Free and Simplified Tax Filing

Removing Barriers to Tax Filing for Independent Contractors

08. 27. 2025

What lawmakers can do to ensure that more independent contractors can claim important benefits.

Over the past 15 years, new technologies have emerged that connect workers to jobs on a short-term, on-demand basis, a model that relies on online marketplaces such as Uber or TaskRabbit to link clients and workers. The rise of “platform” or “gig” work has focused attention on a set of long-standing challenges facing non-traditional workers—workers whose earnings derive from sources outside a traditional employer-employee relationship. These challenges include access to benefits—such as those delivered through the tax code—and ensuring that workers pay the taxes they legally owe.

Data from an in-depth study of California tax returns showed that nearly one of every five California workers relied, in whole or in part, on earnings as an independent contractor in 2016. Independent contractors—workers who are considered self-employed for tax purposes—face special challenges when filing their tax returns. Unlike traditional wage and salary workers, who have taxes withheld from their paychecks throughout the year, independent contractors’ taxes are not subject to withholding, and many do not receive basic reports—called information returns—detailing amounts they earned to use when filing their taxes. Additionally, many low- and middle-income workers, particularly those who may not think of themselves as “small businesses,” do not fully understand their tax obligations. And while there are services designed to assist lower-income households prepare and file a tax return, support for the self-employed is more limited. The Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) program, for example, does not prepare returns claiming common expenses incurred by the self-employed, such as home office or depreciation deductions. Nor are they eligible for Direct File, the IRS’s free, public filing portal. This complexity, coupled with limited access to existing supports, forces many independent contractors to rely on costly private tax preparers, and some even forego filing an accurate return, as evidenced by the high rates of noncompliance among the independent contractor workforce.

This brief explores options for expanding tax filing assistance to independent contractors. It begins by profiling the independent contractor workforce, with a particular focus on California, and examines the challenges they face when filing their tax returns. It concludes with a set of recommendations aimed at easing these challenges with the goal of reducing the complexity and cost of filing a tax return, ensuring access to income supports provided through the tax code, and improving tax compliance.

The Gig WorkforceThe Independent Contractor Workforce

Key Takeaways

While nearly 1 in 5 California workers received at least some income from independent contracting in 2016, those earnings accounted for only 3.0 percent of total compensation paid in the state that year.

California workers who derived all of their 2016 income from independent contracting were twice as likely to be among the lowest-income workers in the state as compared to those whose earnings came from traditional wage and salary employment.

Nationally, the independent contractor workforce was more likely to be older male; white or Latino; to work part-time; and to be self-employed than the workforce as a whole.

Nationally, platform workers were more likely to be young, single, and male than non-platform independent contractors in 2016.

Despite substantial media attention over the past decade, platform work still makes up a very small share of the workforce with only 1.4 percent of the Californians included in the UC Berkeley study of 2016 tax filers receiving income from platform work.

Among California’s independent contractors, platform workers were much more likely to use earnings from platform work to supplement wages and salaries than were other independent contractors.

Independent contractors differ from employees in a number of important ways, including how their earnings are reported for tax purposes; by the fact that they do not receive health or retirement benefits from an employer; that they are not covered by unemployment insurance or other payroll-tax based social insurance programs; and because they must pay self-employment taxes at a rate equivalent to that paid by both the employer and employee towards Medicare and Social Security. Wage and salary employees have their earnings for tax purposes reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and to them, on a W-2. Many, but not all, independent contractors have their earnings reported to the IRS, and to them, on a form 1099 (see below), and this brief will use the term “1099 worker” interchangeably with “independent contractor.” Independent contractors are also sometimes referred to as sole proprietors by virtue of operating their own unincorporated business. Researchers at the UC Berkeley Labor Center and California Policy Lab identify three categories of independent contractors based on whether and how their income is reported in tax filings:

- Traditional 1099 workers: These are workers who provide services to non-platform businesses and who receive 1099 forms reporting their earnings as non-employee compensation. Examples of traditional 1099 workers include professional service providers, such as bookkeepers or accountants, performing artists, graphic designers, and freelance consultants. In 2016, traditional 1099 workers accounted for 4.8 percent of the California workforce studied by the Berkeley researchers.

- Platform 1099 workers: These are independent contractors whose earnings are intermediated by online on-demand labor platforms, such as Uber, DoorDash, or TaskRabbit. As detailed below, platforms are required to report payments to contractors that reach certain thresholds. In 2016, platform 1099 workers accounted for 1.4 percent of the California workforce studied, and the researchers note that this figure is consistent with other more recent estimates of the prevalence of platform work.

- Non-1099 contractors: These are independent contractors who provide services directly to consumers or who sell goods directly to businesses or consumers without intermediation through a platform do not receive a 1099 but are still required to file tax returns and report their earnings for tax purposes. This category of work includes a range of occupations such as child or eldercare providers, housekeepers, home repair people, and haircutters who work directly for their client. Workers who don’t receive a 1099 accounted for the largest share of California’s independent contractors in 2016, 12.1 percent of the workforce studied by the Berkeley researchers.

While many experts argue that a large share of the contractor workforce should more properly be considered employees, issues of misclassification are beyond the scope of this report. Instead, this brief will assume that independent contractors have been appropriately classified and that their earnings must be reported as income from self-employment for tax purposes.

The Gig Workforce

The term “gig worker” is used to describe a variety of work arrangements that fall outside of the traditional employer-employee relationship. It is often associated with work mediated through online platforms, such as rideshare companies. The term has no formal meaning for tax purposes and, in fact, can be misleading since workers’ earnings are considered business income, rather than wages. This brief follows the taxonomy described above and uses the term “platform worker” for earnings mediated through online marketplaces.

Moreover, independent contractors—including platform workers—are different, and are subject to different tax filing requirements, than other forms of contingent workers, such as those working on-call, for temporary help agencies, or those that are employed as traditional employees by contract labor firms. In each of these arrangements, workers are legally considered employees of the agency or firm that hires them and report their earnings as wage or salary income.

While the rise of platform-based work has received considerable attention, platform workers account for a small share of independent contractors, both in the nation as a whole and in California, with 1.4 percent of 2016 California workers receiving earnings from platform work and with platform workers accounting for 7.7 percent of workers engaged in independent contracting.

A National Snapshot

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) most recent survey of the contingent workforce estimated that 11.9 million people nationally—7.4 percent of total employment—worked as an independent contractor as their sole or primary form of employment in July 2023, up from 6.9 percent of total employment in May 2017. An additional 1.9 million persons worked as an independent contractor as a second or non-primary job. The BLS data show that independent contractors were:

- More likely to be aged 55 and older, with 11.5 percent of workers in that age group working as independent contractors as their sole or primary job as compared to 6.9 percent of those ages 25-54, and 2.2 percent of those ages 16-24.

- More likely to be male, with 8.7 percent of men employed as independent contractors as compared to 5.8 percent of women.

- More likely to be White or Latino, with 7.9 percent and 7.4 percent working as independent contractors respectively. By contrast, 5.4 percent each of Black and Asian workers were independent contractors.

- More likely to work part-time, with 13.1 percent of part-time workers working as independent contractors versus 6.2 percent of the full-time workforce.

- Likely to be self-employed, with 84.6 percent of independent contractors self-employed. Notably, not all self-employed workers were independent contractors. The BLS considers individuals who report being self-employed at “incorporated” businesses to be wage and salary workers, since legally they are employed by the business that they own.

The likelihood of working as an independent contractor was highest among those reporting an occupation in the arts, design, entertainment, sports, or media (28.1 percent); personal care and services (19.7 percent); construction and extraction (15.1 percent); and building and grounds maintenance and cleaning (13.2 percent). Independent contractors were most prevalent in real estate and rental and leasing (24.2 percent of the workforce) and construction (18.5 percent).

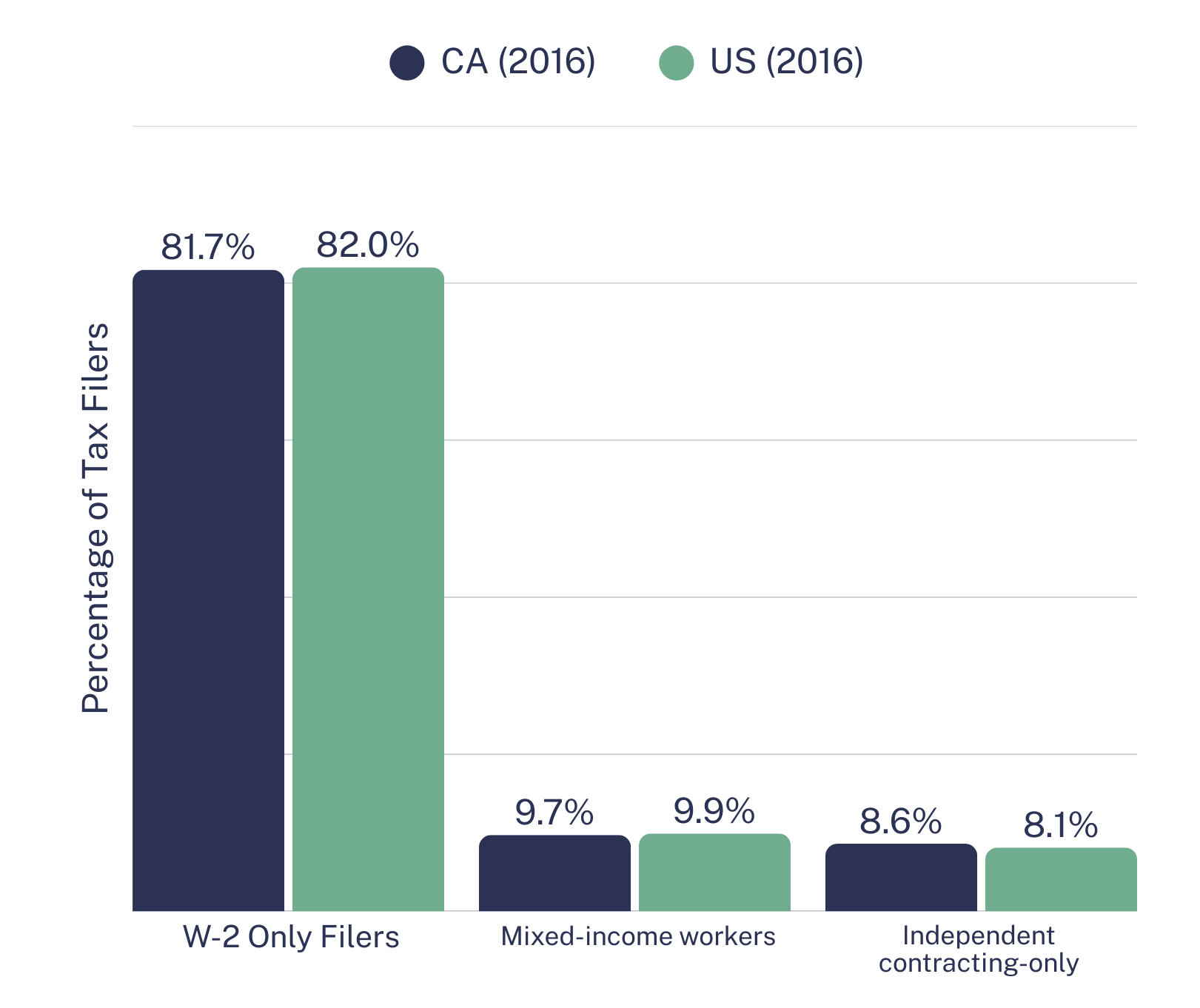

Research based on federal tax data finds that slightly less than one out of five workers filing a 2016 tax return either combined income from wages and salaries with that from self-employment or only reported earnings from self-employment (Figure 2).

Figure 2: About One Out of Five Taxfilers Received Some or All of Their Income from Independent Contracting, 2016

Sources: UC Berkeley Labor Center/California Policy Lab and author’s calculations from Internal Revenue Service.

Annette Bernhardt, et al, “Independent Contracting in California: An Analysis of Trends and Characteristics Using Tax Data” (March 2022) downloaded from https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Independent-Contracting-in-CA.pdf; and Brett Collins, et al, “Is Gig Work Replacing Traditional Employment? Evidence from Two Decades of Tax Returns (March 25, 2019) downloaded from https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/19rpgigworkreplacingtraditionalemployment.pdf.

Platform work has emerged as a way for workers to supplement income from traditional employment. While platform workers—workers with earnings from on-demand labor platforms such as Uber, Lyft, or Doordash—still account for a relatively small fraction of independent contractors, researchers find that platform-mediated work has increased significantly as a share of the workforce receiving a 1099. The same researchers find that this growth was driven by workers with mixed sources of income—that is, workers whose primary source of employment was a traditional job and who supplemented those earnings with platform work. Significantly, the platform workforce looked different than non-platform independent contractors, with platform workers more likely to be young, single, and male than non-platform 1099 workers. The platform workforce is also more concentrated in large urban centers relative to the workforce as a whole. Lastly, researchers find that most of the growth in the platform workforce came from people reporting relatively small amounts of earnings from independent contracting as a supplement to wage and salary income.

A California Deep Dive

Research based on three years of California tax return data provides a detailed look at the state’s independent contractor workforce. In 2016, nearly one in five of the state’s workers—2.72 million tax filers—relied in whole or in part on earnings as an independent contractor; 8.6 percent (1.28 million) relied solely on earnings as an independent contractor, and 9.7 percent (1.44 million) combined wage and salary earnings with those from independent contracting. These figures are roughly consistent with the nation as a whole (Figure 2).

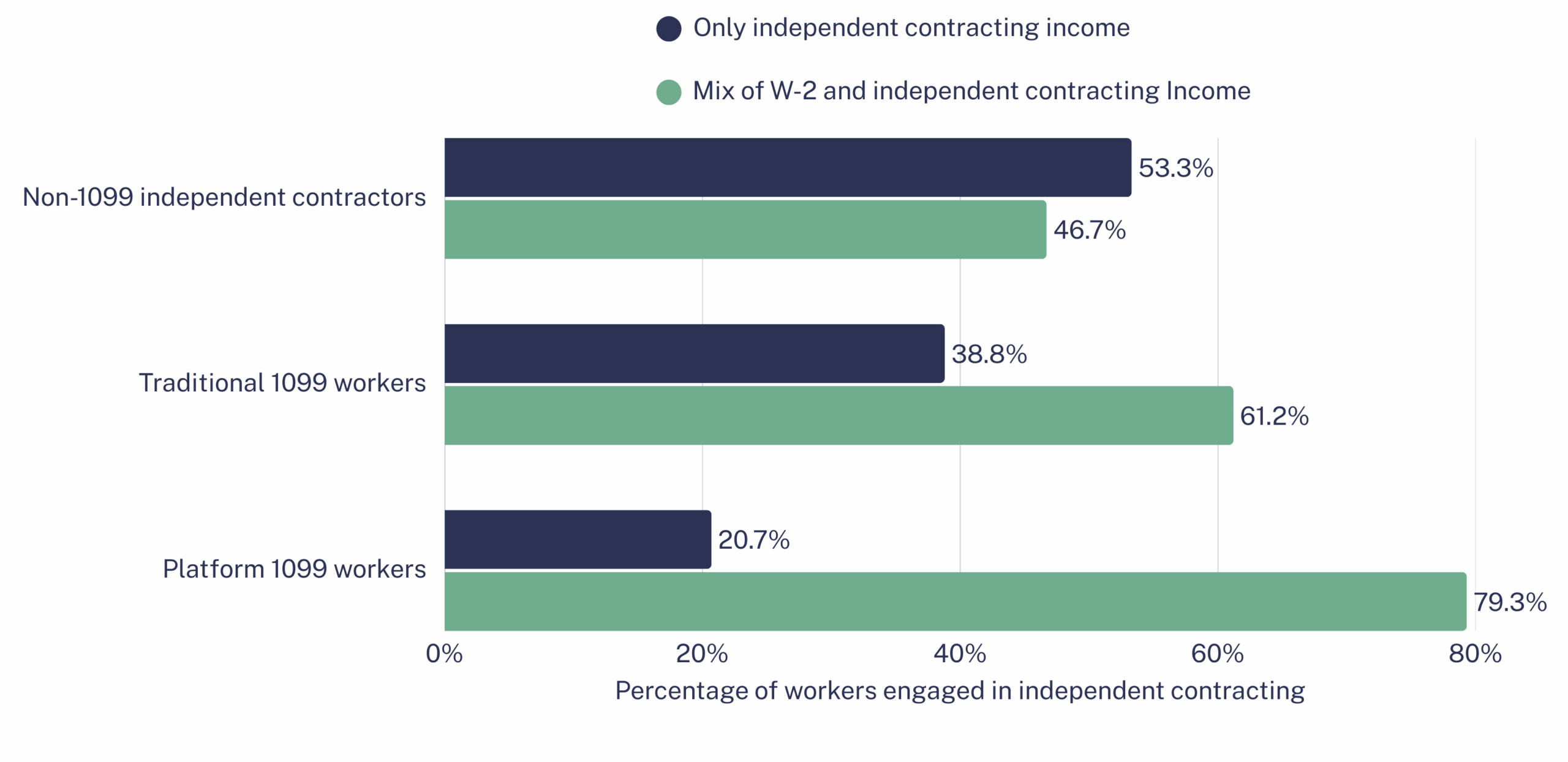

Among independent contractors, platform workers were most likely to combine income from wages with that from self-employment, while non-1099 workers—those who provide goods or services directly to individuals—were mostly likely to have independent contracting as a sole source of income (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Types of Independent Contracting and Sources of Earned Income in California, 2016

Source: Annette Bernhardt, et al, “Independent Contracting in California: An Analysis of Trends and Characteristics Using Tax Data” (March 2022) downloaded from https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Independent-Contracting-in-CA.pdf.

Even though one in five workers has some earnings from independent contracting, those earnings accounted for a very small share of total compensation paid by California firms to state residents in 2016—3.0 percent. The same study found that workers whose only earnings came from contracting were just over twice as likely to be poor as the workforce as a whole, with 51 percent having household incomes in the lowest quartile of the distribution as compared to 25 percent for all workers (Figure 4). By contrast, workers who mixed wage and salary income with that from self-employment were distributed fairly evenly across the income distribution.

Figure 4: Demographics of California workers, by type of work, 2016

| W2-only workers | Mixed-income workers | Independent contracting-only workers | All workers | ||

| Age | |||||

| 18-25 | 17.7% | 12.6% | 5.0% | 16.1% | |

| 26-40 | 34.8% | 37.8% | 25.7% | 34.3% | |

| 41-55 | 29.9% | 31.9% | 34.4% | 30.5% | |

| 56-64 | 13.1% | 12.8% | 19.4% | 13.6% | |

| 65-80 | 4.5% | 4.9% | 15.5% | 5.5% | |

| Tax filing status | |||||

| Single | 52.2% | 51.3% | 41.4% | 51.2% | |

| Married | 47.8% | 48.7% | 58.6% | 48.8% | |

| Region | |||||

| Los Angeles Metro Area | 40.9% | 47.2% | 48.3% | 42.2% | |

| San Francisco Metro Area | 14.9% | 16.0% | 13.9% | 14.9% | |

| San Diego Metro Area | 8.7% | 8.5% | 8.1% | 8.6% | |

| Rest of CA | 35.5% | 28.3% | 29.7% | 34.3% | |

| Adjusted household income (scaled to household size) | |||||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 22.1% | 25.9% | 51.0% | 25.0% | |

| 2nd quartile | 25.9% | 23.6% | 18.5% | 25.0% | |

| 3rd quartile | 26.1% | 24.6% | 15.1% | 25.0% | |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 25.9% | 26.0% | 15.4% | 25.0% |

Source: Annette Bernhardt, et al, “Independent Contracting in California: An Analysis of Trends and Characteristics Using Tax Data” (March 2022) downloaded from https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Independent-Contracting-in-CA.pdf.

Taken as a whole, California’s independent contractor workforce looks similar to that of the nation, with workers reporting only earnings from contracting or from both traditional employment and independent contracting more likely to be disproportionately represented in construction; transportation and warehousing; real estate and rental leasing; professional services; and arts, entertainment, and recreation. Workers whose only reported 2016 income came from independent contracting were also more likely to be married (Figure 4). Older workers were also much more likely to receive earnings from independent contracting in 2016 than were younger workers, with the lowest-income seniors most likely to have all their employment-related earnings coming from independent contracting, while higher-income seniors were more likely to have wage and salary income or a mix of earnings from wages and contracting.

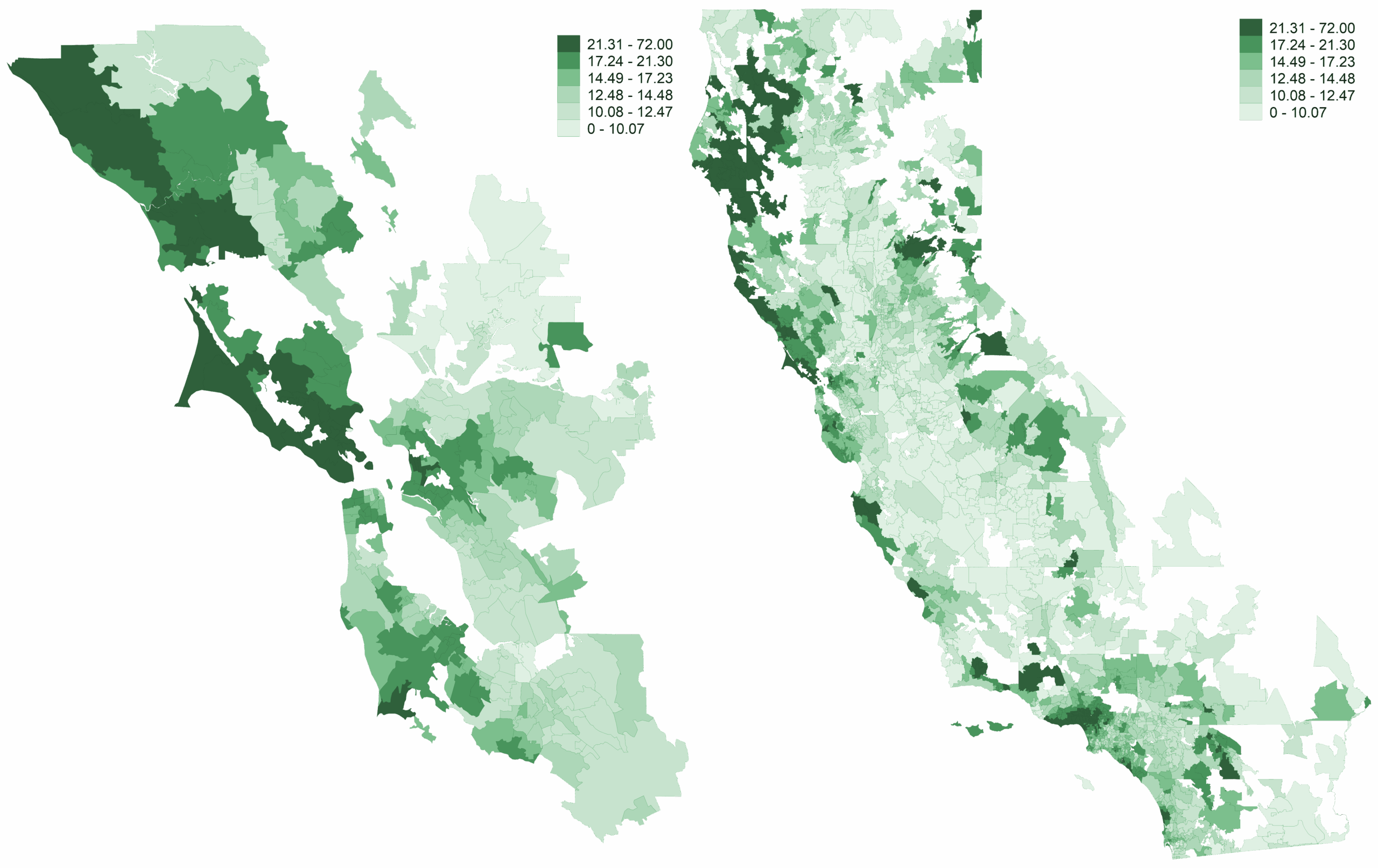

Independent contractors were overrepresented in the Los Angeles Metro Area workforce and underrepresented outside the coastal metro areas (Figure 4). The San Francisco Bay Area is home to the second-highest concentration of independent contractors. The region’s shares of workers whose sole source of income comes from contracting (13.9 percent) and workers with a combination of earnings from independent contracting and wage and salary work (16.0 percent) are roughly proportional to the share of all California workers who live in the San Francisco Metro Area (14.9 percent). Interestingly, independent contracting is more prevalent in higher-income zip codes, but less common among higher income workers and families.

Figure 5: Share of Workers with Independent Contractor Income by Zip Code, 2016

Source: Bernhardt, A., Campos, C., Prohofsky, A., Ramesh, A., & Rothstein, J. (2023). Independent Contracting, Self-Employment, and Gig Work: Evidence from California Tax Data. ILR Review, 76(2), 357-386 downloaded from https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939221130322.

Platform Work in California

The platform workforce differs from the independent contractor workforce as a whole in a number of key respects. California’s platform workforce constituted a relatively small share of tax filers—1.4 percent—in 2016. Most significantly, six out of ten—59.3 percent—worked in transit and ground passenger transportation. While researchers found little evidence of an increase in the overall prevalence of independent contracting during the period studied—2014 to 2016—there was significant growth in contracting in the transportation sector due to the emergence of rideshare platforms. Platform workers were also most likely to have low incomes and to be young and single than were independent contractors as a whole and were much less likely to be aged 65 or above.

While most workers with platform earnings—79.3 percent—combined wage and salary earnings with income from platform work, the remaining fifth of the platform workforce whose only earnings came from independent contracting accounted for over half—53.2 percent—of all platform earnings in 2016. The researchers note that their findings are consistent with others and that, “most of the driving hours on transportation platforms are done by a small percentage of drivers who do this work for their sole or main source of income.” Platform workers who depended entirely on independent contracting earnings were also far more likely to be concentrated in the bottom ten percent of the earnings distribution. Two-thirds—65.7 percent—of the platform workers in the bottom decile only worked as an independent contractor.

How Do They Pay TaxesHow Do Independent Contractors Pay Their Taxes?

Key Takeaways

Tax filing is more complex for independent contractors because they must track and file forms detailing their income and expenses and are required to pay quarterly estimated tax payments.

One survey found that as many as two-thirds of platform workers received no information reports – Form 1099-MISC, 1099-NEC, or 1099-K – documenting their earnings for tax purposes.

Independent contractors risk missing out on important tax credits and other benefits, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Child Tax Credit (CTC), and are at risk for reduced Social Security benefits upon retirement.

Independent contractors face a number of challenges when it comes time to pay their personal income taxes. Tax filing is generally more complex—since contractors are responsible for quarterly estimated tax payments, for paying self-employment taxes, and for tracking the expenses they incur in generating the earnings they receive—but also because they often have little or no formal information reporting available to help them track the income they earn. The section below reviews the information reporting requirements that apply to various categories of self-employed workers, the tax forms they may be required to file, and their eligibility for tax filing assistance programs.

Tax Reporting Requirements

Federal and state income taxes are based on a system of voluntary reporting backed up by so-called information returns, forms that report amounts paid to individuals and to the IRS. The tax system uses these reports as a tool to boost compliance and accuracy, while tax filers use these reports to document and report their earnings. Wage and salary workers, for example, receive a W-2 from their employer documenting amounts earned, while many independent contractors receive no documentation of earnings at all.

Whether and how independent contractors’ earnings are reported, both to the contractor and to the IRS, depends on factors such as whether the contractor provides goods or services to a business or to an individual and how the payments for those goods and services are made (Figure 5). Importantly, information reporting does not affect the amount of tax that is owed; it is simply a tool that helps ensure that tax filers and the IRS can track the amounts they receive and pay the amount that they legally owe. For example, a business that pays an independent contractor is generally required to send to both the IRS and the contractor an information return—a form 1099—showing the amounts paid to the contractor during the year. The contractor uses the 1099 to report income on their tax return and the IRS can use it to verify that the income is reported. Broadly speaking, independent contractors and the reporting requirements that pertain to their earnings fall into three categories:

- Traditional 1099 workers: Workers who are not employees who provide services to businesses. Examples of this type of contractor include graphic designers or bookkeepers who work on a contract basis. Businesses making payments for services of least $600 to non-employees in the course of their trade or business must report the total amount paid to a contractor over the course of the year to the IRS on a form 1099-NEC and must provide a copy of the 1099 to the contractor. Form 1099-NEC includes boxes to report payments for up to two states, but does not require state-specific information to be reported to the IRS (states may require reporting).

- Workers receiving payments through digital marketplaces: Workers whose earnings come from on-demand labor platforms. These platforms—known as third party settlement organizations (TPSOs)—act as intermediaries between the buyers and sellers of goods and services and are required to report payments made during the year that reach specified thresholds. TPSOs include payment processors, such as Etsy, Venmo, and PayPal as well as gig economy platforms such as Uber, DoorDash, and TaskRabbit. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) lowered the threshold at which TPSOs are required to file information reports, known as 1099-Ks, to payments totaling $600 or more in a calendar year. Prior to ARPA, TPSOs were only required to file reports if payments to a payee in a given year exceeded $20,000 made through more than 200 transactions. This change was intended to improve voluntary tax compliance by providing more independent contractors with information returns (1099-K). However, the IRS delayed implementation of this change which is now scheduled to take full effect in 2026. TPSOs typically report payments on a Form 1099-K.

- Non-1099 independent contractors: This category includes workers who provide services directly to consumers. Examples of non-1099 independent contractors include hair stylists or physical therapists who are paid directly by consumers. Payers do not report payments to these contractors or to the IRS, and contractors must maintain their own documentation and records.

Historically, because of the high threshold for third-party platform reporting described above, many platform workers are not subject to information reporting requirements, with some surveys finding that as few as a third received a Form 1099-MISC or 1099-K in the period studied. As detailed below, the lack of third-party reporting on the earnings of many platform workers contributes to a high level of income underreporting and may, in turn, result in workers not claiming tax credits they would otherwise be entitled to and potentially lower Social Security benefits upon retirement.

Tax Filing Requirements for Independent Contractors

Individuals earning $400 or more from self-employment are required to file a federal income tax return regardless of whether they receive a 1099-NEC, a 1099-K, or no information report at all if, for example, their earnings come from services that fall below the reporting threshold. Independent contractors must report the amounts that they receive in income and can also claim legitimate expenses incurred in producing that income as a business deduction. A rideshare driver, for example, can generally deduct what they spend on fuel, maintenance, car washes, and other expenses incurred in operating their vehicle. The self-employed are also generally required to pay self-employment tax, similar to Medicare and Social Security taxes, on their net earnings (“profits”) from self-employment. Self-employment income is considered “earned income” for calculating eligibility for the Earned income Tax Credit (EITC) and may affect eligibility for, and the size of, Child Tax Credits (CTC).

Figure 6: How Do California’s Platform Workers Compare to Independent Contractors as a Whole?

| California Platform 1099 Workers | All California Workers Engaged in Independent Contracting | ||

| Age | |||

| 18-25 | 20.7% | 9.0% | |

| 26-40 | 45.8% | 32.1% | |

| 41-55 | 24.6% | 33.1% | |

| 56-64 | 6.8% | 15.9% | |

| 65-80 | 2.2% | 9.9% | |

| Filing Status | |||

| Single | 62.6% | 46.6% | |

| Married | 37.4% | 53.3% | |

| Annual Earnings (2016 Dollars) | |||

| $0—$6,416 | 17.1% | 22.1% | |

| $6,417—$12,897 | 13.5% | 14.6% | |

| $12,898—$19,458 | 13.6% | 12.5% | |

| $19,459—$26,470 | 12.4% | 8.8% | |

| $26,471—$34,663 | 12.1% | 7.6% | |

| $34,664—$44,648 | 10.8% | 7.0% | |

| $44,649—$57,874 | 8.8% | 6.6% | |

| $57,875—$77,460 | 6.2% | 6.5% | |

| $77,461—$114,072 | 3.7% | 6.6% | |

| $114,073 + | 1.7% | 7.7% |

Source: Annette Bernhardt, et al, “Independent Contracting in California: An Analysis of Trends and Characteristics Using Tax Data” (March 2022) downloaded from https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Independent-Contracting-in-CA.pdf.

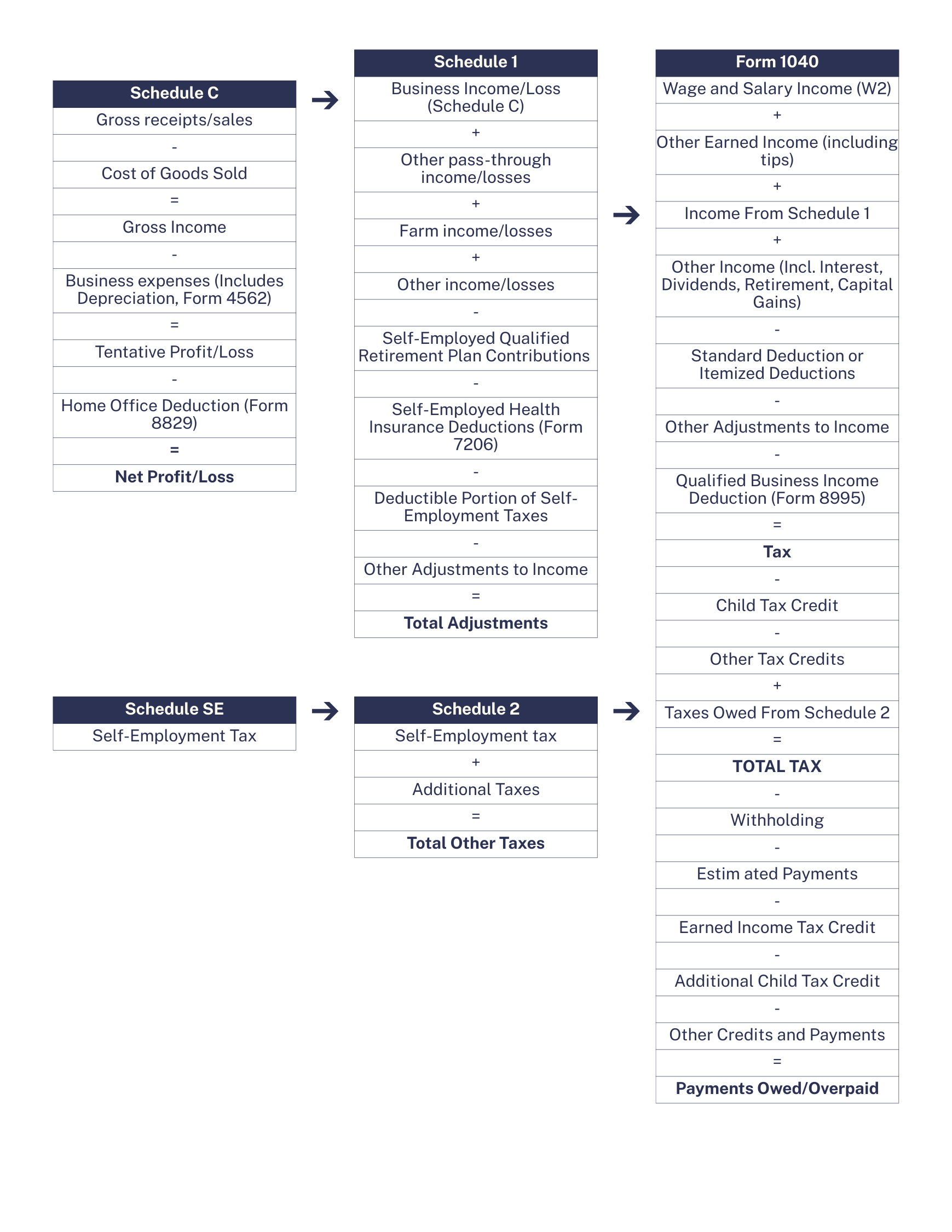

In addition to the basic individual tax return—Form 1040—independent contractors are required to file a Schedule C detailing their business income and deductions and a Schedule SE to account for self-employment taxes owed. Independent contractors engaged in multiple unrelated business activities—such as a graphic designer who also works as a rideshare driver—must file a separate Schedule C for each distinct line of business.

Independent contractors who work out of a home office, who claim depreciation deductions on a vehicle or other equipment, or who purchase health insurance must also complete special tax forms (Figure 6). The self-employed are also eligible to deduct a portion of their income—the so-called pass through or Section 199A deduction—a tax cut that was part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The broad range of information required for independent contractors to file a return makes tax filing complex, exposes contractors to potential penalties, and reduces the amount of taxes owed that are actually paid.

Figure 8: Forms and Schedules Required to Report Self-Employment Income on a Federal Tax Return

Independent Contractors and the Tax Gap

Underreporting of net income by sole proprietors, including independent contractors, is a major contributor to the tax gap, the gap between the amount of taxes legally owed and the amount of taxes actually paid on a timely basis. Underreporting can result from either failure to report the full amount of income earned or overstating expenses. Researchers find that current rules, which require no reporting of earnings for many independent contractors, “virtually ensure” that tax filers will be more likely to misreport their income, eroding revenue collections, and leaving them subject to audit exposure and penalties. Un- or underreported income earned by independent contractors and other self-employed individuals falls into two broad categories: information subject to at least some information reporting requirements and income subject to no information reporting requirements. A study published in 2019 found that 43 percent of platform workers receiving a 1099 failed to file a Schedule C or Schedule SE reporting self-employment income. While most of these individuals did file a tax return, it is not clear whether these individuals reported any or all their self-employment income on their 1040. And some 1099 recipients—8.6 percent in 2016—failed to file a return at all. These findings are echoed in a 2018 survey by an accounting software vendor that found that 32 percent of self-employed workers admitted to underreporting their income while 36 percent admitted to not filing taxes at all.

Taken together, taxes on business income owed, but underreported, for personal income tax purposes and underreported self-employment taxes accounted for 28 percent and 10 percent of the 2022 tax gap respectively according to the IRS’s most recent tax gap report. By contrast, the same report estimated that wages, salaries, and tips that are subject to information reporting and withholding accounted for just 1 percent of the tax gap, despite making up a much larger share of total compensation. Overall, the IRS estimated that just 1 percent of income subject to “substantial” reporting requirements along with withholding was misreported in tax years 2014-16, while 55 percent of income with little or no reporting was misreported and 6 percent of that with “substantial” information reporting but no withholding was misreported for tax purposes.

The Congressional Research Service has identified misclassification of independent contractors as a significant contributor to underreporting. Misclassification occurs when employers treat workers as independent contractors who should more properly be considered employees. Because employers are required to withhold income taxes, withhold and pay Social Security and Medicare taxes, and pay any payroll taxes due on wages paid to employees, but not on payments to independent contractors, nearly all wages are accurately reported to the IRS as noted above. Past research has estimated that 15 percent of employers and potentially more engage in misclassification. In addition to widening the tax gap, misclassification imposes substantial costs on workers in the form of lost wages, benefits, and contributions to unemployment, workers compensation, Social Security, and Medicare. The Economic Policy Institute, for example, estimated that illegal misclassification costs the typical construction worker between $10,177 and $16,729 a year.

Un- or underreported income not only undermines federal and state revenue collections, it can also translate into lower Social Security benefits upon retirement for workers who fail to pay self-employment taxes. A worker’s initial Social Security benefits are based on their 35 highest years of earnings and age at retirement. Thus, workers with fewer than 35 years of fully reported earnings would receive less upon retirement than if they had paid the self-employment taxes due. Similarly, filers that understate or fail to report their income may miss out on valuable income supports—the EITC and CTC —that can not only reduce taxes owed, but also put money back in workers’ pockets.

Available ResourcesWhat Resources Are Currently Available to Assist Tax Filers?

Key Takeaways

The IRS estimates that preparing a tax return takes personal income tax filers with business income, including as independent contractors, an average of 24 hours and costs an average of $620.

Lack of information about tax filing obligations is common among platform workers. One survey found, for example, that one-third were unaware that they were required to pay self-employment taxes and make quarterly estimated tax payments and close to half didn’t know that they were entitled to deductions for business expenses, such as gas costs incurred by a rideshare driver.

Most no-cost tax assistance programs limit the scope of assistance they provide to independent contractors and, overall, these programs are underutilized relative to the number of eligible tax filers.

For many low- to middle-income workers, tax filing can be complex, and it can be costly. The IRS estimates that, on average, personal income non-business tax filers spend about 8 hours and $160 preparing and filing their tax returns. However, for business filers—such as independent contractors—the cost rises to $620 and 24 hours. And while lower-income workers with relatively simple tax returns have access to assistance, those with more complex returns have more limited options. Lack of access to assistance can exacerbate non- or underreporting. One survey of platform workers, for example, found that about one-third were unaware that they were required to pay self-employment taxes and make quarterly estimated tax payments; 36 percent did not understand what type of records were needed for tax purposes; and 43 percent were unaware of how much they would owe in taxes and did not set money aside to pay any taxes due. Similarly, the survey found that almost half—47 percent—didn’t know that they were entitled to deductions for business expenses, such as gas costs incurred by a rideshare driver.

Three Hypothetical Independent Contractors

Jose, aged 31, is a rideshare driver. He’s married to Maria, and they have two children, Isabella, age 8, and Tony, age 6. Jose was paid $32,000 for driving last year, which is reported on a 1099-K by the rideshare app. Maria earned $24,000 as an employee in a childcare center. The children receive health coverage through Medi-Cal and Jose and Maria have health purchased coverage through Covered California. Jose drove 15,000 miles for work last year and used the same vehicle for personal use for 10,000 miles. He owns the car and makes monthly car payments.

Jose and Maria file a joint tax return and report Jose’s rideshare earnings on a Schedule C. Jose claims a deduction for the miles he drives for work using the standard mileage rate of $0.67/mile in 2024 in lieu of tracking and reporting what he spends on gas, repairs and maintenance, depreciation, license fees, insurance, vehicle license taxes, roadside assistance, and car washes. He separately tracks and deducts what he spends on parking, bridge tolls, his cell phone and cell phone service, commissions charged by his rideshare company, and miscellaneous expenses such as hand sanitizer, tissue, and a phone charger. He also deducts the cost of the app he uses to track his expenses. Jose and Maria are eligible for assistance through VITA but have typically gone to a tax preparer who works in their neighborhood to file their tax return.

Jose and Maria’s health coverage is a bronze plan, and the Premium Tax Credit covers all of their monthly premium costs but leaves them with high out-of-pocket costs if they have to go to a doctor. He pays self-employment tax and he and Maria claim the CTC and EITC.

Because Jose uses the standard mileage rate for calculating his vehicle-related expenses, his tax return is fairly simple. Drivers that opt to deduct actual vehicle expenses would have more complex returns largely due to the special rules that apply to depreciation.

Nathalie, aged 45, is a freelance graphic designer who works from home. She has an established client base of small businesses that generated $65,000 in gross income last year. She’s single and owns a condo with a small home office that she uses as her studio. All of her income is reported on 1099-NECs by her clients.

Nathalie deducts her costs of doing business: a high-end computer, monthly software subscription costs, her business cell phone, the annual fees for her website, office supplies, the cost of ads that she places in several small business association newsletters, and travel costs to her clients’ offices. She also deducts annual membership dues for several professional associations that she joined for networking purposes and the cost of occasional workshops she attends to upgrade her skills. She can also deduct the cost of her business credit card and interest charges she incurs if she has to carry a balance when a client is late on payment. She buys, and can deduct, the cost of health insurance bought through Covered California, while she receives some assistance from the Premium Tax Credit, she still pays $2,600 per year towards her premiums. She contributes $1,500/year to a SEP-IRA for her retirement, also a deductible cost. She pays self-employment taxes.

Nathalie uses the simplified method for deducting costs related to her home studio. The simplified method gives her a deduction of $5/square foot up to a maximum of 300 square feet. Since her studio is 100 square feet, she is well below the maximum. She could probably save more if she deducted actual costs, but she finds the complexity to be daunting and is concerned about the implications of claiming depreciation deductions if she decides to sell her condo someday. Nathalie would be eligible for assistance through VITA or for no-cost software through Free File but has typically used software that she pays for to prepare her own return.

Anna, aged 40, works as a hair stylist and rents a stall at a small salon in her neighborhood. She’s single and has one child, an 8-year-old daughter named Charlotte. She earns $45,000 a year. She pays $50 per month to send her daughter to a subsidized afterschool program at a local community center.

Anna can deduct her monthly stall rental payments, the cost of her equipment—she provides her own hairdryer and cutting shears; supplies such as shampoo and conditioner; her annual license fee; and the cost of ads she places in a local parents’ newsletter. Charlotte is eligible for Medi-Cal because the family’s income is below 266 percent of the federal poverty line. Anna has a Bronze plan through Covered California which has high out-of-pocket costs, but no monthly premium due to the Premium Tax Credit. She is worried about what might happen if Congress doesn’t extend aid for people like her. Anna wants to make sure that Charlotte can go to college some day and has always contributed $50 per month to a 529 college savings plan, even though the family’s budget is tight.

In addition to the aid she receives from the Premium Tax Credit, Anna claims the EITC, CTC, and Child and Dependent Care Tax Credits and pays self-employment taxes.

Because her clients pay her directly in cash or through payment apps such as Venmo and Zelle only some of her income is reported on a 1099. In the past, almost none of her income was subject to information reporting because she uses multiple apps and she never reached the tax reporting threshold. Anna uses free accounting software she found online to track her income and expenses. While she tries to be as accurate as possible when filing her taxes, she worries about getting audited ever since her sister-in-law told her that claiming the EITC would make her “audit bait.” Last year, Anna received help preparing her tax return through a VITA site located at the community center where Charlotte goes after school.

In 2024, the IRS took an important step towards making tax filing easier and less costly, launching Direct File, a free, online tool that allows tax filers to prepare and submit their tax returns directly with the IRS. In its first year of operation, Direct File was available in 12 states, including four states—one of which was California—that agreed to link a no-cost state filing tool to the IRS’s Direct File and eight states with no state income tax. Access to Direct File was expanded to 25 states and 32 million eligible taxpayers in 2025. In 2025, Direct File covered more types of income, more credits, and more deductions than in 2024.

Prior to the introduction of Direct File, filers seeking no-cost assistance with their taxes could seek assistance from the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) and Tax Counselling for the Elderly programs, administered by community-based agencies and local governments; the Department of Defense operated MilTax program for active duty military, the families, and others with a close connection to military service; or the Free File program, a portal offering access to a variety of tools offered by private software companies (Figure 7). The range of tax situations covered differs among the four programs, as do the populations served. Currently, the VITA and Free File programs offer limited support to individuals with self-employment income while MilTax covers a broader range of situations. Individuals with self-employment income are not currently able to use Direct File.

Figure 7: Information Reporting Requirements

| Payor | Payment Threshold | Payments Covered | Comments | ||

| 1099-K | Payment apps; payment card companies, including credit and debit card card companies; and online marketplaces. Includes payors such as craft or “maker” marketplaces, ride-hailing platforms, freelance marketplaces, ticket resale sites, auction sites, and short-term rental platforms | Payments for goods and/or services that total over $5,000 in 2024, more than $2,500 in 2025, and more than $600 in 2026 and thereafter | Goods sold, services provided, or property rented. | Payors can file a 1099-K for amounts paid below the $5,000 threshold. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 reduced the 1099-K reporting threshold from payments exceeding $20,000 made through at least 200 transactions. | |

| 1099-NEC | Individuals or businesses, including nonprofit organizations and governments. | Payments of $600 or more over the course of the year | Payments for services provided in the course of business to someone who is not an employee. | Reporting is not required if the payment is made to a corporation or LLC under most circumstances. | |

| 1099-MISC | Individuals or businesses, including nonprofit organizations and governments. | Payments of $600 or more over the course of the year | Payments made during the course of business to attorneys and specified other payments. |

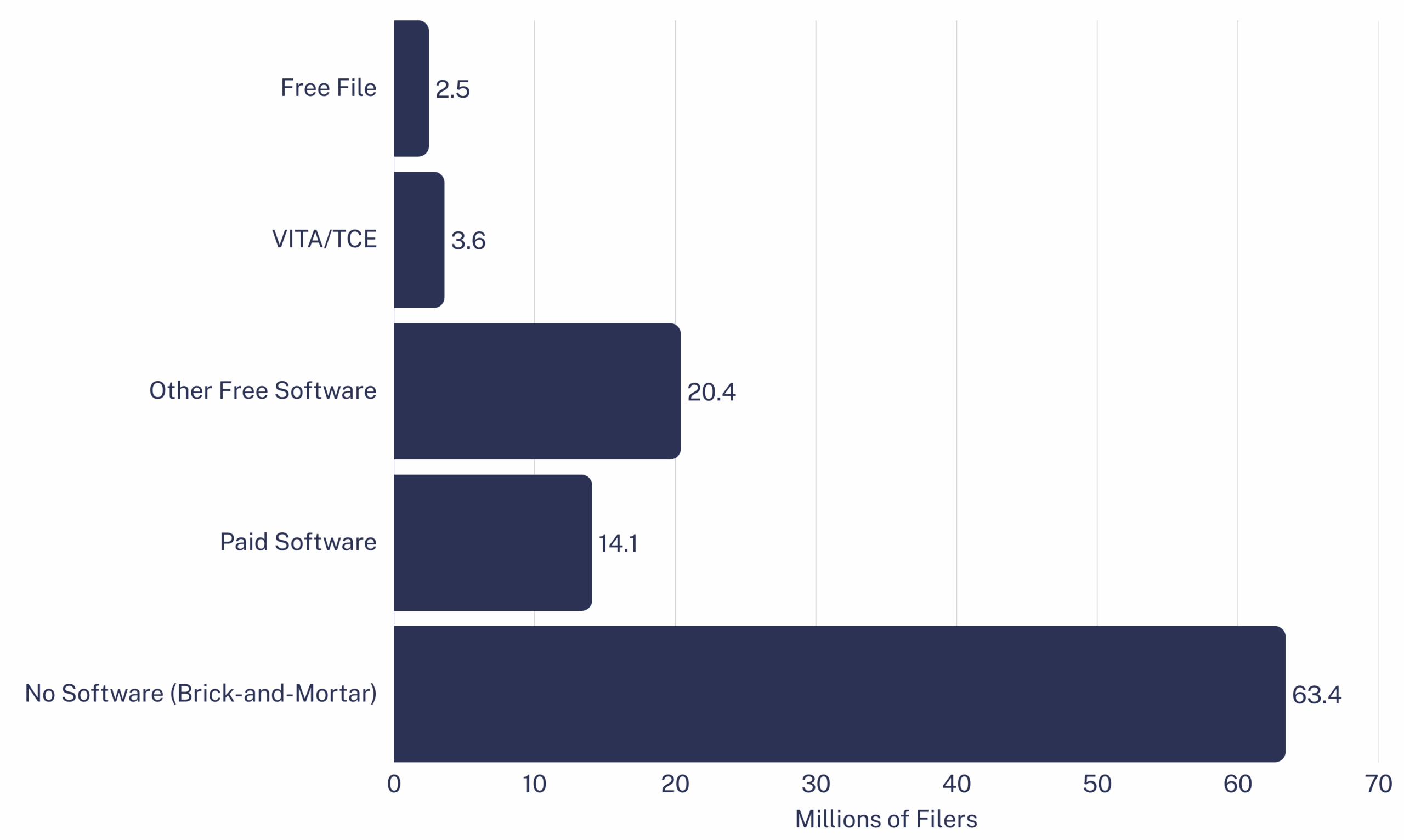

While a large share of American households are eligible for assistance through the VITA program, only 3.6 million of 150 million households filing tax returns in 2019 used the program. This surpassed the 2.5 million households who used Free File, which provides access to free software provided by private software companies. The vast majority of low- and middle-income households paid for software that they should have received for free or paid to have their returns prepared by private tax preparers. By contrast, 140,803 tax filers submitted accepted returns as part of the IRS’s 2024 Direct File pilot program, which provided an option to file a tax return directly with the IRS for free. Filing assistance efforts—such as Direct File and VITA—can also help ensure that tax filers claim credits, such as the EITC and CTC, for which they are eligible. Making it easier and less costly to file a return can help boost participation in these credits while helping to ensure that filers fulfil their obligations.

Figure 9: No Cost Tax Filing Resources: 2025 Filing Season

| Direct File | Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA)/Tax Counseling for the Elderly (TCE) | Free File | MilTax | ||

| Geographic Availability | AK, AZ, CA, CT, FL, ID, IL, KS, ME, MD, MA, NV, NH, NJ, NM, NY, NC, OR, PA, SD, TN, TX, WA, WI, WY | Varies by locality. | National | National | |

| Services Provided | Web-based guided tax preparation tool with access to IRS customer service and links to state filing portals. | Free basic tax return preparation assistance by trained volunteers. Some sites offer a “self-prep” option with access to volunteer support. | Access to guided tax preparation software. Forms supported vary by vendor. Items listed below are supported by all vendors. Some, but not all, vendors provide access to state return filing. | Specialized software and access to professional tax specialists. Covers federal and up to three state returns. | |

| Language Support | English and Spanish | Varies by location | English and Spanish | Document and real-time language translation services available in more than 150 languages | |

| Limitations on eligibility | Limitations apply for households with wages > $125,000. Direct File is not available if filer’s wages are > $200,000 ($168,600 if multiple employers); for married filing jointly households and combined wages are > $200,000 ($168,600 if spouse had multiple employers); for married filing jointly households with combined wages > $250,000; or for married filing separate filers with wages > $125,000. | Generally limited to people with incomes of $67,000 or less. TCE focuses on persons aged 60 or older and specializes in questions on retirement related issues. | Income limitations vary by vendor. Eligibility is limited to adjusted gross incomes of $84,000 however, some vendors impose a lower cap. | Full services only available to active duty military members, immediate family, survivors, recent veterans, military academy cadets, foreign military service members, and certain other individuals. Limited services available to some other populations. See: https://www.militaryonesource.mil/military-basics/millife-essentials/eligibility-for-confidential-support-services/. | |

| Will not prepare Schedule C with loss, depreciation, or home office deductions; complicated Schedule D, requests for Social Security Numbers or Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers; returns with casualty/disaster losses; non-deductible IRAs, Form SS-8 for determination of worker status for purposes of federal employment taxes and withholding, Form 8814 for children taxed at parent’s tax rate. | Limitations apply to the use of certain schedules (see: https://www.irs.gov/e-file-providers/free-file-fillable-forms-program-limitations-and-available-forms#form-1040-sr). Certain forms are not available for e-filing. | ||||

| Serves returns with income from | Wage and salary income (Form W-2), unemployment insurance (Form 1099-G), social security benefits (SSA-1099), interest income (Form 1099-INT), and Alaska Permanent Fund Dividends. Distributions from employer-sponsored retirement plans such as 401(k), pension, annuity, 403(b), or 457(b) plans (1099-R). | Wage and salary income (Form W-2), self-employment income (limited, Form 1099-MISC, Form 1099-NEC, and Form 1099-K), gambling winnings (Form W-2G), cancelation of debt (limited, Form 1099-C), unemployment insurance (Form 1099-G), social security benefits (Forms SSA-1099 and RRB-1099), health savings account distributions (limited, Form 1099-SA), interest income (Form 1099-INT), dividends received (Form 1099-DIV), simple capital gains/losses (Form 1099-B), home sales (limited, Form 1099-S), limited cancelation of debt (Form 1099-C), state tax refunds (Form 1099-G), IRA and other retirement distributions (Forms 1099-R, RRB-1099-R, CSA-1099). | Wage and salary income (Form W-2), self-employment income (Form 1099-MISC, Form 1099-NEC, and Form 1099-K), profit or loss from business (Schedule C), profit of loss from farming (Schedule F), gambling winnings (Form W-2G), limited cancellation of debt (1099-C), unemployment insurance (Form 1099-G), social security benefits (SSA-1099 and RRB-1099), health savings account distributions (Form 1099-SA), interest and dividends (Schedule C), capital gains/losses (Schedule D, Form 1099-B), limited home sales (1099-S), limited cancellation of debt (Form 1099-C), state tax refunds (For 1099-G), IRA and other retirement distributions (Form 1099-R, RRB-1099-R, CSA-1099). | Schedule C and wage and salary income. | |

| Some Free File entries must be done manually: https://www.irs.gov/e-file-providers/free-file-fillable-forms-program-limitations-and-available-forms | |||||

| Deductions | Standard deduction, student loan interest, and educator expenses | Limited itemized deductions | Itemized deductions with limitations, employee business expenses (Form 2106) | ||

| Savings and retirement | Includes contributions and distributions from Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) or Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) | Limited Health Savings Accounts | |||

| Includes contributions and most distributions to employer-sponsored retirement plans, such as 401(k), 403(b) or 457(b) accounts | |||||

| Includes rollovers from one employer-sponsored retirement plan to another | |||||

| Does not support contributions to an IRS, except rollover contributions, or distributions from an IRA. | |||||

| Tax Credits | Child Tax Credit, Credit for Other Dependents, Child and Dependent Care Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit, Premium Tax Credit, Saver’s Credit; and Credit for the Elderly or the Disabled | Education Credits (Form 1098-T), Child Tax Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit | Earned Income Tax Credit, Credit for the Elderly or Disabled, limited Foreign Tax Credit (Form 1116), Child and Dependent Care Expenses (Form 2441), “green” tax credits with some limitations; saver’s credit, premium tax credits, and others (some with limitations) | ||

| Other features | Ability to import W-2 and other information directly from the IRS | Will prepare prior year and amended returns. | Only basic calculations are supported. Users must perform some calculations themselves. | ||

| Household employment taxes (Schedule H), Self-Employment Tax (Schedule SE) | |||||

| For a full list of forms and limitations, see: https://www.irs.gov/e-file-providers/free-file-fillable-forms-program-limitations-and-available-forms | |||||

| Administered By | Internal Revenue Service | Local public agencies and community-based programs | Private software companies through the Free File Alliance | Department of Defense | |

| For more information | https://www.irs.gov/filing/irs-direct-file-for-free | https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3676bsp.pdf | https://www.irs.gov/filing/irs-free-file-do-your-taxes-for-free | https://www.militaryonesource.mil/benefits/miltax-free-tax-services/ |

Figure 10: Tools Used by Households Eligible for Free File to Pay Their 2019 Taxes

Based on a survey of tax filers who met Free File eligibility criteria, which include an income cap of about $72,000.

Source:

Cassandra Robertson and Samarth Gupta, “Improving Public Programs for Low-Income Tax Filers” (New America Practice Lab, April 18, 2022) downloaded from https://www.newamerica.org/new-practice-lab/reports/improving-public-assistance-for-low-income-tax-filers/.

The Long Road to a Public Tax Filing Option

The 2024 introduction of Direct File was the culmination of a multi-decade, bipartisan effort to create a free public option for filing a tax return directly with the IRS. Intense lobbying by private tax preparation companies blocked prior efforts and, instead, resulted in the creation of the Free File Alliance. Created in 2002, the Free File Alliance required participating software companies to provide free tax-filing software to filers with income below a set limit ($84,000 for the 2024 tax year).

Almost from the beginning, Free File was beset with problems. Over the years, Free File was cited for deceptive advertising by the Federal Trade Commission, and New York State Attorney General Letitia James reached a $141 million settlement with Intuit, the maker of TurboTax, over practices that resulted in tax filers paying for services that should have been free. Reports also accused TurboTax of hiding Free File from web-based search services in order to drive traffic to its paid software product. These problems and others led the U.S. Government Accountability Office and consumer advocates to push for a free electronic filing tool.

RecommendationsRecommendations

A range of actions could make tax filing easier for independent contractors, help ensure they receive the tax credits they have earned, and boost compliance with the tax code. While ultimately the IRS should strive to create a comprehensive online filing tool, there are a number of steps that can make tax filing easier and cheaper for independent contractors in the meantime. Appendix A details areas of greater complexity that may take longer to implement and/or require additional feasibility analysis. Actions that the federal government could take immediately include:

- Expanding the scope of the IRS’s Direct File program to include relatively simple independent contractor returns. As part of a pathway to a comprehensive online filing platform, the IRS should incorporate the basic functionality needed for independent contractors to file simple tax returns. As a first step, that could include the ability to complete a Schedule C for individuals with relatively simple tax situations such as those with no employees; those who either do not claim vehicle expenses or who use the standard mileage rate; and those who either do not claim, or who use the simplified method for claiming, a home office deduction (See Appendix A).

- Expanding and aligning information reporting requirements. The IRS should move quickly to implement expanded 1099 reporting requirements mandated by ARPA described above. Reporting requirements should be extended to other payment processing systems—such as Zelle and Apple Pay—that process payments for services. Congress should also act to align 1099-MISC and 1099-K reporting requirements to minimize confusion for payers and workers, alike.

- Implementing mandatory withholding. Many independent contractors face unexpected tax bills when it comes time to file their tax returns due to the lack of ongoing withholding. Coupled with strengthened reporting requirements, imposing at least a minimum level of withholding as recommended by the U.S. Government Accountability Office and the IRS’s Taxpayer Advocate Office could help avert this problem.

- Improving data sharing between federal and state tax authorities. Requiring the IRS to improve and expedite sharing information reported on 1099s would make it easier for state tax agencies to establish online filing portals and could be used to pre-populate tax returns filed through such portals.

- Requiring the IRS to develop and publish guidance for online platforms to use as part of onboarding workers and sellers. The IRS could expand upon resources provided by its existing gig economy tax center to cover a greater range of work arrangements.

- Requiring the IRS to develop tools to help tax filers track the information needed to file their tax returns. The IRS could be required to develop online tools that independent contractors could use to track the information needed to accurately file a tax return. Tools such as a mileage and expense tracker for rideshare drivers or an estimated tax payment calculator could be integrated into Direct File, making tax filing easier for workers while minimizing opportunities for errors.

Actions that California could take include:

- Conforming to federal adoption of any of the recommendations listed above. California could make conforming changes to the state’s CalFile platform and state tax laws so that any tax filer eligible to use Direct File is able to use CalFile to file a California tax return.

Actions that the federal, state, or local governments could take or that philanthropy could support include providing dedicated resources to VITA programs, worker centers, unions, and other community-based organizations to provide tax filing assistance to platform workers and other independent contractors. Organizations that focus on specific segments of the contractor workforce—such as rideshare drivers’ organizations—or that serve workers with a primary language other than English—may be particularly well-situated to provide specialized filing assistance.

Areas for Future Research

Additional research would shed light on how best to meet independent contractors’ needs for assistance in filing their tax returns. Most notably, the expansion of Direct File to more tax filers in more states will provide important information on how best to incorporate more complex filing situations. Other areas where additional research would be useful include:

- Updating the UC Berkeley Labor Center research for changes in the economy. While the overall demographic profile of the independent contractor workforce presented by the Berkeley researchers is consistent with more recent data, updating that research, which is based on tax data from 2014 to 2016, would provide the data needed to ensure that programmatic changes reflect the current state of the workforce.

- Replicating the UC Berkeley Labor Center research in other states and/or for the nation as a whole.

- Qualitative research, such as focus groups with key segments of the independent contractor workforce, could help shed light on the specific challenges workers face when filing a tax return and how best to address them.

- Research into the specific filing challenges faced by complex families, including those with mixed immigration status, could help ensure that tools such as Direct File minimize inadvertent errors while ensuring that families receive the tax credits that they are entitled to. This research should include how best to ensure confidentiality of tax filer identifying information as well as the confidentiality of requests for information and assistance.

Conclusion

Independent contractors account for a sizable and diverse share of the workforce and confront distinct challenges when filing their tax returns. The rise of platform-based work has brought new attention to the challenges faced by independent contractors, creating an opportunity to spotlight long-standing issues and open the door to targeted solutions. Simple reforms such as expanding the range of payments subject to information reporting requirements and extending the scope of filing situations eligible to use Direct File and qualify for tax assistance programs such as VITA can reduce complexity for filers, help ensure they claim important benefits, and can improve tax compliance.

The author wishes to thank Miles Johnson, Teri Olle, Allen Prohofsky, Kelli Smith, and Gabriel Zucker for their helpful comments during the preparation of this report.