Tax Fight 2025

The Equity & Prosperity Agenda: A Tax Plan to Promote a Fair, Inclusive, and Competitive Economy

10. 30. 2024

Congress can lower costs for working families, promote competitive tax policies, and invest in a stable, thriving economy for all.

The expiration of the Trump Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2025 is a critical opportunity to set economic policy for the next decade. The TCJA has been an abject failure for American families. Every year since it passed in 2017, it has diverted taxpayer money to exorbitant tax breaks for the ultrawealthy and powerful corporations while everyday Americans have struggled to make ends meet. The 2025 tax fight is our opportunity to promote competition and curb corporate concentration, lower costs for working families, raise the revenue we need to invest in core priorities and promote a democratized, multiracial economy.

The Affordability CrisisAmerican Families are Facing an Affordability Crisis While Corporate Profits Soar

For most Americans, the rising cost of living has made it increasingly difficult to get by, let alone get ahead. Even with inflation slowing and a stable job market, corporations have used their market power to keep the prices of everyday necessities like groceries, gas, and rent high and rising. And while wages have grown with inflation, especially low-wage sectors, they have not grown across every sector. Credit card debt has increased by 39% since the COVID pandemic began—and delinquency rates have risen sharply over the last two years. Too many families simply can’t balance the budget each month.

For ultrawealthy families and powerful corporations, the story is the opposite. In the decade before the COVID recession, corporate profits skyrocketed while labor income declined: over that period, $600 billion a year was transferred from workers to corporate profits. Since the start of the COVID pandemic, billionaires in the U.S. have virtually doubled their combined wealth, largely off the backs of American workers and consumers. While some of the biggest American businesses grew $1.5 trillion richer coming out of the pandemic recession, their workers saw less than 2% of that benefit. Our economy has grown more concentrated, and corporations continue to charge consumers more even as their input costs have come down.

A Modern Tax CodeA Modern Tax Code Must Promote an Inclusive Economy That Works for Consumers, Workers, and Small Businesses

The tax code is more than just a way to raise revenue to fund shared investments. Tax policies can – and should – be designed to incentivize productive business investment and fair competition. They can also reward businesses for being better stewards of their resources and champions of a robust, multiracial democracy; require corporations to treat their employees and consumers more humanely; and shape the marketplace to encourage innovation and entrepreneurship and serve communities, especially communities of color, rather than the reverse. Right now, our tax code does the opposite: it rewards corporate concentration and wealth hoarding to the detriment of small businesses and American communities.

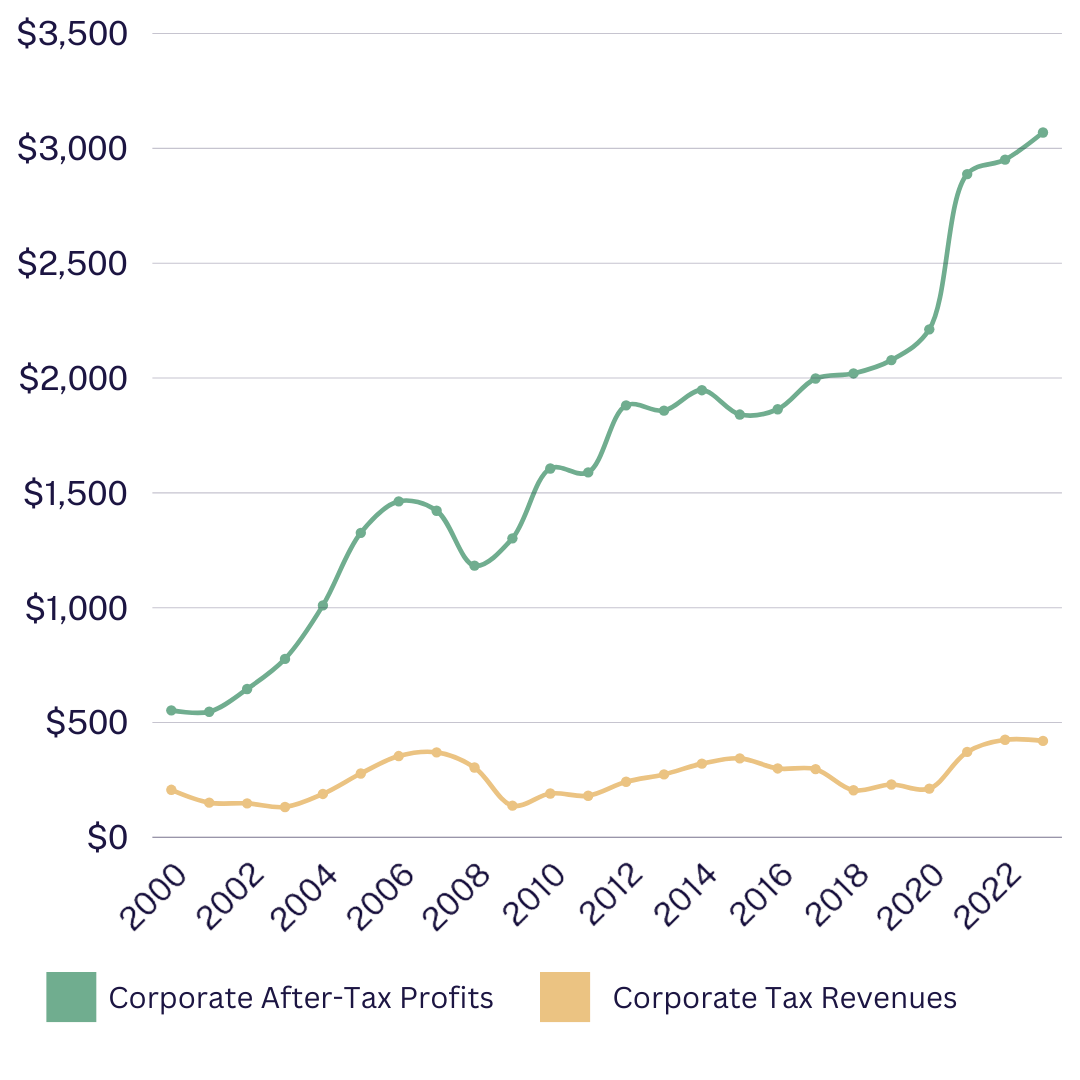

Corporations benefit immensely from the shared investments that our taxes pay for, from our infrastructure and an educated and healthy workforce to a tax and regulatory regime that increasingly promotes—instead of curbs—unhealthy concentration. Still, corporations do not pay their fair share, and anticompetitive tax preferences have driven corporate income tax revenue to historically low levels. In 2025, we can enact a tax regime that encourages a fair, inclusive, and competitive economy that prioritizes people over corporations.

Corporate Tax RatesMake Corporations Pay Their Fair Share Toward Real Prosperity

Raise the corporate alternative minimum tax. In the last few years, corporations have been more profitable than they have ever been, reaching $2.8 trillion in profits in the last quarter of 2023. Research from the Roosevelt Institute reveals that the U.S. tax structure increases the share of the largest American corporations’ profits by 3.79 percentage points. Yet, the TCJA repealed the corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT) and lowered the corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%, the lowest the top rate has been since 1939. A higher alternative minimum tax would require all corporations to pay a minimum share of the profits they report to their shareholders, regardless of the tax breaks they employ.

Corporate tax revenues stagnate as profits skyrocket

Corporate after-tax profits and corporate income tax revenues, billions of dollars, 2000-2023

Impose a graduated corporate tax rate. Even though the corporate tax rate is a flat 21%, the effective tax rate of the biggest 10% of corporations is consistently 11 to 16 points lower than the other 90% of corporations. That’s because huge businesses employ teams of lawyers to avoid paying corporate taxes. 55 of the largest corporations— including Charter Communications (owner of Time Warner Cable, Spectrum Networks, and Comcast, among others), Dish Network, and American Electric Power (which operates electric power companies in 11 states) and recognizable brands like Nike, FedEx, and Salesforce.com—paid $0 in corporate taxes on 2020 profits. They do this by employing tax evasion tactics like shifting their profits to tax shelters, taking advantage of tax breaks for research and experimentation, or writing off capital investments. The largest businesses’ ability to skirt taxes while smaller businesses are required to pay increases the already significant advantages the biggest businesses have. Paying less in taxes means the largest corporations can keep more resources to scale and expand their businesses, further cementing their market power and making it impossible for small and medium-sized businesses to compete.

To avoid increasing this imbalance, Congress should reinstate a progressive, graduated corporate tax where multibillion-dollar corporations pay a higher rate than small businesses and new market entrants. For example, Congress could set several graduated rates between 21% for profits of less than $100 million in profits, up to 35% for profits above $10 billion. This would leave corporate taxes unchanged for the vast majority of corporations and only increase taxes on the very small number of megacorporations that bring in the greatest profits but could generate about $90 billion per year, about a 35% increase above baseline corporate tax revenue.

Stop rewarding anticompetitive corporate mergers with tax breaks. Dominant corporations benefit from already concentrated markets that allow them to dictate prices and suppress wages, costing the average household $5,000 a year. This is further exacerbated by huge mergers that have become commonplace in the American economy. They allow a small number of firms to dominate markets in the name of increased efficiency, but in reality, mergers rarely generate additional benefits for the economy and instead hurt workers and consumers with little to no gain in efficiency.

These harms are especially evident in a few industries: hospital mergers, which increase patients’ costs and fail to improve quality; the pharmaceutical industry, which stifles life-saving research and development and drives up medicine costs; Big Tech, which tamps down on innovation, disadvantages startups, and limits consumer choice; and concentration in the food industry, in which just a handful of companies own 70% of the world’s agriculture market and, if the Kroger-Albertsons merger succeeds, the new mega-corporation and Walmart could control between 70% and 90% of the grocery industry in more than 160 cities.

We need strong federal and state antitrust laws and enforcement to combat harmful mergers, and the tax code is a critical and underutilized complementary tool to stop incentivizing anticompetitive mergers and unhealthy corporate concentration. One step is ending tax-free reorganizations. Current law often allows an acquiring firm and shareholders to avoid (or defer indefinitely) paying taxes on the increase in value of the firm it acquires, as long as the acquiring firm does so by exchanging stock. Unsurprisingly, a significant number of mergers take advantage of this loophole: from 2017-2022, stock was typically involved in about 30% of acquisitions. A recent bipartisan proposal from Sens. Whitehouse and Vance would end this loophole for mergers between firms with a combined income of $500 million during the prior three years.

Close the door to offshore tax havens and enact a global minimum corporate tax. Our tax law allows corporations to pay less in taxes on offshore profits than U.S. profits, so the largest American companies claim an inordinate amount of their profits as earned in foreign tax shelters. As just one example, U.S. corporations claim they earn profits in the Cayman Islands equal to 20 times the GDP of that country. Relying on this and other loopholes, dozens of large companies have gotten away with paying nothing in corporate taxes under the TCJA.

To prevent a race to the bottom and losing billions in tax revenue, offshore profits should be taxed the same as domestic profits. The U.S. and more than 130 countries took steps in 2021 toward this goal by endorsing a 15% global minimum tax. However, since then, Congress has refused to approve the deal, and since the U.S. corporate tax rate is still higher at 21%, American multinationals can skirt domestic corporate taxes by finding low-tax jurisdictions to book their profits. The Biden administration’s restoration of a 15% CAMT was an attempt to stem this corporate tax evasion, but it applies just to the largest corporations —about 80 firms—that book at least $1 billion in income in three consecutive years, and it imposes a lower rate than the regular corporate rate.

This patchwork isn’t working: we need a comprehensive solution that incentivizes companies to keep their business, jobs, and tax revenue here, by requiring them to pay tax on foreign income at least equal to the domestic corporate rate. A global minimum corporate tax of just 21% would bring in more than $160 billion in additional revenue per year—enough to cover the cost of cutting child poverty in half through a fully refundable CTC. International tax experts urge a global minimum tax rate of 25%. A bill recently proposed by Sen. Whitehouse and Rep. Doggett would curb the use of foreign tax havens by eliminating deductions for global intangible low-tax income (GILTI) and foreign-derived intangible income, applying GILTI on a per-country, rather than worldwide, basis, and repealing or restricting several other provisions that allow U.S. companies to disguise themselves or their profits as foreign to evade U.S. corporate taxes.

Raise taxes on stock buybacks to encourage investment in workers and product and service innovation. Because stock repurchases or “buybacks” receive tax preferences, many companies opt to use their profits to purchase outstanding shares of their own company. These buybacks serve two purposes: to inflate the value of the remaining stock on the market, and to compensate shareholders—often top executives in the company—with the added bonus of tax deferral. These gains skew to the rich: the wealthiest 10% of Americans now own 92.5% of the stock market, the highest level ever recorded.

To achieve fairer taxation and encourage investment in workers and companies’ growth instead, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) included a 1% excise tax on all stock buybacks. The Penn-Wharton model suggests that an excise tax of at least 4.6% would be necessary to achieve equal tax treatment between buybacks and dividends to compensate shareholders. But as the Roosevelt Institute points out, stock buybacks are much more valuable for the highest-worth companies. Therefore a graduated excise tax between 1% and 10% based on the size of the buyback would better address the inequity.

Reduce incentives for financialization to reverse the harms that corporate power has caused in communities of color. The increasing financialization of our economy, supported by tax preferences for debt financing, allows Wall Street to play a larger role in how money moves through the economy, while Main Street shrinks. Defined by economist and scholar Lenore Palladino as “the shift within public companies from making money off of selling goods and services to making a higher proportion of their profits off of financial activity—and sending those profits back to shareholders rather than investing them in the firm or its workers,” corporate financialization destabilizes the economy by hoarding money among the wealthy few, instead of letting it flow through local economies via customers, workers, and small businesses. It removes corporate incentives to reinvest in their businesses and workers because their profits rely increasingly on financial maneuvers than the actual production of workers. But perhaps more importantly, concentration in wealth among the white elite—who make up 96% of America’s wealthiest people— disadvantages everyone else, and disproportionately Black, Indigenous, and other people of color.

As Hamilton and Neighly describe in “The Racial Rules of Corporate Power,” the compounding impacts of structural racism, residential segregation, and capital disinvestment in poor communities allow powerful corporations to both abandon and exploit Black and Brown communities. Increasing financialization and excessive market power makes it easier to discriminate against workers and set lower wages, creates the conditions for precarious work situations, and makes communities of color particularly vulnerable to the abuses of corporate greed. In addition to the important policies laid out above, raising taxes on stock buybacks and limiting tax preferences for debt financing would remove some of the incentive for harmful financialization.

End tax subsidies to industries that actively harm society. The tax code is rife with tax breaks that reward industries that directly harm our society as a whole, for example, subsidies for the gas and oil industry, plastics, and unsustainable agriculture practices. Government investment in these profiteering industries makes our environment less healthy, increases inequality, and limits our ability to innovate sustainably. We can reverse these incentives by removing the tax breaks these industries rely on to grow their power.

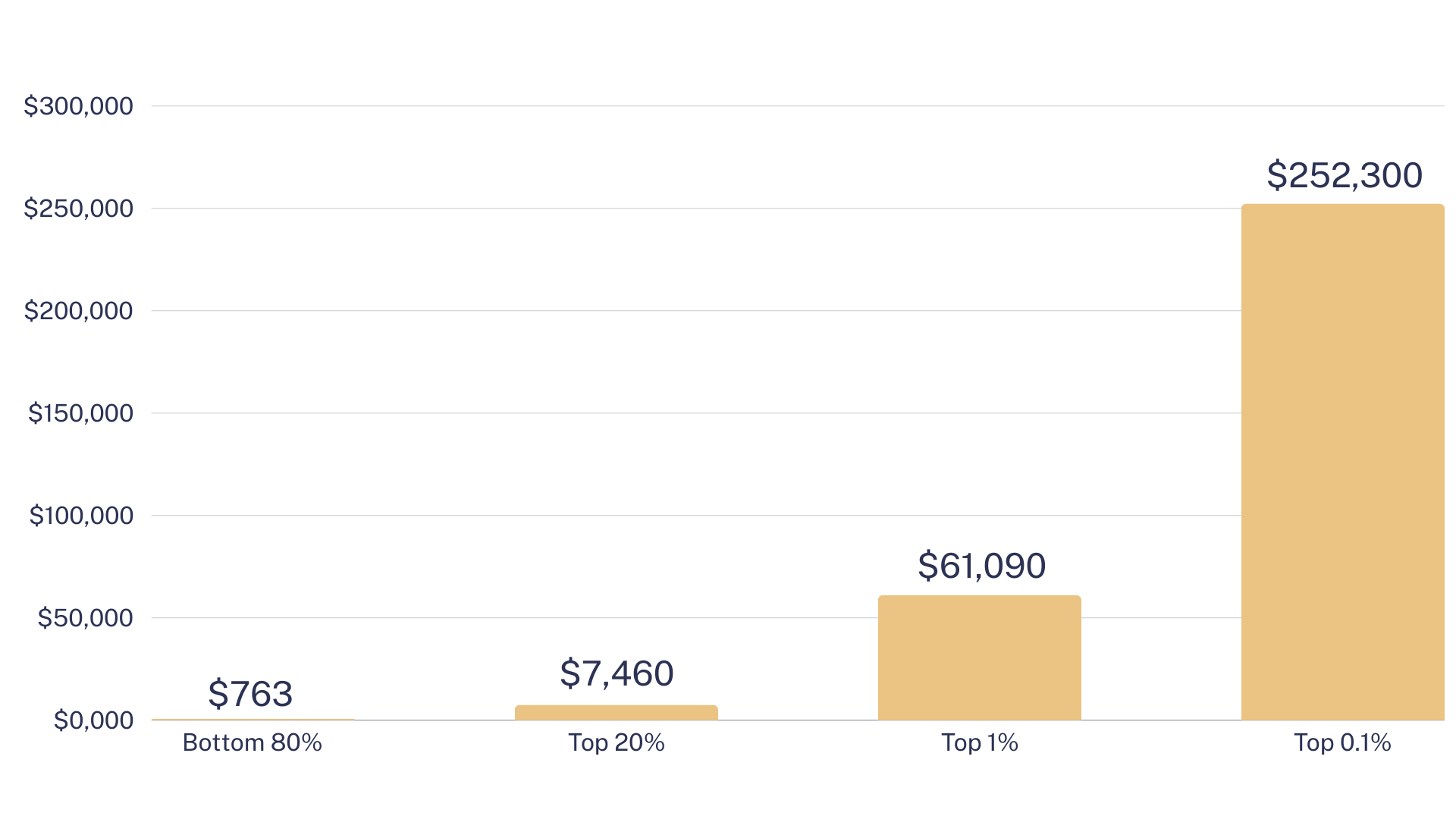

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is a huge giveaway for the wealthy

Annual average tax cut by income group, TCJA, 2025

In 2025, We Can Replace the Failed Tax Cuts & Jobs Act With Tax Policies That Lift Up Families & Communities

The Trump-backed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is exacerbating inequality and wrecking the economy. The TCJA was passed in 2017 by Trump and a Republican-controlled Congress. The largest tax overhaul in three decades, it cut the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, changed how we tax multinational corporations, and temporarily cut personal income and estate taxes, overwhelmingly for the wealthy. In 2025, many of those changes will expire, and Congress will debate the future of these sweeping economic and tax policies.

Far from cutting costs or creating jobs for everyday Americans, the TCJA has been a huge boon to the nation’s richest individuals and most powerful companies, with two of every three dollars in tax benefits going to the top 20% of incomes. The bottom 80% of Americans by income have seen an average tax cut of $763 a year—and many have gotten no tax cut at all—while the top 1% have gotten $60,000, and the top 0.1% have gotten $250,000.

Despite claims from Trump’s own economists that the average American household would see significant annual wage boosts—$4,000 “conservatively,” and up to $9,000 using more optimistic estimates—workers in the bottom 90% of their firm’s income scale experienced no increase in earnings. The vast majority of income gains went to executives who are disproportionately white men. Champions of the TCJA also made specious claims that the corporate tax cuts would “pay for themselves.” Trump’s tax plan costs $2 trillion, adding significantly to the nation’s debt. Even looking at the dynamic effects of the plan—that is, the purported gains to the economy because corporations are paying less in taxes—these corporate giveaways only returned 15 cents for every dollar we invested. In other words, 85% of the cost of the TCJA comes straight out of American communities and bank accounts.

Create Tax Fairness at the Top and Bottom of the Income Ladder

The ultrarich should pay their fair share for the investments that helped build their wealth. Since 2017, the number of billionaires in America has increased from 551 to 748 (a 36% increase), and their wealth has grown by $2.2 trillion (a 77% increase). The nation’s richest 210 individuals hold the same amount of wealth as the entire bottom half, about 165 million people. The wealthiest billionaires pay an average individual tax rate of just 8.2%, compared to 13.3% for the average American.

Not only has the tax code helped the rich get rich, it has also helped them stay and get richer. Because much of the wealth of the ultrarich is gained through increases in the value of stocks, real estate, and other assets they own—rather than income from work—the rich can avoid paying taxes on those assets by never selling them, and instead borrowing against them to get access to capital and then allowing family members to inherit them when they die. This buy-borrow-die strategy is legal and allows the ultrawealthy to avoid paying taxes altogether, or pay a much lower rate than everyday Americans.

These tax preferences overwhelmingly disproportionately benefit white people, who have benefitted from decades of advantages in tax and other economic policies and have therefore accumulated significantly more wealth than people of color. Instead of perpetuating income and wealth inequality and racial disparities, Congress can design tax policies that raise more revenue from the ultrawealthy while exempting working families from tax increases.

Fund the IRS to ensure everybody pays the taxes they owe. Unlike a household budget, the U.S. government sets its own income by raising or cutting taxes. It also decides who pays the taxes that fund our shared investments: businesses or individuals, the rich or the poor. And it must, in all cases, collect the revenue it raises. Individual income taxes make up half of the revenue our government uses to fund community investments, and IRS enforcement is critical to ensuring those taxes are collected. While Republicans in Congress clamor for more cuts to the IRS, each dollar that Congress cuts in IRS funding results in nearly a dollar added to the national deficit. Until the IRA was passed in 2022, the IRS had scarce resources to go after wealthy tax cheats and instead focused their limited resources on disproportionately auditing low-income EITC recipients. With IRA funding, the IRS has been able to focus its collection efforts on high-income households and has recovered $1.3 billion from high-income, high-wealth households in the last two years alone.

End the preferential tax rate for capital gains. Capital gains are the value or profit that an asset gains over time, e.g., the increase in value of a stock in a booming company or of an investment property over time. Capital gains, like all wealth, are highly concentrated among wealthy, white households. As described above, these assets and their profits generate the lion’s share of income for the ultrawealthy. Many capital gains are never taxed at all, but even when they are, they are taxed at a rate much lower than ordinary income like wages: capital gains are taxed at 23.8% for the highest-income households, while work income is taxed at 37%. These tax breaks for the wealthy cost taxpayers $116 billion a year.

Close the tax break on unrealized capital gains. Right now, the ultrarich fund their lifestyles primarily through assets like stocks, not ordinary wage income. Among families worth more than $30 million in assets, 43% of their wealth is held in unrealized capital gains. Since the federal tax code only taxes those assets when they are sold (or otherwise realized), the rich avoid taxes by never selling and instead borrowing against their assets at very low interest rates. This treatment isn’t available to middle-class families: everyday Americans are commonly taxed on unrealized gains, for example, on the increased value of their homes when their homes are reassessed and property taxes go up, or on mandatory distributions from their retirement savings. A “mark-to-market” system would impose a tax on high-wealth families each year based on how much their assets increased in value.

Close the stepped-up basis loophole. The stepped-up basis break allows wealthy families to avoid paying taxes on asset growth over a person’s lifetime once they die and pass it on to an heir. Instead of taxing the gain in value, the tax code “steps up” or resets the baseline value of the asset to its value when the person dies, essentially ignoring any gain in value during the decedent’s lifetime, so neither the decedent nor the heir pays taxes on the gains.

Eliminate or redesign the tax break for pass-through income. Pass-through businesses like sole proprietorships, partnerships, LLCs, and S corporations, are not subject to the corporate tax. Instead, their profits are “passed through” to the owners, who then pay individual income taxes on their share of the profits. However, the pass-through deduction allows filers to deduct 20% of their qualified business income (QBI), effectively lowering their top rate from the ordinary income top tax rate of 37% to 29.6%. This tax break costs about $50 billion a year and is heavily skewed to the rich. Despite comprising only 3% of claims, those with AGI above $1 million reap 46% of the total benefits—frequently gaming the system to maximize pass-through profits. A more inclusive, pro-growth policy would be to explore progressive, bottom-up deductions to give small businesses and new market entrants a fair shot at competing.

There is no shortage of ideas to increase the revenue raised from the ultrarich. For example, to directly tax very high incomes, Congress could impose a surtax on income above a certain threshold, eliminate the carried-interest loophole that allows private equity fund managers to treat their labor income as capital gains, taxed at a lower rate, and require high-income households to pay Social Security taxes on all of their income. To target wealth held over generations, Congress could impose a wealth tax on ultrawealthy households and lower the exemption from the estate tax, which has been so weakened in the last 20 years that it affects almost no taxpayers today.

Refundable tax credits are one of the most efficient ways to cut taxes for working families. The Child Tax Credit (CTC) and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) have long histories of boosting the incomes of low- and middle-income families by providing them with much-needed cash. These targeted tax breaks are the kinds of smart economic policies that put money into the bank accounts of individuals and families who spend it, boosting local economies and helping small businesses. The CTC and EITC also have the potential to narrow racial disparities created by generations of unequal access to economic opportunity. Research shows that these tax credits pay for themselves: generating $10 for every $1 invested in lifetime and economic benefits, slashing child poverty, creating private-sector jobs, and making it easier for parents to work or start new businesses. Any tax agreement in 2025 must include a fully refundable, monthly CTC available to all low- and middle-income families—including a boost during a baby’s first year, as proposed by Vice President Harris—and a strengthened EITC to help workers without children.