In the Media

FAST COMPANY: From childcare to broadband, public options could reshape the U.S. economy and break corporate strangleholds

05. 15. 2024

Consumers want more options. The government should oblige.

This op-ed was originally published by Fast Company.

By now, there’s an economic story that should be familiar to most Americans: Company A begins as a humble startup, offering goods and services whose convenience and price attract consumers. Soon, Company A becomes a Corporation, buying out its competitors, shuttering small businesses, and consolidating its power.

When the Corporation becomes the only game in town, consumers are left with little choice, while the Corporation has nothing but choices: how high to set its prices, where to hire the cheapest labor, what quality product is an acceptable bare minimum, all in service of generating the highest profit.

We’re seeing this play out in the 2020s, after decades of corporate deregulation and market consolidation that started in the 1970s. But it was the same story in the 1920s—a time when the market consolidation created by the “trust” system built corrupt robber barons. Gradually, consumer sentiment shifted and politicians began pushing back, calling for public reforms and regulations and seeking to rebalance the market. The unbridled consolidation and power of the 1920s was mostly halted once President Franklin Roosevelt’s progressive reforms kicked in.

This series of public investments coupled with a strong anti-monopoly framework led to unprecedented economic growth, innovation, and American prosperity from 1936 until the deregulation push of the 1970s and ’80s. The key factor of its success was how the New Deal made public works a cornerstone of these investments, creating entities like the Public Works Administration to build public parks, roads, bridges, and schools, and the Tennessee Valley Authority to create a federally-owned electric utility corporation.

Those public options created through public investments helped us reimagine what was economically possible. Already, public options are a big part of our lives: public education gives students access to quality schooling, the U.S. post office co-exists with companies like UPS and FedEx, public libraries open up knowledge, and public parks create free green space and playgrounds for everyone. The opportunity to grow public options—for instance, for child care or for prescription drugs like insulin—gives more agency to consumers who are feeling the crunch of few good options that also fit their budget.

Today, we’re rediscovering the possibility and promise of that market shaping-approach after four decades of deregulation and market consolidation. The federal government rolled out $4 trillion in investments through a combination of the Inflation Reduction Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, the American Rescue Plan Act, and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, a striking mandate. Channeling this investment to people and communities, instead of being co-opted by private actors waiting in the wings, can happen by deploying the public options framework our nation has used so successfully in the past.

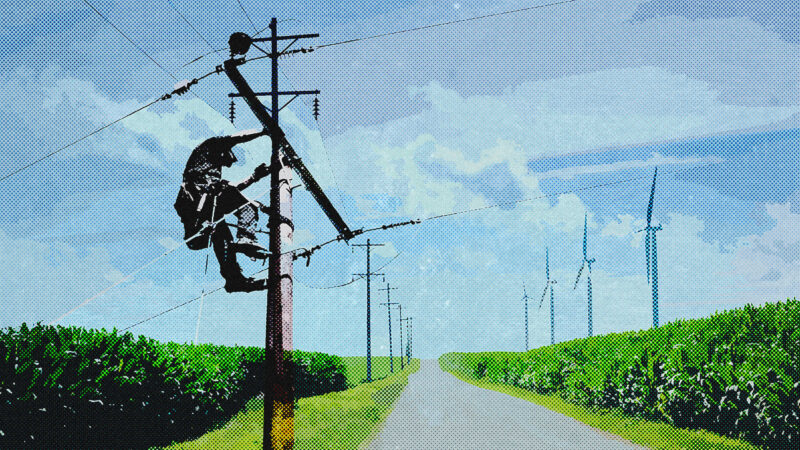

Take the example of providing high speed internet and electricity to areas that currently lack infrastructure and access. When public options are in the mix, their design is centered on how to improve products or services for people. Because they’re not chasing short-term profits, public options end up creating competition and diversity in the market as a result. A public option for high-speed internet in Chattanooga, Tennessee, established a fast and reliable broadband network with public leadership and funding, becoming a national leader in internet speed and access, and generating broad economic benefits along with it.

The program provides a blueprint for the kind of impacts a public option for broadband could have on people. Chattanooga’s Electric Power Board (EPB)—a publicly owned enterprise created in 1935 that operates under the oversight of a five-member board appointed by Chattanooga’s mayor—has accountability baked into its governance structure, leading to a stable and continuous expansion of broadband services that now reaches to 70% of of the city’s electricity users. This accountability means a more tailored approach to troubleshooting when a problem does arise, and better service overall. As a result, the EPB offers competitive pricing while maintaining—and in fact, improving—quality of service.

More recently, the federal Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment program (BEAD) is seeking to do more of what the EPB did in Chattanooga. Launched in 2021, BEAD endeavors to give all Americans access to fast, reliable broadband, with states leading the way on creating tailored maps of unserved areas and developing plans for the funding they receive. In an era of remote work and remote learning, internet access is a vital public service—the BEAD program makes strides in guaranteeing that more Americans can access it.

In stark contrast, private options for goods and services often center profits and returns on investment. Though there’s a valid business case for this, not having public options to create competition in the market can end up exacerbating the existing problems of consolidation and monopolization, both of which lead to fewer choices for consumers. In everything from air travel (only four major U.S. airlines remain) to cell phone services (three main providers), consumers are faced with shrinking choices in private marketplaces.

Particularly concerning are examples like Duke Energy in North Carolina, where the utility’s legal monopoly status grants it unchecked control over electricity prices. Similarly, Georgia Power’s monopolistic hold in the state is deepening racial injustice through “unequal access to affordable electricity.”

In Maine, consumers sought to wrest control of their utilities back from the two power companies holding monopoly power in the state. Though the ballot measure failed in November, supporters continue building public awareness of the monopoly’s impacts on everything from slow-response times to storm-related outages to barriers in connecting renewable energy sources to the grid.

Economists, pollsters, and journalists alike have sought to make sense of the disconnect between one of the strongest economies in recent memory and negative sentiment from the American public. But while policymakers focus on present-day conditions, they fail to zoom out. What many Americans feel today—described as the “vibecession”—is likely the cumulative impact of dwindling consumer choices; increased monopolization, privatization, and consolidation in the marketplace; and fewer affordable, quality alternatives. They sense that they’re living with the “illusion of choice,” personified by the high prices of everything from groceries to prescription drugs, and characterized by shuttered small businesses and decimated local main streets.

Public options have historically chipped away at monopolies’ strongholds. When FDR pushed for public power to curb exorbitant prices, he brought electricity to rural communities and moved the nation into a new era of prosperity.

As we enter a pivotal year with so much hanging in the balance, more than just our economy is at stake. This new wave of federal investments wields much in its ability to shape our society for the coming decades. Public options can drive a more just and equitable capitalism driven by democracy, rather than one driven by a plutocracy. America has done it before, to great economic success. We’re poised, at this moment, to do it again.