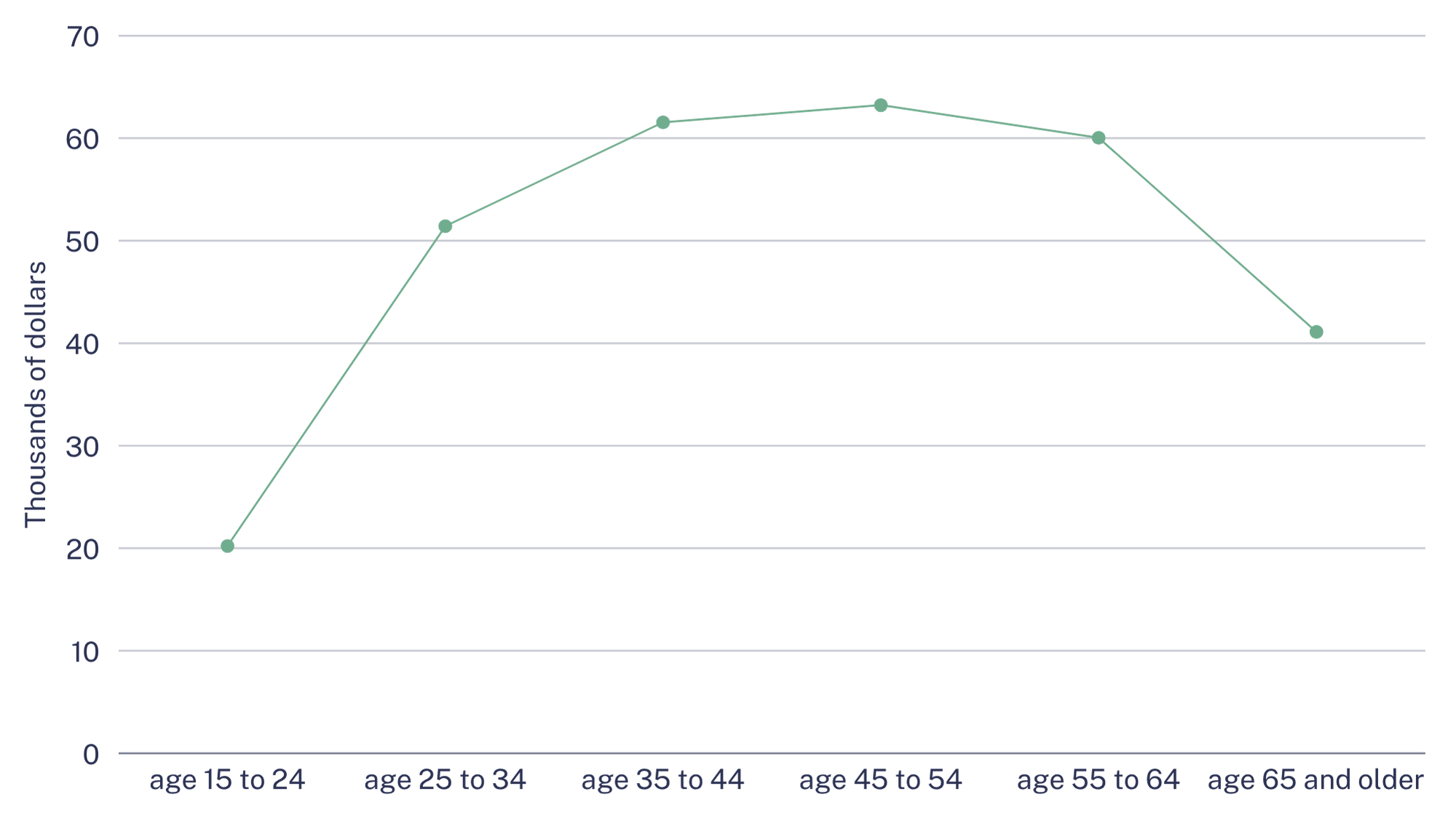

Annual Earnings by Age

U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2024-2025

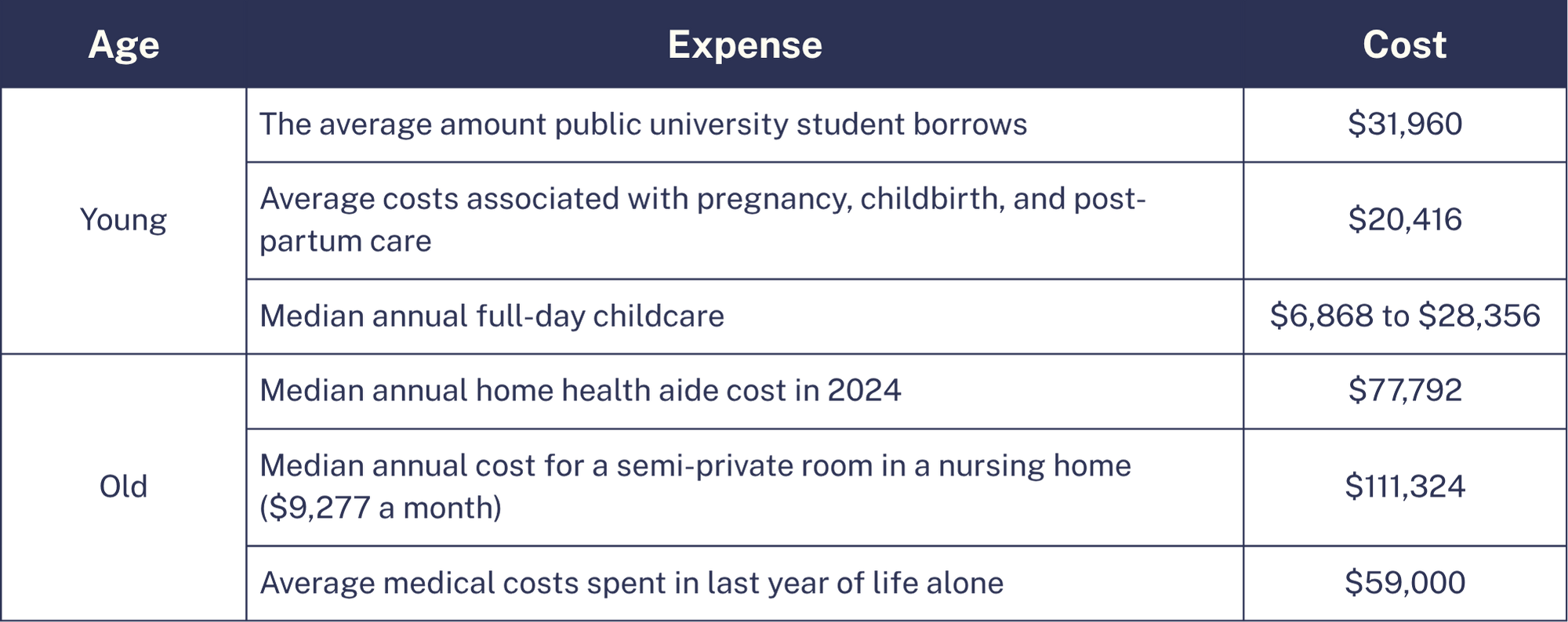

Peak Earnings Are Out of Step With Life Events

Sources: Education Data Initiative, Kaiser Family Foundation, Economic Policy Institute, Genworth Life Insurance Company, CareScout, and the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey

The mismatch between life and earning cycles is no accident of timing—it is baked into the nature of how incomes are earned and costs incurred in a market economy. As the policy analyst Matt Bruenig writes:

Put simply, the distribution of income in a capitalist economy is at odds with the rhythm of human life and especially the rhythm of family life. Childbearing comes too early to amass savings. Income arrives too late to finance contemporaneous child-related expenditures. […] This mismatch between peak earning years and peak childbearing years drives up inequality and poverty in society.

“When cash is tight as transitions and big needs arrive, the effective price of essentials becomes unaffordable.”

It is also amplified by decades of disinvestment from public goods and social insurance that have left families stranded and financially precarious without a strong social safety net. Homeownership as a vehicle for wealth building has become much more expensive for younger generations. Raising a child has gotten more expensive; the Brookings Institution estimates that a middle-income family spends $310,605 to raise one child through 17 years old. At the other end of life, retirees discover the foundations they were told would secure old age are under siege. Understanding early-life and late-life burdens as parts of the same system makes clear that the problem is not individual failings, but a political economy that has shifted risks on to families while stripping away the public tools that once balanced them.

Early Career Earnings and Early Bills

Earnings usually climb with work experience and often peak in the forties or fifties. According to the latest Census data, workers ages 15 to 24 years old earn a median of $20,220 and workers ages 25 to 34 earn a median of $51,420. Median earnings are highest for workers ages 45 to 54 years old at $63,230.

“These up front investments and early career costs set up a vicious cycle as working families face impossible choices.”

Yet many bills hit families earlier than these peak wages:

- Raising children is expensive. In 2023, the average first birth is at age 27.5. Infant and toddler care is labor intensive; annual child care costs commonly run ten to twenty thousand dollars, a double-digit share of a typical young household’s income. These costs are further compounded for adults in the “sandwich generation” who find themselves shouldering the burdens of raising young children and caretaking for aging parents simultaneously.

- There are additional costs with raising a family that expand well before earnings peak. Families who want to move to get additional space must scrap together the first month’s rent, a security deposit, and moving costs all at once. To offset rising housing costs, the number of families living in multi-generational households has quadrupled since the 1970s. A reliable car adds to the budget, as well as medical costs with pregnancy and raising a young child. Costs associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and post-partum care average $20,416, including $2,743 in out-of-pocket expenses for pregnant people enrolled in employer plans. Unpaid leave turns time off into a hidden bill.

- Education and training require large payments years before the wage return arrives. Higher education on average requires an up front investment of $38,270 per year. To help pay for tuition, the average public university student borrows $31,960. Trade schools and apprenticeships offer more affordable career training alternatives, but still require tuition fees ranging from nearly $4,000 to over $15,000.

These up front investments and early career costs set up a vicious cycle as working families face impossible choices. Young graduates start careers saddled with student loan debt. Larger families suffer higher poverty definitionally because there are more people to care for on a given set of incomes. Career paths get disrupted. To bridge the gap in child care, a parent (disproportionately mothers) often cuts hours or steps out of work. That means lower earnings today and slower wage growth tomorrow.

We have seen how powerful the tool of social insurance can be in small expansions of pre-K. Numerous studies find that access to child care increases women’s employment rates. One recent study that tracked parents found when pre-K was made available in New Haven, Connecticut, parents, especially women, were able to maintain continuity of their careers easier. The resulting economic gains were six dollars for every one dollar spent; a benefit-to-cost ratio of 6:1 is one of the highest known values in policymaking. By providing reliable day care, the program allows parents to sustain careers and family routines with less stress and disruption, giving families greater stability and dignity in their daily lives. The authors also acknowledge how difficult it is for parents to try and borrow against these potential higher incomes to get child care earlier; the life cycle mismatch is evident.

Social insurance should meet families where they are and when they need it, not years later. Providing families with a buffer against economic risks that come with major life events can unlock economic benefits far beyond the initial event. Solutions that directly respond to families’ immediate needs, like expanding child care services, for example, can both ease household budgets and maximize caretakers’ earning potential. Tax credits like the CTC and the EITC can also provide families with much-needed cash, especially if paired with a boost during a baby’s first years. Social insurance builds affordability throughout the life cycle. It’s the clearest and best way to make family life affordable.

Retirement and Late Life Costs

My husband and I retired and went on the marketplace to get insurance. We were paying our premiums. Come income tax time, we had to pay all that money back because they said we weren't eligible, that we made too much. You know how much we had to pay back? $25,000. So, we went back to work.

— Residents of Springfield, IL

The economics of aging mirror the early life crunch. Earnings are weak or absent as health and care needs grow when people enter their golden years. Median earnings for individuals 65 years and older drop to $41,110. This has historically caused a high rate of poverty for elderly people, especially as the economy moved from agriculture to industry, where it was harder for older people to productively add to family enterprises. Before Congress created the Social Security program in 1935, people who could no longer earn enough money to survive often had to rely on the poorhouse. After Congress created Medicare and expanded Social Security in 1965, poverty rates among the elderly, which had remained quite high, plummeted. In 1965, seniors were the group most likely to be living in poverty; nearly 30% of seniors were poor. Today, if not for Social Security, 37% of seniors would be living in poverty—with Social Security, that number drops to just 10%.

With that in mind, there are still acute costs that weigh heavily on senior households, many of whom are on fixed incomes, including:

- Long-term care costs like home health aides are $77,792 annually in 2024. The median cost for a semi-private room in a nursing home is $9,277 a month, and that’s when spots are available. Specialty care facilities for mobility support or memory loss are even more expensive. Families do their best to fill in the gaps, but they can only do so much. Family caregiving also comes with high opportunity costs, especially as younger generations also have to build their own savings to fund their own retirement and procure immediate family needs. Women, especially Black women, disproportionately shoulder the burdens of eldercare by giving up paid work. These costs of unpaid care provided by family members total $600 billion.

- Health care costs more than double from the ages of 70 to 90 years old. In the last year of life alone, elderly people spend $59,000 on average on medical costs. While the government pays for over 65% of health care spending by the elderly through Medicare and Medicaid, a significant portion self-finance or use private insurance to pay for these costs.

- Nearly 11.7 million senior households spend over half their income on housing, a number that has doubled over the past two decades. Seniors over 75 years old are more likely to be cost-burdened by housing than younger seniors. Renters are more likely than owners to be cost-burdened at all ages.

“Social insurance can help balance incomes throughout people’s lives, channeling earnings to new families to support children and to the elderly to support a dignified retirement.”

Forms of social insurance like Social Security and Medicare are designed to address these life cycle challenges. For 40% of beneficiaries, Social Security provides half of all income. These programs are not enough to cover all the gaps, but they set a strong foundation to build on. Creative solutions like expanding Medicare to include the costs of home modifications seniors need as health and mobility requirements change with aging can support hardworking families. Social insurance can help balance incomes throughout people’s lives, channeling earnings to new families to support children and to the elderly to support a dignified retirement. With these tools, we can smooth out the disconnect inherent in a market economy.

InequalityReason 2: Inequality

Rising inequality also contributes to and exacerbates unaffordability. Paychecks are simply too small at the bottom of the income bracket, and being poor is expensive. Increased inequality at the top of the income distribution means more of what our economy produces goes to the very rich, who can bid up the price of select goods and steer markets to cater to those with resources. It is often a self-reinforcing cycle where poor people are penalized for not having enough time or money as corporations exploit what they can from working people.

Insufficient Incomes

Tens of millions of families are caught in a bind and forced to make difficult choices daily as they try to stretch every hard-earned dollar, weighing the urgency of each pressing need. As many as 43% of U.S. families do not earn enough to pay for basic necessities like housing, food, health care, child care, and transportation. These numbers are even higher for Black and Hispanic families at 59% and 66%, respectively, compared with 37% of white families. Families with insufficient incomes, meaning they do not make enough to afford what they need, are a major driver of the modern widespread affordability crisis. As families confront these impossible choices between needed essentials, they make harmful decisions that come with trade-offs.

Is the new American dream working three jobs?

— Resident of Omaha, NE

Inequality also means those with very high incomes can outbid everyone else for scarce items when supply is limited. The rise and persistence of inequality have played an important role perpetuating disparities within incomes and between labor and capital incomes:

- The share of national incomes going to the top 1% has risen steadily since 1980, more than doubling from 10% of income to over 20%, with a sizable increase during the pandemic.

- The labor share, the share of incomes going to workers, has fallen dramatically since the year 2000, to the lowest levels since records began in the 1950s. It fell again during the COVID years as prices skyrocketed and corporate margins increased, but never reverted.

- Worker wages have not matched productivity growth since 1979; productivity has grown 2.7 times as much as pay. In 2023, the U.S. Census Bureau found that the median annual earnings for all workers was $60,192, with the median man making $64,705 compared to the median woman making $52,458.

There are many reasons for this gap, ranging from declines in the real federal minimum wage, declining worker bargaining power as unionization fell, tax-code changes that privilege corporations and the wealthy, and deregulatory approaches that failed to check private power.

43%

of families lack income for basic necessities

0.6%

annual real wage growth since 1979

While real median wages have not been entirely flat over the past three decades, the Economic Policy Institute describes them as having been “suppressed.” According to their analysis, since 1979, median wages have risen only about 29% in real terms, less than 0.6% per year over that 45-year span, even as productivity has climbed roughly 83%. Nearly all of those wage gains came during periods of sustained low unemployment. Excluding the years 1996–2002 and 2014–2024, real wage growth has been essentially zero. This widening gap between productivity and pay is why bringing inequality into the picture is so important.

There are a set of solutions that could be deployed to lower inequality and ensure economic growth benefits everyone more broadly. Progressive taxation is an important check on runaway incomes at the top of the distribution, both in terms of redistribution and structuring the economy to keep executives from gaining outsized pay. But taxation has become more regressive in past decades. Moreover, recent widespread tariffs enacted in 2025 have acted like a poorly-designed consumption tax on families; their main effect was to help cover the cost of tax cuts for wealthy households. These tariffs are widespread and not strategically targeted to boost leading industries; they also have a stagflationary effect that makes more things unaffordable. According to leading estimates, the tariffs will lead to an average household loss of $2,400.

The weakening of labor unions and the erosion of worker power contribute to broader trends of lower wages and higher corporate profit shares. We can build a more affordable economy for all of us by closing the gap that working families face, restoring opportunity and agency for all.

The High Cost of Being Poor

Inflation drives up costs for all families, but poorer families feel these price hikes much more sharply. The Brookings Institution found that the cost of being poor is rising, especially for Black and brown families The high cost of being poor shows up most clearly in the everyday trade-offs families have to make. Poor families pay more for basics because they cannot buy in bulk or afford the memberships that cut prices for wealthier households. Without good credit, renters face bigger deposits, steep late fees, or have to rely on high-interest loans when an unexpected bill hits. When families face limited access to supermarkets, they are forced to shop and pay more at corner stores or fast-food chains, while unstable health insurance means preventive care is skipped and expensive ER visits become the default doctor for many. An individual that earns a small raise might mean more household income to allocate to these essentials, but it also comes with a trade-off and the potential of being pushed over eligibility thresholds for programs like Medicaid. On top of that, overdraft charges, check-cashing fees, and high utility bills from older, inefficient housing stack the deck further against poor people. Low-income people are often unable to access reliable mainstream banking and are at the mercy of predatory credit services and payday lenders.

Groceries are just going up like crazy. You have to choose, am I going to pay rent or I'm going to eat?

— Resident of Chicago, IL

Poverty also exacts a “time tax.” Low-income families are forced to spend far more hours navigating systems and barriers than wealthier households. They may lose an entire day waiting in line for public benefits or making multiple trips to resolve a simple paperwork issue. Time spent on reporting work requirements attached to programs like SNAP and unemployment takes away time from job searching. Inflexible work schedules can mean people are forced to commute on slow buses or trains that can eat up hours. Arranging child care or medical appointments often requires accommodating limited, unreliable options at set times that do not align with people’s work schedules. The result is a constant drain of time and energy, where every task takes longer and every setback has a bigger ripple effect.

A few trends to contextualize the high costs of being poor:

- Low-wage workers make too little income to meet minimum standards of living. According to measures like the MIT Living Wage Calculator, the costs for food, child care, health care, housing, transportation, internet/phone services, and taxes—which enable families to achieve a reasonably minimum standard of living—all substantially exceed the federal poverty line. These costs vary by geographies. In a higher-cost urban setting like Queens County, New York, these family budget measures ranged from $110,959 to $150,319. In a lower-cost rural setting like Grant County, Washington, these measures ranged from $75,397 to $104,960.

- Nearly 60% of people do not have three months of emergency savings or cannot afford a $2,000 emergency expense according to Federal Reserve survey data. Unequal access to credit further exacerbates this divide: many unbanked families turn to payday lenders and check-cashing services that charge predatory, high cost interest rates and fees to cover emergency expenses and pay for daily necessities.

Addressing the high cost of being poor requires removing the structural barriers that make daily life more expensive for families with the least. That begins with policies that provide real financial security, such as a guaranteed income or an expanded CTC, alongside efforts to bring down the cost of essentials like housing, health care, and transportation. The IRS’s now-defunct Direct File program has shown that the government can simplify systems and save households both money and time, the type of model that should be expanded and replicated. Restoring postal banking would do the same for financial services, offering a safe, low-cost alternative to payday lenders and check-cashing outlets for people who otherwise cannot access reliable banking. This step, coupled with fair scheduling laws and stronger worker protections to reduce the “time tax,” would relieve immediate burdens and build the foundation for long-term economic security.

Macro TrendsReason 3: Macroeconomic Trends

In addition to insufficient incomes and the high costs associated with being poor, there are broader macroeconomic trends that break incomes across the entire economy. There are two in particular that stand out: first is the upheaval of the business cycle in recent decades, where both deep economic recessions and sharp, inflationary price increases drive unaffordability. The second is long-term trends in productivity, where we collectively can grow richer but key care needs may continue to grow relatively more expensive over time. Though these are major challenges, they are addressable challenges with a set of proactive policy solutions and bolstered public capacity.

“Nearly 60% of people do not have three months of emergency savings or cannot afford a $2,000 emergency expense.”

Recessions and Inflation

Economic shocks like recessions and inflation do not just show up in statistics; they can upend and reshape people’s lives. When recessions hit, jobs vanish, incomes fall, and public services are strained at the peak moment families need them most. When inflation spikes, the value of a paycheck shrinks and everyday essentials become harder to afford, with the sharpest pain felt by households already living on the financial edge. The past two decades have shown both extremes: the deep, grinding unemployment of the 2008 Great Recession was followed by the sudden collapse of work during the pandemic lockdowns, followed by the inflation surge of 2021–2022. Each episode exposed how fragile household finances are and how damaging economic instability can be.

During the Great Recession, the unemployment rate reached 10% and the number of jobs quickly fell by millions. Worse, it took nearly a decade for the labor market to recover. In the early months of the pandemic, the unemployment rate spiked into the teens and 20 million jobs vanished. Following that spike, major shocks hit the economy, causing the price of all goods to jump 18% from 2021-2023. Real incomes went negative before recovering.

No one individual or family can insure themselves against these risks. This fragility helps explain why affordability is never just about averages or aggregates, but has the potential to deeply impact families at all levels of the income ladder. A single recession can wipe out years of household progress, while a short burst of inflation can make even stable wages feel inadequate. These shocks show how affordability depends not only on what families earn or what goods cost, but on whether the economic floor beneath them is steady or constantly shifting.

It's affecting people in different classes. Even now, you got a lot of folks that are losing their job in the middle class and becoming homeless for the first time.

— Resident of San Jose, CA

The damages of both recessions and high inflationary periods are widespread and last far beyond the immediate downturn:

- Workers displaced in deep downturns can lose the equivalent of two to three years of pre-shock pay over their careers. Even after finding new jobs, wages remain lower for decades, cutting household capacity to afford housing, health care, and education. Graduating into a recession carries a similar penalty, with earnings depressed for 10 to 15 years.

- Major recessions leave economies producing fewer goods and services than they would have without the downturn, and they rarely make up that lost ground. This long-term drag translates to slower job growth, smaller public budgets, and persistently tighter household finances, compounding affordability pressures for years.

- Higher unemployment carries steep health and social costs. A 1% rise in joblessness is linked to a 6% increase in male mortality, along with lasting increases in chronic illness, depression, and family instability. These outcomes raise both public health care costs and private spending, further straining affordability during and after recessions.

- These trends curtail private investment in a way that has long-lasting consequences. For example, housing production collapsed during the Great Recession, with millions of new homes still missing today because of the prolonged nature of that recovery, adding to today’s access and affordability housing crises.

- High inflation erodes real wages, especially for households with little savings. It drives up everyday costs—rent, groceries, utilities—faster than paychecks, pushing families into debt or forcing cutbacks on essentials. Inflation also hits small businesses, renters, and people who do not switch jobs harder, as they lack the bargaining power or financial buffers that large firms and wealthier households use to adjust.

We can support policies to address falling incomes and better absorb inflationary shocks. This will become increasingly important as we navigate new and unprecedented economic shocks, such as a warming world which could lead to risks of growth becoming more volatile. One policy tool, automatic stabilizers, can effectively play this role and help with affordability challenges that any individual faces, and stabilize the economy as a whole. An automatic stabilizer such as unemployment benefits, public health care, or fiscal aid to states and localities can adjust with fluctuations in the market to create stability in the economy.

“When inflation spikes, the value of a paycheck shrinks and everyday essentials become harder to afford, with the sharpest pain felt by households already living on the financial edge.”

Tackling inflation shouldn’t mean simply cooling demand through unemployment. Though Federal Reserve independence is important to keep inflation low and steady, we can supplement this with policies that reduce families’ exposure to price spikes. Strategic supply reserves could be expanded beyond oil to essential inputs for production in case of emergencies. A national housing fund could break the boom-and-bust cycle of housing construction and the business cycle, allowing for more stable and abundant housing. But it also calls on a broader agenda that includes investing in renewable energy to cut exposure to fossil fuel shocks, enforcing stronger antitrust laws to limit price-gouging in concentrated industries, expanding public options to take essential items out of volatile markets, and strengthening renter protections alongside building more affordable housing. These policies confront the root causes of rising costs when they result from supply shocks and ensure families can weather price shocks without sacrificing economic security.

Productivity Trends

Some essentials do not lend themselves to rapid productivity growth. As the rest of the economy gets more productive and wages rise, time-intensive sectors like care and education must raise pay too, even if their output per hour doesn’t jump. That’s an observation economists call Baumol’s cost effect. It’s a potential force behind rising relative prices in care, education, and parts of health care.

Assuming this is important, we must realize that this is a challenge that comes with prosperity. That our economy is more productive and richer is an opportunity to insure households against the costs that remain, because these are the services that make a decent life possible and they should be bought collectively.

“A richer nation should not leave essentials like care, education, and health drifting out of reach.”

To give an overview of how the cost of services, like child care, have increased faster than other items, a couple key facts to highlight:

- The cost of services has increased much faster than the cost of goods. Since 2000, the price of goods, which includes both everyday items like clothing and long-term purchases like appliances and automobiles, has increased 24%. In comparison, the price for services, which includes labor-intensive essentials like child care, health care, and education, has increased significantly more, by 105%.

- At the same time, the country has become far wealthier: real GDP is up 70% since 2000. The gains have not been evenly shared, with inequality in both wages and wealth masking that prosperity. But that’s exactly why we can afford to do better. A richer nation should not leave essentials like care, education, and health drifting out of reach. We must channel our collective wealth into making these services universally affordable, by financing them fairly and delivering them as public goods rather than expensive private burdens.

This wedge between service costs and domestic wealth shows why affordability is a political choice. Policymakers should not wish away the cost effect, but channel it for the common good.

That means rethinking both financing mechanisms and delivery systems. Collective financing spreads time-intensive costs across society, rather than leaving them to individual households. Public programs like Medicare, Social Security, or universal pre-K take markets where productivity growth might be limited and make them affordable by subsidizing their costs. On the delivery side, rules and investments can raise productivity where possible, by reducing administrative bloat in health care, improving technology in classrooms without cutting quality, and streamlining licensing or regulations that artificially restrict supply.

The bigger picture is this: rising service costs are not a sign of failure, but of success. A rich country spends more of its income on human services because that is the investment required to ensure stability and a good life. The call for policymakers is to democratize these costs, not to suppress them, turning the Baumol effect from a threat to affordability into a rationale for universal guarantees and human flourishing.

ConclusionConclusion

The health and future of our democracy depends on our ability to create an economy that works for everyone. Without a functioning economy, Americans become disillusioned by the institutions meant to deliver stability and uphold our democratic values. When the economic system becomes as broken and unequal as it is today, we must restore the social contract by addressing the distress felt by millions of families that are vulnerable to economic and political volatility.

I don't think it's that complicated to think that we should have a government that takes care of us.

— Resident of Venice, IL

America’s affordability crisis is not inevitable. It’s the product of deliberate choices made by powerful economic actors and compounded by decades of policy neglect. These powerful actors assert influence over politics, create strong incentives for policymakers to stay stuck in inertia, and blame individuals themselves for these broader societal problems.

Just as choices created this crisis, new choices can address it. Building an affordable economy requires intentional market-crafting: breaking gatekeeping power and building institutions that ensure universal access to essential goods and services. It also demands a social insurance system steady enough to support people across life’s predictable arcs and strong enough to address long-term challenges. Together, these strategies can inform a blueprint for affordability.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Jared Bernstein, Ben Chin, Emily Divito, Chris Hughes, Jamie Keene, Stacy Mitchell, Aisha Nyandoro, Liz Pancotti, Sabeel Rahman, Bharat Ramamurti, Brian Shearer, Anisha Steephen, Dorian Warren, and Felicia Wong for providing feedback on early report drafts.

Our team at Economic Security Project supported this report: Anna Aurilio, Chrissy Blitz, Adriane Brown, Mary Durden, Natalie Foster, Shafeka Hashash, Taylor Jo Isenberg, Erion Malasi, Mona Masri, Teri Olle, Harish I. Patel, Christelle Prophete, Adam Ruben, Sarah Saheb, and Kelli Smith reviewed drafts; and Michael Conti managed the production, design, and layout.