Report

Guaranteed Income: A Primer for Funders

05. 16. 2022

Learn about ways in which guaranteed income and related cash-based policies not only strengthen low and moderate income communities.

Executive Summary

Guaranteed income, sometimes called guaranteed basic income or basic income, is a cash payment provided on a regular basis to members of a community with no strings attached and no work requirements. It is intended to create an income floor below which no one can fall. While Universal Basic Income (UBI) is a regular cash payment to all members of a community, guaranteed income could be targeted or universal, but focuses on specific individuals within a community, ensuring that those with the greatest need are prioritized for assistance. Targeting can be less costly and more efficient at reaching particular groups. However, because targeted policies tend to engender more narrow constituencies, their political support tends to be more narrow and, thus, harder to achieve and sustain. On the other hand, universal programs, such as Social Security (including SSI) or universal education, are broad in scope and coverage, thereby increasing the number of people who have access to them compared to targeted programs. Because of their universal eligibility, universal programs have had the greatest potential to engender and sustain broad political support. However, they often fail to address existing disparities between different groups of people. Targeted universalism responds to the shortcomings of targeted policies that exclude many and universal policies that treat everyone equally (powell et al., 2019).

While the idea of guaranteed income has a long and varied history dating back to Roman Times, its modern, progressive origins in the U.S. are rooted in the racial and gender justice movements of the 1960s (Bhattacharya, 2019). More recently, the Magnolia Mother’s Trust program launched its first cohort in late 2018, providing Black women in subsidized housing in Jackson, Mississippi a guaranteed income while the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED) was launched in February 2019 by former Stockton, California Mayor Michael Tubbs as the nation’s first mayor-led guaranteed income initiative.

COVID-19 spotlighted the need to rethink policies providing income supports to help all people meet their basic needs, particularly low and moderate income households most vulnerable to economic shocks. However, beyond a means of achieving an array of stabilizing and beneficial outcomes, guaranteed income also serves as an important general protection against a wide-range of economic and noneconomic shocks. It is precisely the flexibility of unrestricted money that provides individuals with agency and a way of addressing the needs they experience as most pressing in their lives. In this way, unrestricted cash assistance is swifter, more flexible and responsive than in-kind assistance, such as food, clothing or even housing.

While guaranteed income is often considered a regular cash payment made by the government, philanthropic funders are playing a strategic role in advancing this evidence-based solution in four major areas: direct service efforts that test and refine what a scaled-up program could look like; system- and capacity- building efforts that build the broader field; policy and advocacy efforts that ensure the longer-term political viability of cash-based policies; and research and innovation that strengthen the case for cash by building needed evidence. All are necessary, strategic investments to achieve impact and scale.

Funders are also playing a critical role supporting reform and expansion of existing cash-based government policies, including the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Child Tax Credit and similar state-level refundable tax credits. They are also supporting reforms of other public policies by applying guaranteed income principles that streamline access and remove onerous or inequitable requirements (Anderson & Kimberlin, 2021).

Programs that put cash into people’s pockets*

EITC

The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a refundable tax credit for low-income families and the largest cash transfer program for low-wage workers, delivering $70 billion annually to 16 percent of all families. The federal EITC is only available to those with earned income and provides very little to workers without dependent children at home. In 2022, 28 states and the District of Columbia will offer Earned Income Tax Credits in addition to the federal EITC. Recently, Illinois expanded its state EITC to include childless workers and immigrants who file taxes with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN).

CTC

The Child Tax Credit (CTC) helps working families offset the cost of raising children. The American Rescue Plan Act expanded the number of families eligible and increased the amount the federal CTC provided most families with kids for tax year 2021. Changes included making the credit fully refundable so that families received the full amount without an earned wages requirement, expanding eligibility to include 17-year-olds, increasing the benefit from $2,000 to $3,000 per child (or $3,600 per child under 6), and paying half of the monthly credit in advance. The expanded CTC payments kept an estimated 3.6 million children out of poverty, a 29% reduction that was reversed when the credit expired.

Guaranteed Income Demonstrations

Building on the success of the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration and the Magnolia Mother’s Trust, as well as the impact of the COVID stimulus payments and CTC expansion, dozens of leaders across the country have implemented guaranteed income demonstrations in their own communities. In early 2022, there were more than 90 demonstrations planned or in progress in the United States. The majority of these have relied primarily on philanthropic funding, although there is an increase in public funding, primarily through use of American Rescue Plan Act funds.

*Please note that this is not an exhaustive list of safety net benefits, but instead focuses on unrestricted cash programs. For more information, visit Section V. of this report, Related Cash Policies.

IntroductionIntroduction

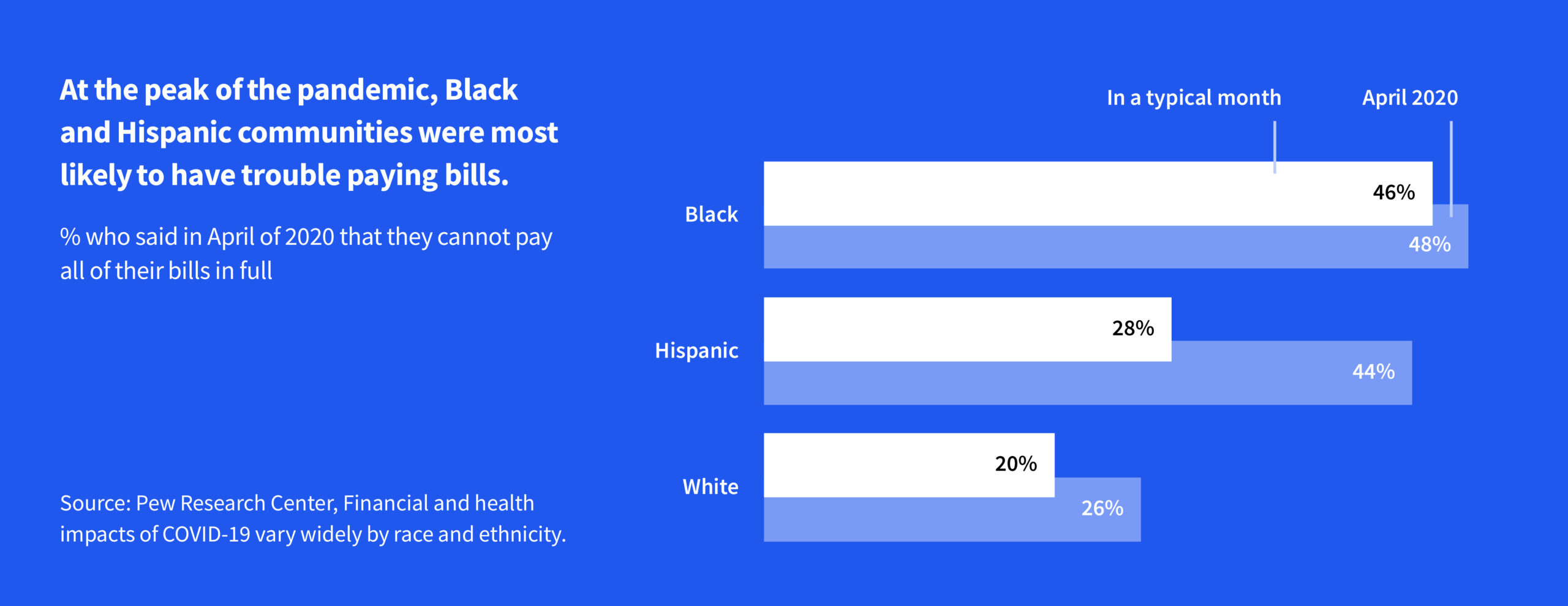

The COVID-19 pandemic both spotlighted and amplified the precarious economic situation faced by millions of Americans. It has exacted a disproportionate economic toll on those most vulnerable to economic shock due to historical government policies, namely Black, Latinx, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, Indigenous and other people of color, as well as undocumented individuals. This, at a time when more than a third of adults—and half of Black and Latinx households—did not have the cash to pay for a $400 emergency expense (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2021).

The pandemic has also provided real-time data on the ways that cash can not only provide immediate relief from financial crises, but can also bolster family incomes and prevent poverty. Complemented by cash from states, municipalities, and philanthropy, federal dollars provided unparalleled support to millions of Americans during a health pandemic that many predicted would wipe out household balance sheets.

Between pandemic stimulus checks, the expanded Child Tax Credit, and the expanded EITC, the U.S. Government provided nearly $1 trillion in direct, unrestricted cash payments to individuals (Economic Security Project [ESP], 2021). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the first two rounds of stimulus payments, enacted as part of economic relief legislation related to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, moved 11.7 million individuals out of poverty (Fox & Burns, 2021). Similarly, the first expanded Child Tax Credit payments sent in July 2021 reduced child poverty by over 40 percent, with nine out of 10 low-income families using funds to pay for basic necessities like food, clothing, rent, and utilities (Parolin et al., 2021).

At the same time, there has been a proliferation of guaranteed income pilots or demonstrations—regular, unconditional cash payments—to support low and moderate income individuals in cities and counties across the country. As of February 2022, there were an estimated 90 planned or active guaranteed income demonstrations across 21 states, including large, publicly funded pilots in Cook County, Illinois, Chicago, and Los Angeles (Stanford Basic Income Lab, n.d.a). Each responded to local needs, but all reflected a commitment to regular, unconditional cash payments that honored the agency and the unique, time-sensitive needs of recipients.

There is significant and growing evidence that direct, unconditional cash is a uniquely flexible, efficient, and swift means of addressing a range of issues funders are concerned about, including mental health (Evans and Garthwaite, 2014), physical health (McIntyre et al., 2016), children’s school achievement (Sherman et al., 2021, employment (Duncan et al., 2010), and earnings (Chetty et al., 2011) in adulthood. There has also been significant research on its impact on labor employment, poverty, economic and gender inequalities, housing mobility, and crime (Stanford Basic Income Lab, n.d.b).

This primer explains what guaranteed income is, discusses its origins and evolution, provides multiple, real-world case examples of how funders are supporting and promoting its use, and discusses related policies and how lessons learned from recent guaranteed income efforts can improve the equitable access to and efficacy of other government programs. By highlighting the critical roles that philanthropy can play in supporting guaranteed income and related cash policies, this guide is intended to support funders’ effective, impactful, and equitable investments in people and communities.

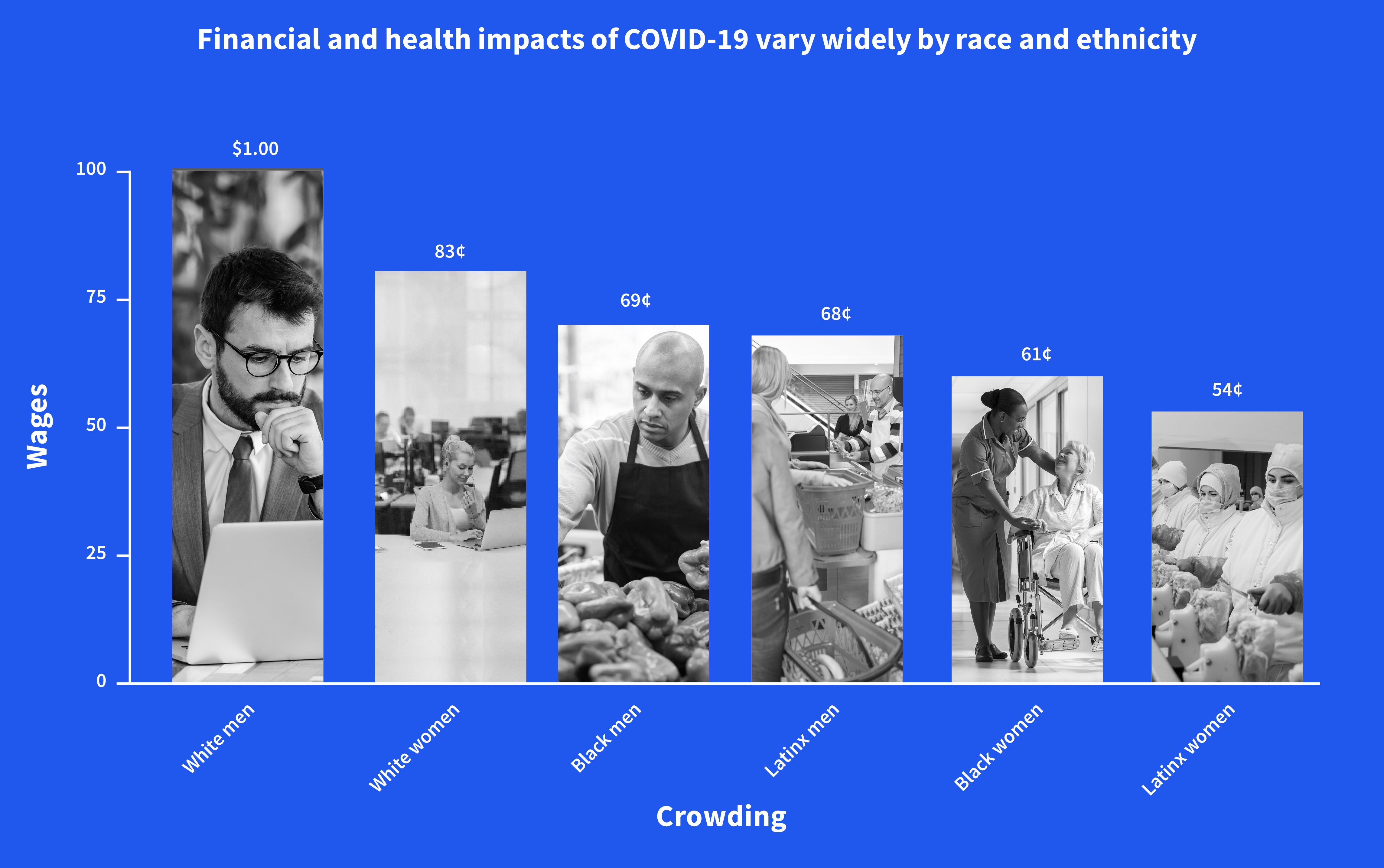

During the pandemic, essential workers with high physical proximity to customers or colleagues have faced greater health risks. Even after considering education, researchers found that white men are crowded out of essential work while Black women, Latinx women, and Latinx men are crowded into essential work. And when looking specifically at essential work with increased proximity, Black and Latinx women had the highest degree of crowding, followed by Black and Latinx men and white women, increasing their risk of illness during the pandemic. In addition, all groups earn below the average annual wages of white men, with Latinx women and Black women earning the least across essential work (54 cents and 61 cents, respectively), followed by Latinx men (68 cents), Black men (69 cents), and white women (83 cents), compared to white men ($1.00) (Hamilton et al., 2021).

Source: American Community Survey 2018 Five Year Estimates. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2020, via Building an Equitable Recovery: The Role of Race, Labor Markets, and Education.

What Is Guaranteed Income?

Guaranteed income, sometimes called guaranteed basic income or basic income, is a cash payment provided on a regular basis to members of a community with no strings attached and no work requirements. It is intended to create an income floor below which no one can fall.

While Universal Basic Income (UBI) is a regular cash payment to all members of a community, guaranteed income could be targeted or universal, but focuses on specific individuals within a community, ensuring that those with the greatest need are prioritized for assistance. In this sense, guaranteed income is comparable to existing need-based cash assistance and safety net programs. However, guaranteed income is more accessible than these programs because it comes without conditions on its use, onerous administrative exclusions based on asset limits or eligibility burdens, such as work requirements rooted historically in anti-Black racism. Guaranteed income can also reach undocumented or mixed status households, as well as formerly incarcerated people excluded from other assistance due to discriminatory federal and state policies.

Targeting can be less costly and more efficient at reaching particular groups. However, because targeted programs tend to engender more narrow constituencies, their political support tends to be equally narrow and, thus, harder to achieve and sustain. This is especially true when the policy targets people who have historically had little political power—low and moderate income people and people of color. This compounds the political challenge targeted policies face because, despite the fact that a greater absolute number of white Americans would benefit from an income-based guaranteed income program than Black or brown Americans, centuries of harmful, racialized narratives have reinforced a false perception that targeted approaches unfairly benefit undeserving Black and brown people. Research and polling suggests that race-conscious policies—those that take into account racial disparities—with a universal frame tend to draw considerably more support than race-targeted policies—those that explicitly target a particular race (Conroy & Bacon, 2020). Thus, a class-based policy approach can help strengthen political support for targeting.

Work requirements have a long history in the U.S. of contributing to racial inequities and pernicious narratives about who is deserving of assistance. Yet, many public assistance programs require recipients to demonstrate earned income or otherwise meet work requirements. In fact, the share of public assistance with such work requirements has increased in recent years (Hoynes & Whitmore Schanzenbach, 2016), leaving behind those at greatest risk of experiencing food insecurity, homelessness, and other hardships.

Visit the Center for the Study of Social Policy for more information.

On the other hand, universal programs, such as Social Security (including SSI) or universal education, are broad in scope and coverage and, thus, increase the number of people who have access to them compared to targeted programs. Because of their universal eligibility, such programs have had the greatest potential to engender and sustain broad political support. However, they often fail to address existing disparities between different groups of people. Further, since the 1970s, a retreat from progressive federal policy making, combined with deregulation and regressive taxation, have increased racial income and wealth inequality, reversing decades of progress. In this context, an important concern is that a UBI would widen the racial wealth divide if not matched with dramatic, progressive changes to the tax code. Given these trade-offs and associated tensions, targeted guaranteed income and UBI, like many proposals, can become trapped in a discussion over a universal versus targeted response.

Targeted universalism responds to the shortcomings of targeted policies that exclude many and universal policies that treat everyone equally (powell, Menendian, & Ake, 2019). Achieving equitable outcomes requires understanding how different groups perform relative to the universal goal in order to develop targeted strategies. Rather than reinforcing existing, inequitable hierarchies, targeting is intended to ensure that all benefit from a universal policy. In this sense, targeted universalism is a hybrid approach, both universal and specific, that is equitable in its result. The 2021 Child Tax Credit represented targeted universalism, despite excluding undocumented families and requiring non-tax filers to opt-in to the program. The American Rescue Plan Act, signed into law in March 2021, made the Child Tax Credit fully available to families with the lowest incomes without any work requirements, providing support to 27 million more children than were previously eligible. Given this one-year program extended eligibility to 90 percent of American families with children, it has been described as a guaranteed income for families.

Origins and Evolution of Guaranteed Income

While the idea of guaranteed income has a long and varied history dating back to Roman Times, its modern, progressive origins in the U.S. are rooted in the racial and gender justice movements of the 1960s (Bhattacharya, 2019). Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called for a guaranteed income in his final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? The Black Panther Party’s 1966 platform called on the government to guarantee everyone a job or a minimum income. The National Welfare Rights Organization, led primarily by Black mothers, argued that everyone should be guaranteed a decent standard of living as a right, regardless of whether they work for pay (Anderson & Kimberlin, 2021).

More recently, the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED)—launched in February 2019 by former Stockton, California Mayor Michael Tubbs—was the nation’s first mayor-led guaranteed income initiative. SEED gave 125 randomly selected residents from low-income neighborhoods $500 per month, with no strings attached and no work requirements, for 24 months.

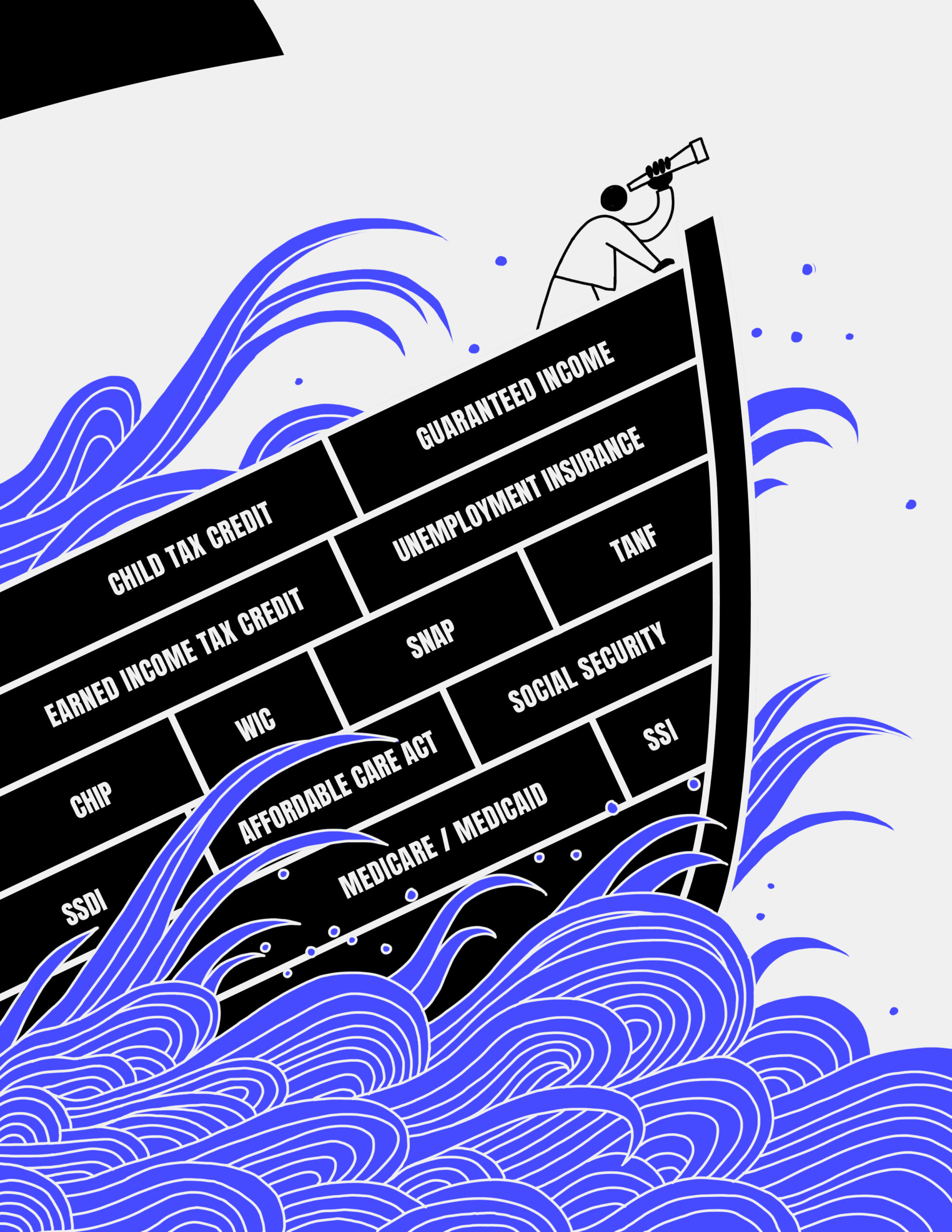

The many guaranteed income pilots that have followed SEED are recasting America’s social safety net as a public good that should not only catch one during a time of economic crisis, but also provide an economic floor below which no one can fall.

“Poverty is the biggest issue. Everything we deal with stems from that. There’s so many people working incredibly hard, and if life happens, there’s no bottom.”

– Michael Tubbs, former Stockton, CA mayor

The research team from the University of Tennessee and the University of Pennsylvania found that participation in SEED was associated with:

- Reduced income volatility—the month-to-month income fluctuations that households face: SEED participants’ income fluctuated by 46.4% monthly, while non-participants experienced a 67.5% monthly income fluctuation.

- Increased full-time employment: At the start of the demonstration, 28% of SEED participants were employed full-time; one year later, this figure had risen to 40%. Importantly, guaranteed income was not linked to a decrease in full-time employment.

- Improved health and well-being: After one year, SEED participants showed a statistically significant increase in emotional health compared to non-participants.

- Reduced depression and anxiety: SEED participants reported a lower incidence of anxiety and depressive symptoms than non-participants.

- Diminished feelings of financial scarcity and new opportunities for self-determination, choice, goal-setting and risk-taking: One participant reported that, as a result of SEED payments, his life “converted 360 degrees… because I have more time and net worth to study… to achieve my goals.” (West, Castro Baker, Samra & Coltrera, n.d.).

Convening the Field

In 2020, based on SEED’s positive impacts, narrative, and potential to influence policy, Mayor Michael Tubbs founded Mayors for a Guaranteed Income (MGI), a coalition of more than 63 mayors who believe that a guaranteed income is meant to supplement, rather than replace, the existing social safety net and can be a tool for racial and gender equity. Soon after, MGI, the Economic Security Project, Asset Funders Network, Springboard To Opportunities, Stanford Basic Income Lab, and the Center for Guaranteed Income Research launched the national Guaranteed Income Community of Practice, a community of more than 350 practitioners, policymakers, funders, researchers and advocates committed to advancing guaranteed income and related cash-based policies. Together, these initiatives have convened and coordinated the field around a set of values, principles and practices.

Why Guaranteed Income?Why Guaranteed Income?

COVID-19 spotlighted the need to rethink policies providing income supports to help all people meet their basic needs, particularly low and moderate income households most vulnerable to economic shocks. When these shocks go unaddressed and vulnerable households are left to cope without resources, they often face a devastating chain of increasingly dire events, including eviction and homelessness (Himmelstein & Desmond, 2021), bankruptcy (Weller, 2018), depression, and abuse (American Psychological Association, n.d.)—human and economic costs that exceed those of protecting against shocks in the first place.

Guaranteed income has proven a powerful response. A large and growing body of evidence demonstrates convincing impacts on economic insecurity, income, assets, physical and mental health, food insecurity, poverty, economic and gender inequalities, housing mobility, crime, early child development, and children’s school achievement, employment, and earnings in adulthood.

However, beyond a means of achieving an array of stabilizing and beneficial outcomes, guaranteed income also serves as an important general protection against a wide range of economic and noneconomic shocks. This is important because while it is crucial to prepare for specific, known threats to people’s economic security, including unemployment, it is difficult to anticipate and protect against all possible types of shocks with shock-specific programs. For example, because COVID-19 wasn’t a widely anticipated threat, a ready-made protection against it wasn’t available, leaving America to quickly invent a host of institutional responses. The COVID economic impact payments issued by federal and state governments demonstrated that unrestricted cash payments are effective at meeting critical household needs and can be disbursed swiftly at scale. If we had a robust guaranteed income program in place on an ongoing basis, we would be prepared to respond immediately and effectively to the next crisis with targeted support for those most in need.

Guaranteed income embodies an ethos of respect, trust, autonomy, dignity and freedom, ensuring individuals experience basic economic security and are able to do what is best for themselves and their families with no conditions or sanctions. It is precisely the flexibility of unrestricted money that provides individuals with agency and a way of addressing the needs they experience as most pressing in their lives. In this way, unrestricted cash assistance is swifter and more flexible and effective than in-kind assistance, such as food, clothing or even housing. That is not to say it should replace these other forms of assistance, but that it plays a critical complement to them.

The significant administrative burdens involved in accessing public benefits — lengthy applications, long wait times, onerous documentation requests, gaps, delays and inadequate support — exact a painful and costly ‘time tax’ on low and moderate income people. The significant time, psychological effort and aggravation required create a critical barrier to equitable access for those who need assistance the most, but often give up trying (Pugh et al., 2022). By contrast, guaranteed income provides a respectful, flexible, effective approach to close gaps and improve equity and access while we improve existing benefits.

StrategiesStrategies for Philanthropy

While guaranteed income is often considered a regular cash payment made by the government, philanthropic funders are playing a strategic role in advancing this evidence-based solution. This section outlines several real-world examples of ways philanthropic funders have supported and advanced the use of guaranteed income. The examples span four ‘philanthropic plays’ or major strategies used by funders to advance positive social change: direct service, system and capacity building, policy and advocacy, and research and innovation (The Center for High Impact Philanthropy, n.d.).

In addition to serving clients, direct service tests and refines what a scaled-up program could look like. System and capacity building build the broader field. Policy and advocacy build the longer-term political viability of cash-based policies. Research and innovation strengthen the case for cash by building needed evidence and defining new models and practices. All are strategic investments necessary to achieving impact and scale.

A. Direct Service

Philanthropy has played an early and central role in funding direct guaranteed income cash payments to low and moderate income individuals, including SEED (the Stockton, California pilot that catalyzed a wave of mayor-led guaranteed income demonstrations) and the Magnolia Mother’s Trust program in Jackson, Mississippi (one of the longest running guaranteed income demonstrations and the first to center Black moms). Such funding has been particularly important for pilots demonstrating the power of unconditional cash in the lives of vulnerable individuals. And critical to the success of these early demonstrations has been an emphasis on centering community voice in their design.

Funding Spotlight

Context

Formerly incarcerated people face disproportionate financial challenges exiting the criminal justice system, including finding stable jobs and housing, paying fines and fees to avoid re-incarceration, and investing in education and training (Economic Security Project, 2022).

Spotlight

Gainesville, Florida-based Community Spring launched the Just Income GNV guaranteed income pilot in Alachua County, Florida to provide unconditional monthly payments directly to those who have been impacted by the justice system. Designed and administered by formerly incarcerated people, the Florida demonstration is an important test of the impact guaranteed income can have on some of the most vulnerable members of society at a moment when guaranteed income and re-entry support are gaining momentum.

Funders

Spring Point Partners; Mayors for a Guaranteed Income

B. System and Capacity Building

Philanthropy is playing a significant role in building the growing field of funders, practitioners, researchers, and advocates focused on guaranteed income and related cash policies.

The Just Futures Fund is a comprehensive policy proposal conceived to simultaneously address income insecurity and low wealth, with a particular focus on racial equity (Shapiro et al., 2020). It combines guaranteed income with contributions to “baby bond” accounts meant to build substantial wealth for children from low-wealth families.

- A $1,000 per month guaranteed income for each adult, along with a $250 payment per month, per child, would dramatically lower the poverty rate, most noticeably for people of color, and eliminate poverty for other key groups.

- “Kids’ Futures Accounts” would significantly increase

the wealth of families of color and reduce the racial

wealth gap.

Funding Spotlight

Context

Since 2019, the number of individuals who have learned of, grown interested in, and devoted some or all of their professional attention to guaranteed income has exploded. This new interest has provided an opportunity to onboard and educate the growing number of policy experts, researchers, community and program leaders, funders, and elected officials on the potential and simplicity of recurring, unconditional cash.

Spotlight

The national Guaranteed Income Community of Practice convenes guaranteed income stakeholders to promote learning and collaboration and to develop best practices for policy making. Building on the success of the Magnolia Mother’s Trust, the first prominent community-based guaranteed income pilot, and SEED, the first mayor-led guaranteed income demonstration, the Guaranteed Income Community of Practice provides a learning platform to grow and support the diverse stakeholders working to advance guaranteed income.

Philanthropic funding enabled the Economic Security Project and its co-convenors, Springboard To Opportunities, Stanford Basic Income Lab, Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, Center for Guaranteed Income Research, and the Asset Funders Network, to put in place the staffing, governance, and online infrastructure to host and foster an active community of practice of more than 350 participants. There are also statewide communities of practice in different parts of the U.S., including California, Illinois, and Virginia, which provide members a forum to learn from and support local pilots and state policy.

Funders

The Kresge Foundation; Economic Security Project; an anonymous donor

Funding Spotlight

Context

The radical ideas of one generation often become the common sense of the next. Some of the most important progressive policies of America’s modern era that we now take for granted were possible because they were supported by broad grassroots movements. These movements are built by people and campaigns, social justice coalitions, culturemakers, committed volunteers and lawmakers. So, while guaranteed income communities of practice are defining, equity-focused principles and practices, activists are building the social and political capital necessary to win changes in state and federal policy, including important reforms to related cash policies. Philanthropy is playing a significant role in building the growing field of funders, practitioners, researchers, and advocates focused on guaranteed income and related cash policies. It is also supporting important narrative change that reinforces effective policy and advocacy.

Spotlight

Income Movement is an inclusive, people-powered movement on a mission to build an economy that works for everyone. The concept of guaranteed income has begun to move from radical to practical at a rapid pace, with progress fueled in large part by the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic fallout. Income Movement is meeting this moment by supporting grassroots organizers, increasing awareness and educating the public about guaranteed income, organizing direct actions to apply pressure to elected officials, and coordinating diverse coalitions as they build towards the goal of an income floor for all by the year 2030.

Funders

The Ellis Family Charitable Foundation; Purdy Family Foundation

Funding Spotlight

Context

Expanded unemployment benefits, stimulus checks, and the expanded Child Tax Credit provided further evidence to contradict the racialized narrative that cash assistance reduces the incentive to find a job. However, this narrative persists among policymakers and those living in poverty socialized to understand they are poor because they’re not smart or hard working enough.

Spotlight

Jackson, Mississippi-based Springboard To Opportunities partnered with Ms. Magazine (Perry Abello, 2021) to host narrative change journalism that challenged pernicious racialized narratives about who is worthy and deserving of cash assistance. For example, in a powerful first-person commentary called “A Little Push,” Tia, a Black mom of three previously experiencing extreme poverty, recounts how receiving $1,000 per month for 12 months changed her life, allowing her to better care for the health and basic needs of herself and her children, see her father for the first time in 20 years, and afford a house.

Funders

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Kresge Foundation; Battery Powered

C. Policy and Advocacy

Philanthropy is increasingly acknowledging the importance of addressing the lasting impacts of systemic racism and the forces underlying volatility and insecurity among workers across the U.S. Building on guaranteed income is a compelling policy change investment needing local, state, and federal advocacy. This can include policy changes to expand direct, unconditional cash payments to individuals, and policy changes to apply lessons learned from guaranteed income to improve access to and design of other public policies (Anderson & Kimberlin, 2021).

Funding Spotlight

Context

While top Massachusetts earners saw their wages surge in recent years, low and moderate income households—disproportionately people of color—saw relatively little gain. This, during a period in which the cost of housing and child care, among other essential expenses, have outpaced what many can afford. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated economic insecurity as it created job losses, especially for low-income workers and workers of color. Federal Economic Impact Payments (stimulus checks) and expanded Unemployment Insurance mitigated the economic pain, but ran out before many were back on their feet, and these cash supports excluded undocumented individuals and those exiting the justice system. Recognizing these challenges, local and state governments have taken action to support their residents. Some of these efforts have gone beyond short-term pandemic relief to provide more sustained assistance.

Spotlight

Advocates in Massachusetts looked to the state EITC as an area where cash assistance could be expanded. In response, Boston Indicators—the research center at the Boston Foundation—partnered with the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center and Economic Security Project to produce “A Guaranteed Income for Massachusetts.” This report advocated for five big reforms to the state’s EITC to enable it to function more like a guaranteed income for Massachusetts residents. Taken together, these reforms would provide all families earning up to $70,000 a credit of at least $1,200 a year (and often much more), and would cover households with no income at all who are currently excluded from the state EITC.

Funders

The Boston Foundation; Economic Security Project

D. Research and Innovation

Philanthropy is playing an important role supporting research that helps answer essential questions and innovation that drives new practices. In addition to helping answer questions about guaranteed income’s impact in such areas as mental health, goal-setting, and individuals’ ability to cope with financial shocks, philanthropy is helping answer broader policy questions, such as:

- Who does guaranteed income work best for and how?

- What payment amount creates change in a given area?

And is the relationship between amount and impact linear? - What impact does frequency of payments have?

- How does guaranteed income interact with local existing policies, benefits and labor markets?

- What infrastructure is required to scale a guaranteed income program?

Funding Spotlight

Context

Although cash is one of the most researched topics across the developing world, until recently, there’s been relatively little evidence for the benefits of unconditional cash in developed countries like the U.S.

Spotlight

The Center for Guaranteed Income Research (CGIR) at the University of Pennsylvania is an applied research center specializing in cash-transfer research, evaluation, pilot design, and narrative change. CGIR provides mixed-methods expertise in designing and executing empirical guaranteed income studies that work alongside the existing safety net. CGIR was established following the evaluation of SEED, which demonstrated a new, more inclusive way of thinking about and implementing research and evaluation of guaranteed income. This included working closely with community-based organizations and government stakeholders and involving guaranteed income participants in the design of the evaluation process.

Funder

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Guaranteed income is a bold policy with a long history that has started to shift America’s perception of the social safety net in ways that were unimaginable even five years ago. The pandemic may have moved this shift into overdrive, but a health and economic crisis alone isn’t why we need a guaranteed income. If we want to create a more just safety net and a more resilient economy and country, a guaranteed income is that public good. Philanthropy has a critical role to play in getting us there, helping test guaranteed income policies, answer outstanding questions, build the field for progressive change, challenge harmful, racialized narratives about deservingness, and advocate for guaranteed income policy centered on security, equity and dignity.

Related Cash PoliciesRelated Cash Policies

In addition to supporting guaranteed income in the key areas outlined above, funders are playing a critical role supporting reform and expansion of existing cash-based government policies, including the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit, and similar state-level refundable tax credits. For example, funders are supporting outreach to help people claim CTC and EITC credits, advocacy to expand these programs and stakeholder collaboration, such as the Automatic Benefits for Children (ABC) Coalition, to advance these policies.

A. Earned Income Tax Credit

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a refundable tax credit for low and moderate income workers provided by the Federal Government and more than half of state governments. The current EITC is worth up to $6,728 in refundable cash based on income level, family size and marital status. Though expanded in 2021, the EITC requires earned income sufficient to attain the full credit and provides relatively little to workers without minor children at home. Thirty years of evidence on EITC policy expansions has confirmed that the EITC is one of the most effective anti-poverty programs in the United States (Bastian & Jones, 2019), increasing average annual earnings, labor supply, and payroll and sales taxes paid. As of December 2021, 25 million workers and families received approximately $60 billion in EITC averaging $2,411 (U.S. Internal Revenue Service, n.d.). Advocates around the country are working to expand state EITC policies to provide more generous benefits, include childless workers and immigrants who file taxes with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN), to be fully refundable, and require no earned income to claim the full benefit.

“Child checks took the fear of my children experiencing food insecurity away. I was able to provide nutritious food for them throughout the month bc of the child checks. It meant everything to our family.”

— Karese, NC (Parents Together Action, 2022)

B. Child Tax Credit

The Child Tax Credit (CTC) provides low and moderate income parents with a tax credit for each dependent child. In 2021, the CTC was temporarily expanded until the end of the year as a part of the American Rescue Plan Act, which made the credit fully refundable, available to parents with little or no earned income and distributed on a monthly basis rather than as a lump sum after filing taxes. This expanded version of the CTC, available to 39 million households representing 88% of children in the U.S., aligned much more closely to child allowance programs in other countries. Columbia University estimated that the first installment of the Child Tax Credit in 2021 lifted three million kids out of poverty, representing a 25% cut in the monthly child poverty rate from 15.8% to 11.9% (Parolin et al., 2021). Although this important change to the program was only extended for one year, it demonstrated the ways in which unconditional cash could be deployed swiftly to meet children’s basic needs. Advocates continue to work to make permanent these expansions in federal law, and to expand state CTC programs.

Lessons LearnedHow Lessons from Guaranteed Income Can Improve Other Programs

In addition to supporting expansion of existing cash-based policies, there are opportunities to reform other public policies by applying guaranteed income principles that streamline access and remove onerous or inequitable requirements (Anderson & Kimberlin, 2021). For example, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, temporary changes were made to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Medicaid that reduced paperwork, office visits and work requirements, all of which increased access to critical assistance. Likewise, simplifying eligibility for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) could speed cash assistance to aged, blind and disabled people who have little or no income. Improving data sharing and coordinating eligibility and application processes across benefits systems would likewise streamline access to needed resources. Some of these changes can be made by state and local policymakers, while others (especially SSI, SNAP, and Medicaid) would require action by federal policymakers.

Resources

Guaranteed Income Community of Practice Resources

Basic Income evidence visualization

Q&A: Understanding Guaranteed Income & Safety Net Support for Californians

Q&A: Implementing Guaranteed Income Through Cash and a Strong Safety Net

References

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). What the economic downturn means for children, youth and families. https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/economy

Anderson, A. & Kimberlin, S. (2021). Q&A: Understanding guaranteed income & safety net support for Californians. California Budget & Policy Center. https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/qa-understanding-guaranteed-income-safety-net-support-for-californians/

Bastian, J. E., & Jones, M. R. (2019). Do EITC expansions pay for themselves? Effects on tax revenue and public assistance spending. Journal of Public Economics, 196, 10455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104355

Bhattacharya, J. (2019). Exploring guaranteed income through a racial and gender justice lens. Roosevelt Institute. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/RI_UBI-Racial-Gender-Justice-brief-201906.pdf

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2021). Economic well-being of U.S. households in 2020. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2020-report-economic-well-being-us-households-202105.pdf

The Center for High Impact Philanthropy. (n.d.). Four philanthropic plays: How philanthropy can help. https://www.impact.upenn.edu/four-philanthropic-plays-how-philanthropy-can-help/

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., & Rockoff, J. (2011, November). New Evidence on the Long-Term Impacts of Tax Credits. Proceedings. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association, 104, 116‒124. http://www.jstor.org/stable/prancotamamnta.104.116

Conroy, M. & Bacon, Jr., P. (2020, July 14). White Democrats are

wary of big ideas to address racial inequality. FiveThirtyEight.

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/white-democrats-are-wary-of-big-ideas-to-address-racial-inequality

Duncan, G. J., Ziol-Guest, K. M., & Kalil, A. (2010). Early-childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior, and health. Child Development, 81(1), 306‒325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01396.x

Economic Security Project. (2021, April). The COVID recession and the year of checks. https://www.economicsecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-COVID-Recession-and-the-Year-of-Checks.pdf

Economic Security Project. (2022, March 20). Just Income GNV. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Xb6yyxo6WGg

Evans, W. N., & Garthwaite, C. L. (2014). Giving Mom a break: The impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(2), 258‒290. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.6.2.258

Fox, L. E. & Burns, K. (2021, September). The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2020 current population reports. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-275.pdf

Hamilton, D., Biu, O., Famighetti, C., Green, A. V., Strickland, K., & Wilcox, D. (2021). Building an equitable recovery: The role of race, labor markets, and education. The New School Institute on Race and Political Economy. https://www.newschool.edu/institute-race-political-economy/Building_An_Equitable_Recovery_Hamilton_et_al_2021.pdf

Himmelstein, G. & Desmond, M. (2021, April 1). Eviction and health: A vicious cycle exacerbated by a pandemic. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20210315.747908/full/

Hoynes, H. W. & Whitmore Schanzenbach, D. (2018). Safety net investments in children (NBER Working Paper No. 24594). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w24594

Mcintyre, L., Kwok, C., Emery, J., & Dutton, D. J. (2016). Impact of a guaranteed annual income program on Canadian seniors’ physical, mental and functional health. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 107(2), e176–e182. doi:10.17269/cjph.107.5372

Parents Together Action. (2022, February 10). New survey reveals rising family poverty and child hunger as second month without the expanded child tax credit approaches.

Parolin, Z., Collyer, S., Curran M. A., & Wimer, C. (2021). Monthly poverty rates among children after expansion of the Child Tax Credit. Poverty and Social Policy Brief, 5(4). https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/s/Monthly-Poverty-with-CTC-July-CPSP-2021.pdf

Perry Abello, O. (2021, April 1). Guaranteed income in Mississippi designed by Black moms for Black moms, showing results for Black moms. Ms. Magazine. https://msmagazine.com/2021/04/01/guaranteed-income-jackson-mississippi-black-moms-magnolia-mothers-trust

Pugh, J., Kline, S., Olle, T., & Chávez Quezada, E. The Troubling Gap Between What’s Offered by Our Social Safety Net and What’s Received. In These Times. April 19, 2022. https://inthesetimes.com/article/social-safety-net-economy-welfare

powell, j. a., Menendian, S., & Ake, W. (2019, May). Targeted universalism: Policy & practice. Othering & Belonging Institute. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/targeted-universalism

Shapiro, T., Meschede, T., Pugh, J., Morgan J., & Stewart, S. (2020, April). Accelerating racial equity and justice: Basic income and generational wealth. Waltham Institute on Assets and Social Policy. https://heller.brandeis.edu/iere/pdfs/racial-wealth-equity/racial-wealth-gap/accelerating-equity-and-justice.pdf

Sherman, A., Safawi, A., Neuberger, Z., & Fischer, W. (2021, August 5). Recovery proposals adopt proven approaches to reducing poverty, increasing social mobility. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/recovery-proposals-adopt-proven-approaches-to-reducing-poverty

Stanford Basic Income Lab. (n.d.a). Map of universal basic income experiments and related programs. https://basicincome.stanford.edu/experiments-map

Stanford Basic Income Lab. (n.d.b). Visualizing UBI research.

https://basicincome.stanford.edu/research/ubi-visualization/

U.S. Internal Revenue Service. (n.d.) Statistics for tax returns with the earned income tax credit (EITC). https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-the-earned-income

Weller, C. (2018, July 26). Working-class families are getting hit from all sides. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/working-class-families-getting-hit-sides/

West, S., Castro Baker, A., Samra, S. & Coltrera, E. (n.d.) Preliminary analysis: SEED’s first year. Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration. https://www.stocktondemonstration.org/s/SEED_Preliminary-Analysis-SEEDs-First-Year_Final-Report_Individual-Pages.pdf